The Strategic Consequence of the Diego Garcia Dispute

[By Dr. Bec Strating]

At the end of last month, the African archipelago nation of Mauritius secured an important legal victory in its territorial and maritime disputes against its former coloniser, the United Kingdom.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) produce an advisory opinion that rejected the UK’s claims to sovereignty over the Chagos Islands, a small group of atolls in the Indian Ocean. It found instead that the UK had unlawfully separated the islands from the former colony of Mauritius, and that the UK should cede control “as rapidly as possible”.

The advisory opinion emerged after Mauritius successfully petitioned the United Nations General Assembly to ask the ICJ to produce an advisory opinion on the determination of the islanders (the “Chagossians”) in 2017.

Both the petition and the advisory opinion were widely viewed as a blow against the last vestiges of British colonialism in Africa. The UK’s denial of Chagossian self-determination has damaged its international reputation at a time when it is struggling to fulfil its own independence by leaving the European Union, as well as defend the “rules-based” international system.

A “pressured” agreement and geo-strategic importance

Mauritius had been engaged in a long-term struggle to reclaim Chagos Islands from the UK. The islands fell under British control in the 19th century and were administered under the colony of Mauritius. In contrast to the legal principle of uti possidetis – in which European colonial borders determined the boundaries of new, independent sovereign states – the UK planned to separate Chagos from Mauritius in the 1960s. While an “agreement” with Mauritius was struck in 1965 that the Chagos Islands would remain part of “British Indian Overseas Territory” (BIOT), the Mauritians claimed they had no choice and had been pressured into the agreement.

While Chagos Islands was a non-self-governing territory, it never made it on the 1960 UN Declaration on Decolonisation list, which would have entitled it to a process of self-determination under international law.

From 1967–1973, the UK forcibly moved around 1500 Chagossians to Mauritius and Seychelles, and/or prevented them from returning. This dispossession was contrary to international law. Articles 9 and 13(2) of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, for example, respectively state “no one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile” and “everyone has the right to leave any country including his own and to return to his country” (emphasis added). In 2002 and 2006, reports by the UN Human Rights Committee determined that the exile of the Chagossians was unlawful.

Britain argued that compensation in 1982 had resolved the issue and that a process of decolonisation had been completed. Closer to Australia’s neighbourhood, this is reminiscent of arguments employed by Indonesia in East Timor and West Papua, in which coercive, sham processes were (and in West Papua’s case, continue to be) employed to counter self-determination arguments.

There are strategic and material reasons why the UK is keen to hold onto Chagos Islands. They have geo-strategic importance, as the UK leased out the biggest island – Diego Garcia – to the US for a Cold War-era military base.

The UK also sought to claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and Marine Protected Area (MPA) around the Chagos Islands.

A challenge to the marine claims

In 2011, the UK government attempts to create an MPA were subject to an arbitral tribunal case initiated by Mauritius and constituted under Annex VII of the United Nations Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The dispute primarily concerned the legality of UK’s MPA under the convention in the context of ongoing disputes over sovereignty, and as such constitutes a “mixed dispute” involving concurrent unresolved land sovereignty issues and maritime entitlement issues.

The MPA extended over a distance of 200 nautical miles, covering an area of more than half a million square kilometres. Mauritius argued that the UK was not entitled to declare an MPA or other maritime zones because it was not a “coastal state” for the purposes of law of the sea – that is, not legally sovereign over the Chagos Islands. It also argued that the MPA infringed the fishing entitlements of Mauritius, and that its purpose was to block the Chagossians from returning to the islands in violation of international law.

According to the UK, the proceedings were “artificial and baseless” and it asserted that it held sovereignty over the islands (as well as maritime entitlements) permitted to coastal states under the convention. Ultimately, the arbitral tribunal concluded that the declaration of the MPA was not in accordance with the provisions of UNCLOS.

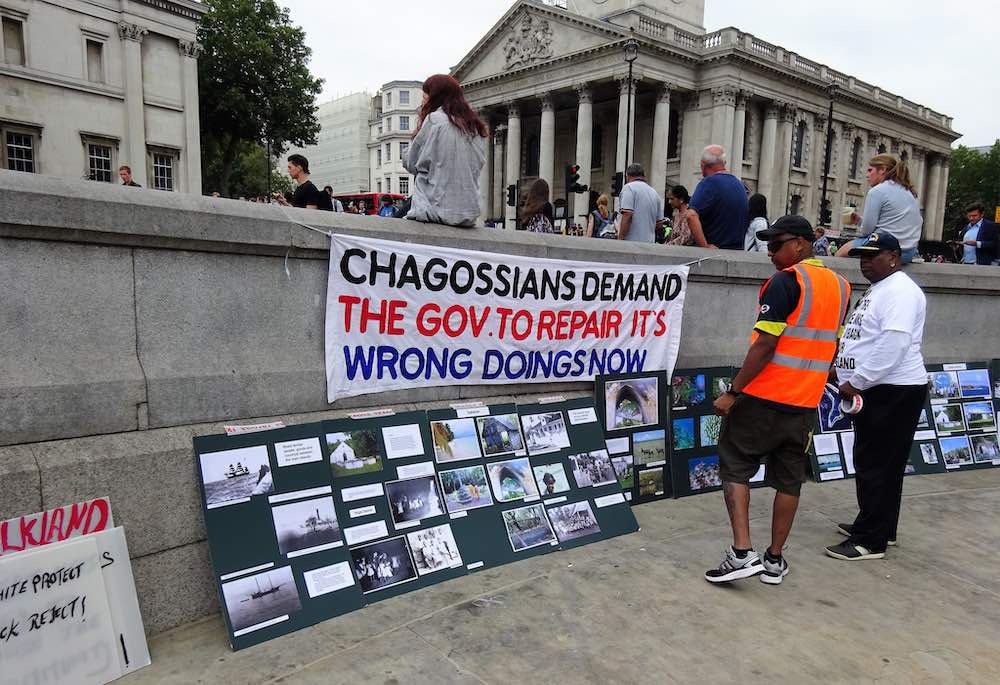

A demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London, over the Chagos Islands, July 2018 (Photo: David Holt/Flickr)

Why do these disputes matter?

As UK officials argue, the ICJ opinion on self-determination is only advisory. Nevertheless, the opinion from the court does serve to increase the international pressure on the UK to hand back sovereignty of the islands to Mauritius, even if, according to the UK Foreign Office, that threatens the role of the Chagos Islands in the UK and US defence in the Indo-Pacific. Unsurprisingly, the US supported the position of the UK.

Importantly, the ruling comes at a time when the Royal British Navy has begun conducting freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea. These operations are designed to challenge the illegality of China’s assertive island building and excessive maritime claims. Yet, the UK’s ongoing defence of its illegal possession undermines its credibility as it simultaneously seeks to defend the “rules-based international system” in maritime domains.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

In a time of great power contestation, the lack of consistent application in the international rule of law by non-great powers, such as the UK, ultimately weakens the capacities of the UNCLOS-led legal regime to establish maritime order.

Dr Bec Strating is a lecturer in politics at La Trobe University, focusing primarily on Timor-Leste and Indonesia.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.