The Navy's Future Drone Fleet Needs Better Satcom Coverage

[By Brandon Walls and Nicholas Ayrton]

As times change, they demand that military doctrine and strategy change with it. Key to this is ensuring that the American military is ready to act anywhere and with short notice, requiring that it embrace the latest technologies to overcome the latest operational problems. From the Reaper drones of the American wars in the Middle East to the Azeri drones that came to define the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, land-based drones are rapidly shaping the battlefields of the modern world. But the maritime domain has yet to fully embrace the use of drone technology.

The area of maritime drones seems to be a field where the civilian sector is more rapidly embracing new technology compared to the military. Norwegian company Kongsberg Maritime has recently concluded initial tests of an unmanned cargo container ship, making its first delivery to a fertilizer company, while South Korean technology giant Samsung is also investigating crewless vessels as a means to cut down on labor and maintenance costs to better stand against its Chinese competitors. It is in this second area of potential for advancements in cost-cutting and smaller crew requirements that the United States Navy (USN) could benefit most due to the increasing problem of an aging fleet of transport ships in need of replacement, as well as a personnel shortage that has only gotten more dire with time.

Unmanned Solutions to Logistics Problems

The dire state of naval logistics is hardly anything new, with General Stephen Lyons, current head of USTRANSCOM having said that in the event of a major conflict, there would not presently be sufficient naval sealift capacity to supply the United States military. Indeed, the capacity of the Navy is presently stretched so thin that, by its own admission, it would be unable to defend the military’s maritime supply lines in the event of a large-scale conflict. This is compounded by the nearly obsolete ships that are still in service and declining in numbers. In addition to this, the USN has been facing an ongoing shortage of sailors, falling several thousand below its targeted number year after year. This has led only to more problems, as currently serving sailors are then forced to pull extra weight, leading to overworking, lack of rest, and a generally less effective fighting force. In this area, one then finds a maritime logistics force in need of a modernization effort, coupled with a Navy that needs to either find more recruits or cut down on the number of jobs it needs sailors to fill.

Here unmanned maritime vessels offer a solution, allowing for the logistics ships of tomorrow to be built more cheaply and not requiring bulky spaces for crew compartments, food, water, and other aspects. More efficient designs could better fulfill their mission of carrying supplies where they need to go. Further, if naval logistics could be rendered more autonomous, this would theoretically allow for a much smaller number of sailors to command a much larger fleet of supply vessels, perhaps permitting a single sailor to monitor several largely autonomous ships, with direct control being needed only in particularly critical moments.

While the USN does appear to be looking into autonomous vessels, the focus seems to be on relatively small vessels, only around the size of a corvette, not on the large logistics vessels that would seem to be the most well-suited for automation and heavily demanded in sustained conflicts. While tests with these vessels have been promising, being able to operate without human intervention for all but the most delicate phases of their missions, the Navy’s program still lacks the ambition needed to truly capitalize on the potential for an unmanned naval logistics force. It is currently focusing more on small, rapid-response supply vessels, while continuing to neglect the larger vessels that would be needed for a large-scale conflict.

Starlink and Commanding Drone Fleets

Extending beyond logistics, there also exists the potential for maritime drones and unmanned ships to be more involved in the observational and informational sides of warfare. Indeed, if admittedly biased sources out of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are to be believed, then the U.S. is already making limited use of maritime intelligence drones, with one having supposedly been captured while operating off the coast of Jiangsu province to the north of Shanghai. If this is to be believed, then it offers the possibility of further using small, risk-worthy maritime drones to conduct surveillance, such as for general intelligence gathering or targeting for fires. A small fleet of semi-autonomous drones could also act as a screening force for operations, acting to provide an extended sensor net and provide greater tactical awareness, be they for combat operations or as an early warning system for unescorted logistics fleets.

However, with these hypothetical drone systems, whether in the form of logistics vessels, intelligence gatherers, or as a sensor net, there still exists the crucial question of establishing a reliable method of controlling them, since even an otherwise autonomous vessel may encounter a situation where a human operator must provide input. Current military communication satellites, while advanced, are also chronically overburdened and fighting for bandwidth with what little is available having to be rationed out to only the most crucial of systems and operations.

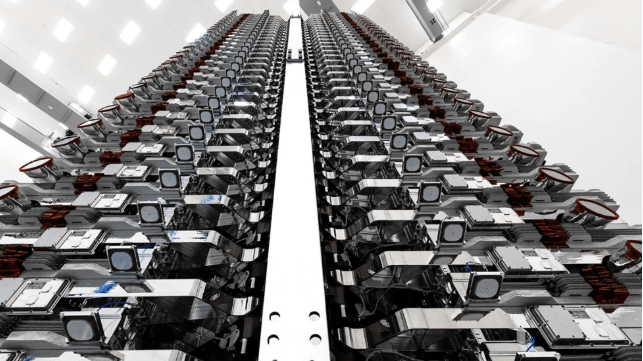

Enter Starlink. SpaceX’s new Starlink satellite constellation provides many options for military communications, provided the network could be rendered secure enough. The Starlink constellation currently consists of over 1,600 satellites, with plans to have thousands more of the mass-produced small satellites in low Earth orbit in the coming years. If successful, such a program would be theoretically able to provide easy and reliable connectivity for a globally-operated network of maritime drones that could be set up with only minimal infrastructure, allowing for large numbers of these units to be commanded.

The main issues are testing if the basic premise could function and if the system could be rendered secure. The first issue is whether a commercial system currently designed to provide connectivity to a variety of static locations could work as a command-and-control network for a fleet of autonomous vessels traversing the world’s oceans. Similarly, the United States Air Force has already begun the process of testing if Starlink technologies could function onboard a moving aircraft, likely a far more difficult task than connecting a relatively slow-moving ship onto which one could fit a larger array of communications equipment.

Secondly, concerns have been raised about the security of Starlink for military applications, as the network relies on communication with several ground-based hubs to function, while the military tends to prefer direct satellite-to-satellite optical communications. However, this too seems to be a solvable problem, with ten Starlink satellites with intra-network communications capability having been launched into a polar orbit this past January. Indeed, SpaceX has recently confirmed that all future Starlink satellites will be launched with the capability to use laser communication systems between satellites. If SpaceX could successfully work with the Defense Department, it could be feasible to bring the network’s security up to the standards needed to coordinate a fleet of maritime drones.

Conclusion

It is these two emerging technologies, maritime drone vessels and large satellite communication constellations, that could allow for the Navy to solve some of its ongoing issues and permit the creation of a more nimble, lean, and modern force able to better confront the rising security threats facing the United States in the years and decades to come.

Brandon Walls is an undergraduate student at the University of California, Davis.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Nicholas Ayrton is a U.S. Navy veteran and current undergraduate student at the University of Arkansas.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.