Happy Hour at Club-K

(Article originally published in Sept/Oct 2023 edition.)

Housed in a 40-foot shipping container, the Russian-built Club-K missile system shows the extent to which countries like China and Russia are militarizing their commercial fleets.

Operation Serval, 2013: France deploys 5,500 soldiers to Mali to stop Islamist terrorists from declaring an independent state of Azawad in the Sahara Desert. Helping shuttle equipment and supplies to support the operation are the Dixmude, an amphibious assault ship and helicarrier belonging to the French Navy, and two privately owned ro/ro vessels, the Eider and Louise Russ. The mission was a success and, despite logistical challenges, the Malian government asserted itself against the rebels.

It’s the last known major offensive sealift operation by a European armed force.

Fast forward to 2023 and French President Emmanuel Macron has announced the withdrawal of French troops from Niger amidst a general rethinking of its involvement in Africa. A French diplomat, speaking anonymously to Politico, complained that his country had been “… kicked out of Africa” and “We need to depart from other countries before we get told to go.”

The French presence in the African Sahel was regarded as “one of the last symbols of France’s hard power and, in particular, of the country’s self-perception as a great world power,” remarked Djenabou Cisse, who works for the Paris-based Foundation for Strategic Research.

Meanwhile, Europe’s other great world power, the U.K., has four remaining naval auxiliaries remaining under the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), following the release of two of the vessels from their contracts to save money. Originally, six vessels were built, four in Germany by the now-bankrupt Flensburger Schiffsbaugesellschaft (FSG), which we discussed in the previous edition. The U.K.’s Ministry of Defence noted optimistically that, so far, no military equipment had proved too big to be moved by the PFI partnership ships.

The British can also draw on two Albion-class and three Bay-class amphibious landing ships.

“Integrated Military-Civilian Logistics System”

By contrast, China has 474 naval auxiliaries. That’s right – it’s such a big number that it has to be written using Arabic numerals. And the reason is more straightforward and obvious than one might think.

COSCO, now the world’s fourth largest commercial shipping line, is officially part of China’s “integrated military-civilian logistics system,” says Claire Chu, who works for the noted defense sector intelligence firm, Janes. Beijing itself calls this a “military-civil fusion,” and it represents the world’s biggest current peacetime force escalation.

And it’s not new.

In 2019, the Chinese frigate Linyi was resupplied while underway by a COSCO container ship flagged in Hong Kong, the Fuzhou. A statement by China’s Ministry of National Defense in China Military Online praised the “pre-installed” modular replenishment system that loaded cargo onto a wire rope trolley. This “breakthrough,” it was said, “provides a strong logistics support for Chinese navy to go to the high seas.”

It further noted: “Using civilian ships to carry out UNREP for naval ships is a new attempt in the field of naval logistics support. The civilian vessels cover a wide range of routes, thus have large potential for replenishment at sea, which implies remarkable military economic benefits.”

Militarizing the Commercial Fleet

If this information is being disseminated publicly, it stands to reason that China has already developed other capabilities for interplay between military and civilian sectors that are being kept secret. COSCO regularly interacts with high-level military and public officials.

China is far along in militarizing its commercial shipping sector. A 2017 China law requires Chinese transportation companies, and in particular their overseas subsidiaries, to support Chinese military operations when asked.

With that many container ships plying that many routes and with controlling or minority stakes in a variety of ports and terminals around the world (see “When China Shanghais Your Port” in the November/December 2022 edition), COSCO is a major worldwide Chinese sealift asset.

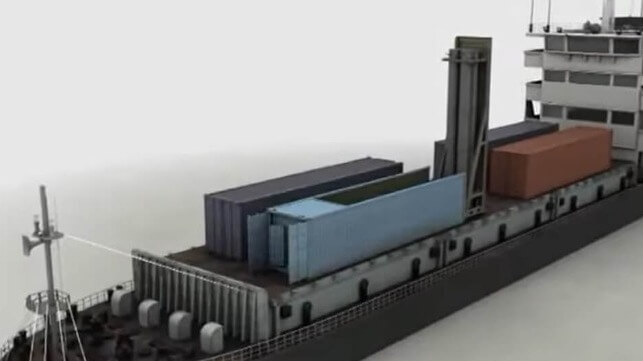

COSCO may also pose a military threat. Russia, with whom China declared a “no limits partnership,” hosts a company called Rosoboronexport, which sells the Club-K missile system. While I would hate to impute ill-will or other less-than-savory motives, it’s notable that the Club-K system is designed to be installed in a double-size, 40-foot equivalent unit (“FEU”) container. It can autonomously fire up to four missiles directly from within the FEU from either land or sea.

Deploying such firepower from inside large numbers of civilian-looking FEU containers would certainly be surprising!

Acknowledging Europe’s Deficits

While these pages have traditionally embraced the free flow of goods, ideas and money, especially when supported by an international, rules-based order, it’s plain that China and Russia are happy to pay lip service to such a system while otherwise working to undermine it. But what can Europe do?

A late 2022 military mobility action plan published by the E.U. at least acknowledges several deficits including differences in Member States’ rail systems and, with respect to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, “the limited capacity of the civilian sector to meet the urgent and possibly large-scale demand of the military in times of crisis.”

While the plan focuses on European deployments, it highlights infrastructural needs that may instigate tension with China. For example, a Chinese-owned terminal could be one of the mentioned “transport nodes and logistical centres that provide the required host- and transit nation support and sustainment to facilitate the deployment of troops and materiel.” China holds an interest in dozens of the European ports identified as “core” in an included map.

If past decades have shown anything, though, it’s that Europeans have an incredibly tough time choosing guns over butter. It’s much easier to write an action plan than to actually take action. Saying “no” to Chinese port investments, building out strategic sealift capacity or even supporting domestic shipbuilding have been elusive.

The U.S. as Counterweight

That leaves the U.S. as the only counterweight to Chinese ambition in Europe. The U.S. has a long-standing agreement to access U.S.-flagged, U.S.-built commercial ships, generally sailing under the protection of the Jones Act, for strategic sealift. It also has access to the Military Sealift Command with its 125 civilian-crewed, typically foreign-built (and thus cheaper) vessels.

This provides a baseline, but as the Jones Act fleet shrinks over time, meaning also that fewer American sailors are available, defense officials have asked for a reassessment of current policy. And in contrast to COSCO, the Jones Act fleet is only available for strategic sealift. It is not a generalized military auxiliary.

One change could be requiring ships that sail for the Military Sealift Command to also be built in the U.S. With the typical age of one of these ships at 44 years, it’s time for a major rejuvenation of the force. Further, the Maritime Administrator has previously complained that there are insufficient large drydocks to adequately service the sealift fleet, which hurts readiness.

Domestically commissioning several newbuilds could address these problems by supporting U.S. shipbuilding, but that costs money. And the military’s preference for versatility is at odds with the needs of commercial shipping: Big, more cost-efficient ships can’t enter every port because they frequently require a deeper draft. They may also lack cranes, preferring to rent specialized port-side equipment on an ad hoc basis.

Indeed, as much as money appears to be the biggest problem for the U.S. and Europe, it’s of no concern to China. From 2010 to 2018, China spent over $132 billion on state support for its shipping sector. More recent numbers are hard to find, but it’s likely that such spending has grown further.

Meeting the Challenge

Meeting the challenge posed by China and, to a lesser extent, Russia, is going to be hard. European leaders have generally been less willing to bear the strain than their American counterparts. But even in the U.S., many voices advocate the easy path.

The Cato Institute, for example, laments that the Jones Act is a “burden America can no longer bear,” arguing that it causes “higher prices” and “inefficiencies.” It dwells on the problems that the Jones Act has not been able to fix, e.g., the declining number of American shipyards, as also mentioned previously by the Maritime Administrator, while praising Europe for finding “competitive niches” like building cruise ships and megayachts, two sectors that have fallen embarrassingly on their faces since Cato published its article in 2018.

A free-market solution would be difficult enough to find even without the seemingly boundless subsidies China is willing to provide to its state-affiliated actors. But with shipyards, shipping companies and even banks that finance ships enjoying the benefits of an open spigot of Chinese government funds, maintaining military readiness, sustaining a functioning commercial maritime sector and retaining enough skilled sailors will require an array of smart public policies.

The Jones Act is the foundation of such a system, but a foundation is only the beginning of a house. It will take more.

For Europe, the road is steeper. Just having America’s problems would represent a huge step forward. In strategic terms, Europe isn’t even a player right now – it’s the playground.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Europe’s core ports have been deeply infiltrated, and Europe’s establishment is often ideologically sympathetic toward China and Russia, seeing in them a commercial opportunity they would hate to miss, no matter the collateral damage to others in human terms. Finding European sailors, or European-flagged ships or ships built in Europe is becoming a tougher ask with each passing day.

Who knows – maybe a European version of the Jones Act would be a place to start. If you’re going to build a house, even if it takes a while, you’re going to need a solid foundation.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.