Restriction of Paris MoU Data Poses Serious Threat

I like to party on New Year’s Eve. This year, though, my celebrations will be somewhat muted. That’s because when midnight strikes on December 31, it won’t just usher in 2019; it’ll also mean the end of open access to port state control data collected by the Paris MoU. The decision to do this poses a serious threat to maritime safety and security.

It’s nothing to cheer, because I know how important this data is for maritime safety and security. Port state control is designed to ensure that only seaworthy ships that comply with international law are able to sail and visit ports. Vessels are inspected in port, creating a safety record for each one. The results are made publicly available by regional bodies - such as the Paris MoU (for Europe) - to further promote maritime safety and security.

The changes may seem trivial. Port state control data will still be gathered when a European port inspects a vessel. It’ll still be collected by the Paris MoU, and it’ll still be accessible. What companies, governments and insurers will no longer be able to do is download the data en masse into their risk models, undermining their accuracy (your marine insurance actuary is unlikely to manually check the data for 30,000 individual vessels to help price their policies).

This matters because port state control data is dynamic and constantly updated; it’s an important predictor of risk. For the past 20 years, organizations have built models using Paris MoU data. It’s enabled them improve maritime safety and security. Specifically, it’s helped catch smugglers, detain unseaworthy ships and predict which vessels are likely to have accidents.

The Paris MoU itself uses its own data to rank vessel flags according to safety risk. Ships flying blacklisted flags - including Congo, the Comoros and Cook Islands - are more likely to be inspected, detained and even banned (two of the five foreign-flagged vessels detained by the U.K. in October flew the Cook Islands flag).

From the perspective of border protection, Paris MoU data is equally important: a Windward study showed that ships flying blacklisted flags represent fewer than two percent of all merchant fleet vessels. Yet they account for more than one-fifth of all smuggling events since 2015.

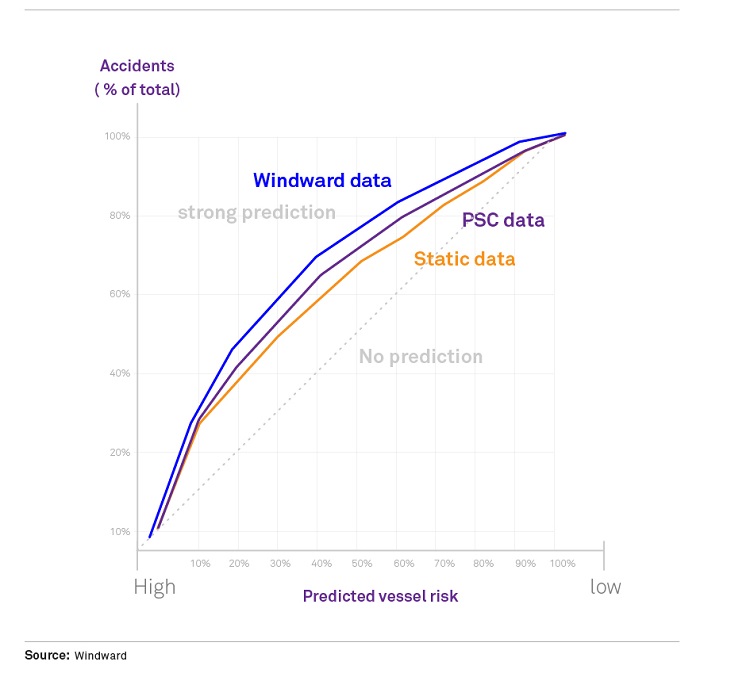

The data backs this up. The chart (below) shows how models using Port State Control Data (purple line) are better predictors of accidents than those which don’t (orange line).

Even before the Paris MoU decided to restrict access to its data - a move which reportedly arose from a spat between the Netherlands and a ship vetting company called Rightship - the high seas were a dangerous place to work. As Grahaeme Henderson, Shell Vice-President for Shipping noted: “Our shipping industry has a fatal accident rate 20 times that of the average British worker and five times that of construction. Simply put, that is unacceptable. And it needs action.”

The Paris MoU has been taking action, almost doubling its membership and leading the charge to help eliminate substandard shipping. So you’d think it would want to make every effort to help external organizations support - and even enhance - its achievements by using its data. That it’s now about to do the opposite makes its decision even stranger.

As a former naval officer who carried out ship inspections, I know that small details can indicate big problems. Take the passenger ferry, Excellent. It was inspected twice in 2018. One deficiency was found. On October 31, it crashed into a crane in the port of Barcelona, setting off a fire. The accident wasn’t preordained. But analyzing Paris MoU data shows us that vessels that have even one deficiency - no matter how minor - are almost four times more likely to have an accident in future.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Accidents like these will happen. Paris MoU data doesn’t turn models into a crystal ball, but for many organizations, it’s the closest thing they’ve got, and plays a crucial role in day-to-day decision-making and risk evaluation. Restricting access to it is, in the words of Rightship founder, Warwick Norman, a “regressive” step; it puts partisan interests above those of maritime safety and security. The decision to do so should be reversed - before it’s too late.

Ami Daniel is Co-Founder and CEO of maritime risk analytics company Windward (www.wnwd.com).

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.