Digital Collaboration in Chemical Logistics

Decarbonization Is Turning Transport into a Chemical Logistics Coordination Challenge

[By Mikael Lind, Wolfgang Lehmacher, Jeremy Bentham, Chye Poh Chua, Philippe Isler, Jens Lund-Nielsen, and Per Löfbom]

Transport still relies heavily on fossil fuels and accounts for roughly one quarter of global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. Shifting this energy base to sustainable alternatives requires a systemic effort. As transport decarbonizes, the way fuels are supplied changes fundamentally. Crude oil and derived refined products are handled through mature infrastructure and well-established operating practices. In contrast, many low-carbon energy carriers fall outside this model as clean energy infrastructure remains materials-intensive and relies on polymers, composites, specialty gases, electrolytes, solvents, and coatings supplied by the chemical industry.

Hydrogen carriers, synthetic fuels, advanced biofuels, and e-fuels are produced, stored, and transported as chemical products that are contamination-sensitive, hazardous, and tightly linked to plant and storage operations. As with traditional fuels, moving them safely and efficiently typically requires specialized terminals, strict tank cleaning routines, careful sequencing, and close coordination among ships, storage, and inland transport.

Maritime transport accounts for most of global trade by volume. It remains the backbone of world trade, with energy commodities such as crude oil, petroleum products, LNG (liquid natural gas), and LPG (liquid petroleum gas), accounting for the bulk of tanker capacity. Transition outlooks foresee part of this trade shifting toward chemically derived fuels such as methanol, ammonia, synthetic fuels, and advanced biofuels, which will largely move through existing ports, terminals, and ships serving the chemicals industry. Long-term decarbonization perspectives similarly point to low- and zero-carbon fuels supplying a growing share of shipping energy demand from a low base, often via regional hubs and corridors where these fuels move as chemical cargoes.

The challenge is therefore not only how to produce low-carbon fuels, but how to coordinate their movement reliably across complex, multi-actor chemical supply chains, and expand the use of more selectively applied just-in-time practices to the entire end-to-end supply chain.

The Industry Is Optimized, but Lags End-to-End Coordination

Chemical logistics has been optimized within companies: shipping lines use advanced scheduling tools, terminals adhere to strict safety and quality standards, and producers manage production, storage, and deliveries with digital support. The main weakness lies in both fragmentation and coordination between organizations, where small differences in readiness, sequencing, or arrival times trigger last-minute changes to berth plans, tank assignments, and inland transport, necessitating buffers and emergency responses.

In a decarbonizing transport system that relies on tightly linked fuel and material flows, these coordination gaps increase costs, risks, and the likelihood of delays in scaling low-carbon solutions. The challenge is evident in liquid bulk, where tankers carry multiple chemicals in separate, compatibility-constrained tanks and terminals handle diverse, safety-sensitive products; when arrival times shift, tank planning, inland transport, and sometimes production must all be adjusted.

Chemical Logistics and the Business Logic of Dependency

Chemical logistics is structurally tight: many storage tanks are product-specific and integrated into production, blending, and safety systems, and many sites operate near capacity, leaving little room for error and disruption. Experts estimate logistics costs at 15–25% of product value, so delays and misalignment quickly erode margins, and even modest improvements in supply chain coordination unlock meaningful value and resilience.

In this environment, uncertainty is more damaging than delay: predictable lateness can be planned around, whereas uncertain arrivals force actors to hold extra inventory, reserve capacity “just in case”, and pay for back-up options. Operational experience across the chemical and liquid bulk chains shows that minor deviations early in the chain can materially degrade routing and sequencing efficiency, with knock-on effects on fleet use and plant performance. In this industry, commercial sensitivity is intrinsic, since data on readiness, sequencing, or prioritization can reveal production status, customer exposure, or market position, particularly in competitive tanker markets, so any coordination model must accept limited, selective information sharing.

Why Traditional Digital Coordination Models Fall Short

Many digital collaboration initiatives assume either a central orchestrator or a broad willingness to share detailed information, neither of which aligns with the realities of the supply chain industry, including chemical logistics. In liquid bulk, port authorities manage safety, access, and traffic, but not commercial supply chains; terminal operators act on behalf of cargo owners with only partial visibility; and there is usually no single operator or platform coordinating end-to-end.

Ownership structures reinforce fragmentation as cargo owners may own tanks or captive terminals and hold long-term capacity. Still, they cannot own port authorities, and ports are not natural custodians of commercially sensitive information. Shipping lines face similar constraints: ship positions are visible, but sharing precise arrival plans or onward employment can reveal strategy, making it hard to adopt systems that treat ETA (estimated time of arrival) as a fixed promise. The core issue is not data scarcity but the absence of governance arrangements that allow coordination without over-exposure, a gap that becomes more consequential as decarbonization makes chemical and energy flows more interdependent. This more interdependent future is expected to arrive sooner rather than later in the industry, making adjustments for better coordination in chemical and energy supply chains an urgent matter to protect margins and profits.

The Foundations of End-to-End Digital Collaboration

The key opportunity is to move interventions and activities from late, reactive alignment towards earlier, shared coordination along the end-to-end chains. The energy transition process makes an urgent necessity rather than a “nice to have”. Coordination works best when limited, pre-agreed sets of primary data are shared directly by those closest to the action and the chain of events, including shippers, cargo owners, terminals, shipping lines, and inland operators, rather than relying mainly on estimates derived from third-party data, which do not provide high accuracy and certainty.

In chemical and liquid bulk energy and feedstock flows, a small set of signals is often sufficient: planned, estimated, and actual arrival and departure times at transport nodes along the end-to-end chain, shared at the source and updated as conditions change, enable others to adjust in time. This can be transformative and leads to three design principles: cargo owners decide who sees what, because they control readiness and bear much of the risk; ETAs are treated as intent, updated as conditions evolve, to facilitate early data sharing; and visibility is limited to actors directly involved in a flow, for a defined purpose and time window, to protect commercial interests.

These principles are well-suited to liquid bulk corridors for future fuels and critical intermediates, where tighter coordination is needed without undermining competition or confidentiality.

Principle and Practice: Primary Data with Ports in the Loop

Disturbances in chemical logistics tend to propagate across the full chain - from production sites to terminals, storage facilities, downstream plants, and inland transport. Coordination therefore needs to span the entire end-to-end flow, not just individual nodes. In practice, this points to a cargo-owner-driven, terminal-centred community model with port authorities in the loop. Producers, traders, suppliers, receivers and industrial users, terminal operators, shipping lines (tankers, container carriers, tank-container operators), inland transport providers, forwarders, and port authorities - including customs, safety bureaus, and other regulatory actors - form the core coordination group in chemical logistics. Given the layered nature of chemical value chains, where one actor’s output becomes the next downstream input, these flows often remain seaborne and interconnected across multiple stages and geographies.

Within this group, each participant shares their planned, estimated, and actual arrival and departure times, rather than only the cargo or vehicle's actual position, which usually provides limited value. This enables better sequencing, resource allocation, and contingency planning without revealing sensitive details. Ports and terminals benefit from structured pre-alerts on arrival windows, deviations, and actual movements, improving chain fluidity, safety, and energy transition planning and execution, while the commercial context remains within the individual companies. As analyses of emerging green shipping corridors show, linking short-sea trade lanes such as Sweden–Belgium with deep-sea bulk routes from South Africa to Northwest Europe can create corridor structures where stakeholders coordinate green ammonia production, fuel supply, and transport execution using limited shared signals. Such corridor-based coordination enables actors to absorb production or voyage delays, re-optimize berths, storage tanks, and inland flows, and reduce reliance on emergency storage, spot chartering, and losses of low-carbon fuels, while avoiding the disclosure of commercially sensitive information or counterparties1 (North Sea Port, 2024; Global Maritime Forum, 2025).

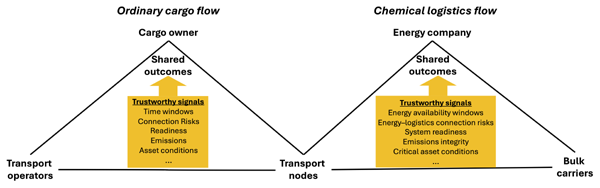

Building on the Trinity approach, the illustration below extends the coordination logic from ordinary cargo transport to a chemical flow transport system. While the same trustworthy signals - time windows, readiness, connection risks, emissions, and asset conditions - continue to sit between cargo owners, transport operators, and transport nodes, they are expanded to reflect energy availability and carbon integrity. In doing so, the model links transport execution directly to sustainable energy supply, ensuring that logistics flows are not only operationally aligned but also powered by verified low-carbon energy, without requiring the exchange of commercial data or contractual positions.

VWT as a Public Good Powered by TWIN

The Virtual Watch Tower (VWT) (www.virtualwatchtower.org) operationalizes this model as an emerging public good service for the global supply chain community rather than a proprietary platform or commercial intermediary. Its role is to provide neutral digital infrastructure for coordination, not to own or monetize data or manage transport flows.

The Trade Worldwide Information Network (TWIN.org) is a distributed system of independently operated nodes, organized in a decentralized (federated) trust architecture. Offering VWT the backbone for controlled, purpose-bound data sharing among a limited set of actors, backing VWT’s digital architecture (VWTnet), allowing data to remain with its owners while selected and limited planning, intent and progress signals are shared under agreed rules. VWT shows that it is possible to coordinate end-to-end flows in commercially sensitive environments without undesirable full transparency or centralized control, making governance - not technology - the main innovation. For liquid bulk chains, using this model at the terminal level can create a light-touch coordination layer across multiple ports, corridors, and value chains without imposing a single commercial orchestrator.

So What for CEOs and Policy Makers?

Senior business and policy decision makers should factor the following considerations into their strategic thinking around liquid bulk chains:

• Supply-security and decarbonization are now coordination problems. Ensuring reliable access to future fuels and critical intermediates depends as much on end-to-end coordination of chemical logistics as on production capacity or shipping technology.

• Governance is the bottleneck, not data or tools. The primary constraint is the lack of trusted frameworks for sharing minimal yet critical data signals among collaborating and lesser competitors, especially in liquid bulk ports and corridors.

• Public good digital infrastructure is a strategic asset. Neutral architectures and services like VWTnet/TWIN can underpin clusters and corridors in ways commercial platforms cannot, making them a lever for industrial strategy and resilient decarbonization.

• Early movers can shape the rules. Companies and ports that step into cargo-owner-driven, terminal-centric communities now will help define the standards, governance, and data conventions that others will later follow.

An Invitation to the Chemical Logistics Data-Sharing Community

Chemical logistics faces a huge opportunity. Although the industry is highly optimized for today’s reality, decarbonization, volatility, and tighter links between production and transport are increasing the cost of weak or delayed coordination, especially for liquid bulk flows that will carry future low-carbon fuels and key intermediates. At the same time, the sector already has a firm foundation in discipline and digital maturity. VWT offers a practical path for industry actors to co-create data-sharing infrastructure, starting with terminal and corridor communities that identify where uncertainty propagates, define trust boundaries, agree on a minimal set of intent and progress signals (estimates and actuals), and co-facilitate the necessary adjustments to existing tools like VWTnet, backed by TWIN.

As low-carbon fuels and materials scale, chemical logistics becomes critical infrastructure for the energy transition, and data-sharing for better coordination becomes a strategic and economic requirement and capability. Our invitation is to engage early, pragmatically, and collaboratively in building more reliable, better coordinated end-to-end chains that can support the decarbonization of global transport and logistics, of which liquid bulk is only one part. VWT provides a digital end-to-end infrastructure ready to support the necessary developments, gradually across all supply chains, with chemical logistics certainly a priority.

1 Global Maritime Forum (2025) Assessing the feasibility of the South Africa–Europe iron ore green shipping corridor. Global Maritime Forum, 30 October 2025; North Sea Port (2024) Sweden–Belgium Green Shipping Corridor expands ambition for world’s first green ammonia shipping corridor, 14 June 2024

About the authors

Mikael Lind is the world’s first (adjunct) Professor of Maritime Informatics engaged at Chalmers and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). He is a well-known expert frequently published in international trade press, is co-editor of the first two books on Maritime Informatics and is co-editor of the book Maritime Decarbonization.

Wolfgang Lehmacher is a global supply chain logistics expert. The former director at the World Economic Forum and CEO Emeritus of GeoPost Intercontinental is an advisory board member of The Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society, an ambassador for F&L, and an advisor to GlobalSF and RISE. He contributes to the knowledge base of Maritime Informatics and is co-editor of the book Maritime Decarbonization.

Jeremy Bentham is currently Co-Chair (scenarios) with the World Energy Council, a senior Fellow with Mission Possible Partnership, and a senior advisor to several international organisations including the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. He was formerly the head of scenarios and strategy with international energy major, Shell.

Chye Poh Chua is a VC investor focused on disruptive technologies in maritime commerce and logistics. With four decades of experience across shipping, terminals, and maritime technology, he works at the intersection of commercial reality, governance, and digital infrastructure, with a particular interest in end-to-end coordination in complex, commercially sensitive supply chains.

Philippe Isler has spent more than 25 years designing and implementing solutions to facilitate and optimise international trade. After many years deploying and operating Single Window and traceability systems in developing countries on a commercial basis with SGS, he has, for the past decade, led the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation at the World Economic Forum. In parallel, he has also served on an advisory board at Neste, contributing to efforts to advance the decarbonisation of commercial aviation.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Jens Lund-Nielsen is a pioneer in public–private partnerships for global trade. He co-founded the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation and the Logistics Emergency Teams with the World Food Programme, and has nearly two decades of experience from A.P. Moller – Maersk and PwC. He is co-founder of the TWIN Foundation and trade digitalisation initiatives including ADAPT, TLIP, and 3Sixty, and advises governments, the EU, the UK, and the World Economic Forum.

Per Löfbom is an experienced and certified IT architect with a strong background in IoT, e?navigation, integrations, and platform strategy. He has extensive experiences as an architect, project manager, and IT manager across industry, logistics, maritime and public sector. Additionally skilled in standardization, system design, system development and complex integration environments.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.