Why are Bills of Lading Issued in Sets of Three?

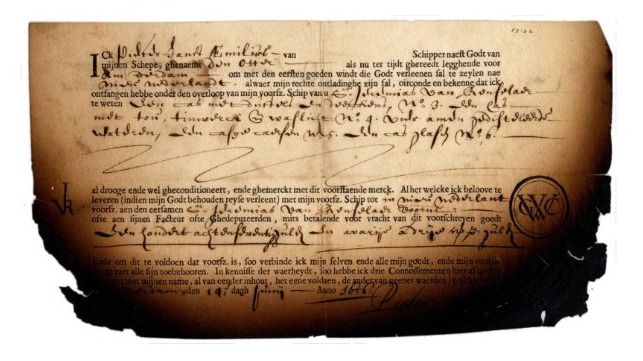

Original bills of lading are normally issued in identical sets of three. The master can act by delivering against the first original presented for delivery of the cargo. The practice is described in the phrase "the one of which being accomplished the others to stand void.”

The issue of a set of three original bills provides or implies, by itself, that delivery will only be made against presentation. The practice dates back to the sixteenth century and is designed to allow the shipper to retain one original, provide the second to the carrier and send the third to the consignee by different methods.

Willies J held in the English case of Glyn Mills Currie & Co v East & West India Dock Co:

I think the bill of lading remains in force at least so long as complete delivery of possession of the goods has not been made to some person having a right to claim under it.

This is explained in the judgement:

The nature and extent of the obligation, undertaken by the shipowner, to deliver the goods at the end of the voyage, must depend upon the terms of the bills of lading, which contain his contract with the shipper: and every assignee of a bill of lading has notice of, and must be bound by, those stipulations, which have been introduced into the contract, for his own protection, by the shipowner. In the present case the master, for the convenience of the shipper, subscribed to three bills of lading of the same tenor and date, by which he undertook to deliver the goods, at the port of London, to Cottam & Co. or their assigns; and each bill of lading bore the usual affirmation by the master that he had signed three in all, "the one of which bills being accomplished, the others to stand void."

That is a stipulation between the shipper and the shipowner, and it is plainly intended to give some measure of protection to the latter, after he has delivered the goods upon one of the bills of lading, against subsequent demands for delivery from holders of the other bills of the set.

It is (in my opinion) inconsistent with any reasonable construction of the stipulation that the shipowner should be held liable in all cases to deliver to the true owner of the goods, because this interpretation would give him no protection. The stipulation can have no intelligible meaning or effect if it does not, under some circumstances, enable the shipowner to resist a claim for second delivery by the holder of a bill of lading.

On the other hand, it is obvious that the stipulation is meant exclusively for the protection of the shipowner, and is not intended to confer upon him the right to select the person to whom he shall deliver or to affect the rights inter se of the holders of the bills of lading. That being so, I think that the natural and reasonable construction of the language of the contract is that the shipowner is to be exonerated by delivery upon one of the bills of lading, although it does not represent the property in the goods - with the qualification that, bona fides being an implied term in every mercantile contract, the delivery must be made in good faith and without knowledge or notice of any right or claim preferable to that of the person to whom he so delivers.

Subsequently at a later part of the judgement:

Before the close of the argument, the noble and learned Earl (Earl Cairns) suggested, for your Lordships' consideration, that the practice of having so many parts of the bill of lading all in the nature of originals was introduced for some purpose of convenience to the consignor or consignee, and that the concluding passage, "the one of which being accomplished the others to stand void," was probably intended for the protection of the shipowner. He further suggested that, in carrying into effect that object, the true interpretation should be that if the master, acting in entire good faith, delivered the cargo on one part of the bill of lading either to the consignee named in it as such, or to an indorsee of one part, he would have "accomplished" the bill of lading so far as it is a contract for carriage and delivery, and be protected even though another part of the bill of lading should prove to be outstanding in the hands of a prior indorsee for value, but of which the master had no notice.

If the original bills of lading are issued in sets of identical originals, the question that arises is whether buyers can demand the entire set, all three copies. The English Court of Appeal in the case of Sanders Bros v Maclean & Co. answered that they could not.

Bowen LJ explained:

It is plain that the purpose and idea of drawing bills of lading in sets – whatever the present advantage or disadvantage of the plan – is that the whole set should not remain always in the same hands.

The shipper may prefer to retain one of the originals for protection against loss of the document or transfer it to their agents.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Philip Teoh has been in legal practice in Singapore and Malaysia for the past 31 years handling both contentious and non-contentious areas. He is the partner heading the Shipping, International Trade, Insurance Practice at Azmi & Associates Malaysia. He is an SCMA arbitrator and works with the key International arbitration centers of LMAA, EMAC, ICC, LCIA, AIAC, KCAB and others.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.