Spats in the Straits Between Mayalsia and Singapore

[By Dr. Bec Strating]

While the South China Sea is a high-profile example of complex maritime and territorial disputes in the Indo-Pacific, there are other disputes that get less attention, yet also potentially undermine, the UNCLOS-based efforts to maintain maritime order.

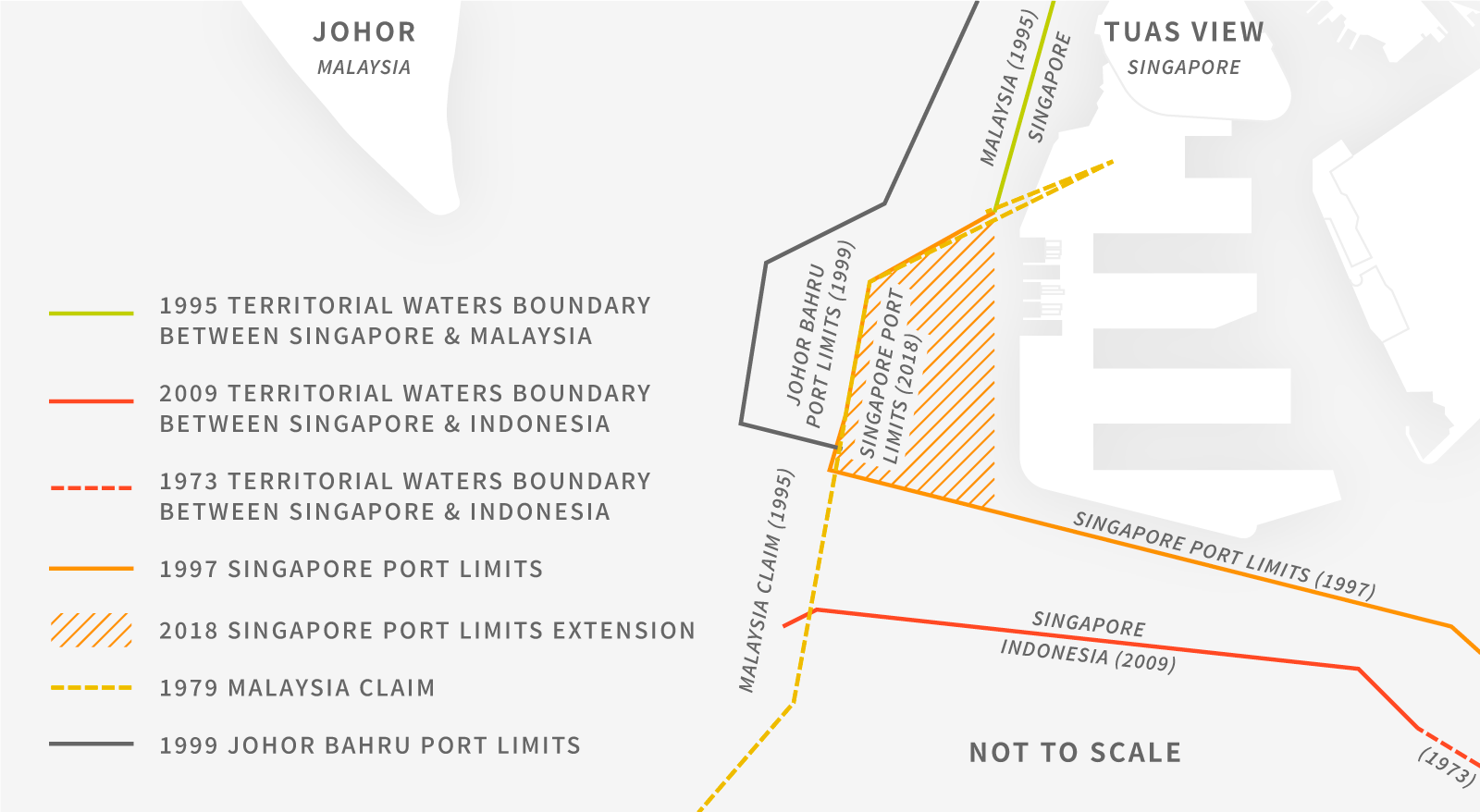

One such dispute exists between Singapore and Malaysia, which (re)emerged unexpectedly in October last year. This dispute concerns the maritime area in the Johor Strait, which is off the coast of Singapore’s reclaimed land area known as Tuas.

On October 25, Malaysia issued a gazette notice that stating its intention to extend its Johor Bahru port limits into Singapore’s territorial waters. Port limits are those boundaries where seaport activities occur. The limits usually conform to territorial waters.

Safeguarding sovereignty

On November 5, Singapore responded in protest, requesting that Malaysia confirm Singapore’s sovereignty of its territorial waters. Instead, Malaysia issued a port circular to notify the shipping community of altered limits on November 11. A diplomatic tit-for-tat ensued across for the following two months.

Singapore also extended its port limits to the full extent of its territorial waters on December 6, creating a contested area that signifies overlapping port limit claims.

Contested port limits in the Johor Strait (Source: Malaysian Ministry of Transport)

Both sides invoked sovereignty to defend their claims. Singapore’s government describedMalaysia’s move as encroaching “Singapore’s territorial waters off Tuas”. Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat claimed Malaysia’s move was a violation of international law. Other Singaporean ministers accused Malaysian government vessels of intruding its territorial waters.

In return, Malaysia Transport Minister Anthony Loke declared that “the altered port limits of Johor Bahru are in Malaysia’s territorial sea and it is well within Malaysia’s right to draw any port limit in our territorial sea in accordance with our national laws.” According to Loke, the act of land reclamation involved with Tuas amounted to “serious violations of Malaysia’s sovereignty and international law and are unconducive to good bilateral relations”.

Along with maritime issues, airspace has also been contentious, with Malaysia protesting the proposed use of a new Instrument Landing System (ILS) at the Seletar airport, arguing that flight paths would restrict development in the Johor town of Pasir Gudang. In response, Singapore has argued that it would rely upon existing flight paths that have been used for decades.

Vexed history

The dispute should be understood in its broader historical context. In 1979, Malaysia mapped its sea territory, provoking protests from Singapore. In 1995, Malaysia and Singapore agreed upon (most of) a maritime boundary in the Johor Strait. In 1999, Malaysia published its amended Johor Bahru port limits, which corresponded to the territorial sea limits claimed in its 1979 map. The new moves extend the port limits beyond Malaysia’s 1979 territorial claim.

Singapore’s extensive land reclamation activities have long been a source of anxiety for its ASEAN neighbour. Kuala Lumpur has argued the reclamation impinges upon its territorial waters. In July 2003, it took Singapore to the International Tribunal for the BahLaw of the Sea (ITLOS) in an unsuccessful attempt to provisionally halt Singapore’s reclamation projects, including Tuas.

Another key maritime and territorial issue has been the ownership of Pedra Branca – a small island located at the eastern entrance of the Straits of Singapore – as well as two maritime features, Middle Rocks and South Ledge, a low-tide elevation. In 2008, the International Court of Justice awarded Singapore sovereignty of Pedra Branca. Malaysia filed an application to have the case reopened on the basis of new historical records, however, this last-ditch effort was abandoned in 2018.

Regional consequences

After a meeting of foreign ministers in January, a temporary détente on airspace issues was established. Both countries made concessions: Malaysia suspended its permanent restricted area in airspace Pasir Gudang, while Singapore suspended the planned implementation of ILS for one month.

The maritime disputes signal a potential return of tense relations between the ASEAN neighbours.

Some commentators have noted that these disputes have intensified since the return of Mahathir Mohamed as Malaysia’s prime minister in May 2018. The disputes are a reminder of the tense relations between the two countries during his first term (1981-2003).

In parliament, Singapore’s Foreign Minister, Vivian Balakrishnan, stated that Singapore is not afraid to use “sharp elbows” to defend its national interests. He also suggested it was unlikely that the spat would be over soon. Even after the airspace concessions, Singapore cancelled a meeting to discuss joint border developments in protest against Johor’s Chief Minister, Osman Sapian, for posting a photo on Facebook of himself aboard a Malaysian vessel in Singaporean waters the day after the foreign ministers met.

Beyond the bilateral, there are potential regional implications. One of the motivating factors in Indo-Pacific maritime disputes is the protection of claimed territorial sovereignty. This is no different in the Singapore and Malaysia maritime dispute. The nationalisation of maritime disputes makes them increasingly difficult to resolve.

Second, this is an intra-ASEAN dispute that comes at a time when the regional association needs to develop a unified front as it works towards a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea with China.

Third, both sides argue that international law is on their side, raising questions about the capacity of UNCLOS to help resolve the dispute. Singapore and Malaysia in the past have used both ITLOS and the ICJ to assist them in finding solutions to maritime and territorial disputes. Will they find a solution? It will depend on each country’s judgement of the value of a “rules-based order”.

Dr. Bec Strating is a lecturer in politics at La Trobe University, focusing primarily on Timor-Leste and Indonesia.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter, and it may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.