What We Are Getting Wrong About the Indian Ocean

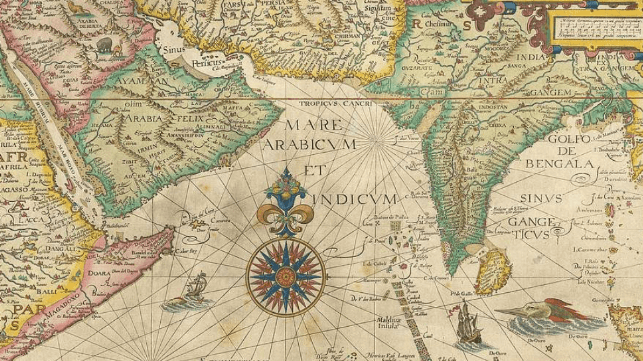

Recent studies in geopolitics appear to concur that the Indian Ocean rim could become the world’s most important economic region, surpassing the Pacific Rim. Indeed, the competition amongst global super powers for control of the Indian Ocean and its resources has intensified.

An important trade route for centuries, the Indian Ocean now commands major sea-lanes where half of the world’s container ships pass, as well as 70 percent of the world’s oil shipments. It is a critical resource for the region’s littoral states, as well as outside powers.

However, as more countries scramble for a share, some blind spots in the geography and the key regional players have emerged. This hinders the ability to assess the region’s importance to global competition.

“The Indian Ocean is often split among the South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern regions, but these artificial divisions emphasize the landmasses and push the maritime domain to the periphery. Further, they move the concerns and priorities of island nations, which otherwise would act as important regional players, under the challenges of their continental counterparts,” observed Darshanah Baruah and Caroline Duckworth, marking the launch of a new interactive map by the Carnegie Endowment aimed at modernizing the understanding of the region.[1]

To fully monitor and absorb key developments in this strategic maritime domain, the Indian Ocean must be viewed as a single region, argue Baruah and Duckworth.

For instance, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are considered part of South Asia, while Mauritius and Seychelles are considered part of Africa. Though these regional divisions suggest these nations have major differences in economic goals and security needs, they are united on issues of climate change, the importance of multilateralism and pursuit of promoting blue economy.

In addition, four key points arise when Baruah and Duckworth view the Indian Ocean holistically.

First, although the Indian Ocean is known to have three chokepoints - the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb – the Mozambique channel has emerged as a critical backup trading route. This was visible during the blockage of the Suez Canal in 2021, when some ships re-routed around the Cape of Good Hope and through Mozambique Channel.

These chokepoints provide a strategic military advantage to any regional player that gains their control. If a single nation gets the power to keep these sea lines of communication (SLOC) open during peacetime, it also has power to close them during times of conflict.

Take the case of the Strait of Hormuz, where approximately 21 million barrels of oil pass each day, according to estimates by the U.S Energy Information Administration (EIA). Even a slight event along this route can affect global energy supply and trade.

Second, while China is considered a primary trading partner for Indian Ocean’s island nations, their trade with the UAE (United Arab Emirates) frequently surpasses that of China, India and the U.S. Further, Qatar and Turkey are emerging as new players in this trade dynamic, gradually replacing the European and African countries that have been the historical trade partners.

Third, the Indian Ocean’s fifteen ongoing territorial disputes highlight the region’s complicated colonial legacy. Some of the notable unresolved issues include France’s multiple disputes with Comoros and Madagascar, and the protracted dispute between the United Kingdom and Mauritius over the Chagos Islands.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

“These sovereignty disputes with the West open the door for islands to deepen their relationship with China. While assertive in the South China Sea, China has no territorial disputes in the Indian Ocean region, seeking instead to balance the western influence,” note Baruah and Duckworth.

Finally, in viewing the Indian Ocean as a single theater, France, India and Australia have an overarching regional role. By virtue of having territorial islands in the Indian Ocean, their military and trade security objectives intersect. Hence the need for a harmonized strategy, implemented collaboratively through the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA).

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.