New Deal to Decarbonize Shipping Isn’t Enough

Here’s How Global Trade Can Reach Net-Zero

[By: Wim Naudé]

Much of the world has been left disappointed by the Glasgow Climate Pact, the outcome of the COP26 climate conference. Scientists say it will not lead to the decarbonization required to limit global warming to less than 2°C in the coming years.

Yet there were steps forward, including the Clydebank Declaration for Green Shipping Corridors. This has seen 22 countries, including the US, UK, Japan and Germany, committing to establishing routes in which shipping is to be free of carbon emissions. There are to be six by the middle of the decade, and more by 2030.

This is good news, given that international freight transport contributes about 7% of total global carbon emissions, and maritime shipping alone around 2.5%. But there are limits to what this agreement can achieve, and numerous other important issues around shipping and global trade were overlooked by the conference. So what else should have been done?

What COP26 ignored

The problem with the agreement on green shipping corridors is that only about 200 out of over 50,000 ships globally active in trade will be green by 2030. This reflects the costs and complexity of decarbonizing shipping. Maersk, which owns the world’s largest shipping fleet, will apparently only have eight ships ready to run on methanol by 2025.

The International Maritime Organization does have a target for cutting carbon intensity from ships by 40% by 2030, but COP26 was a missed opportunity to push the industry for more rigorous commitments, which were not included in the Paris agreement in the first place.

One other glaring omission from the conference was any legally binding obligations for countries to include explicit targets for the decarbonization of shipping (or air freight) in their nationally determined contributions, which are individual national commitments for reducing emissions.

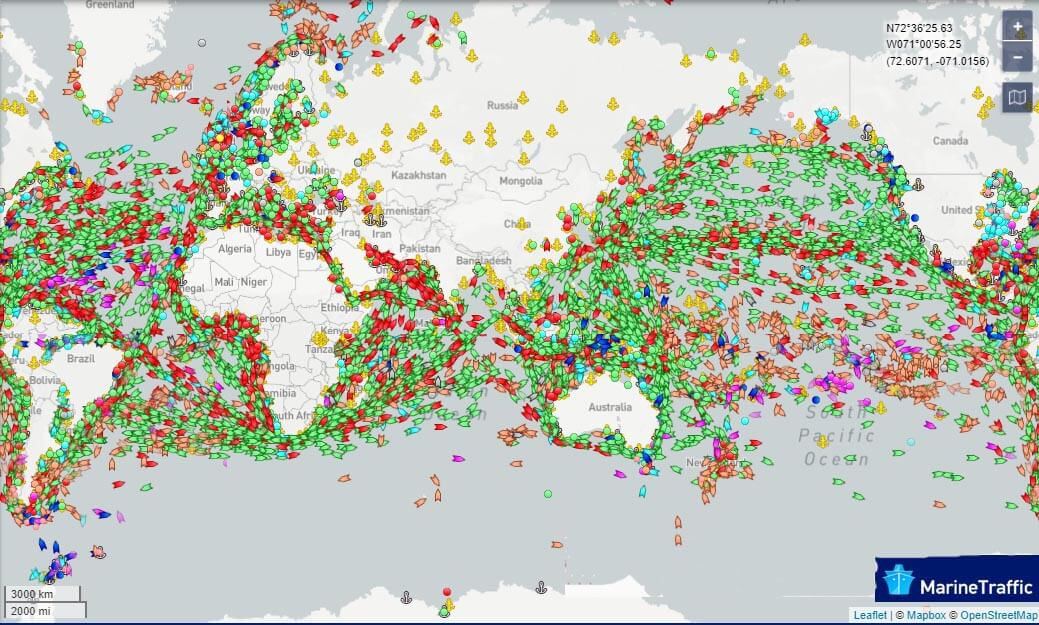

50,000 ships in motion

Representation of all the ships at sea on November 26, 2021 -- image courtesy of Marine Traffic

Two other very specific and related problems have also been neglected in relation to shipping and trade. The first is the so-called “Jevons paradox”, and the second is the EU’s proposed carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

The Jevons paradox in this context relates to the possibility that decarbonizing the sector could lead to more innovations that drive down shipping costs. This could boost consumer demand for international goods, which would mean increased carbon emissions because of more manufacturing of goods. So, decarbonizing shipping isn’t enough. We need to rethink what and how much we trade as well, and this was not on the agenda at the conference.

Of course, international trade is not all bad for carbon emissions. It can be a way to spread environmentally friendly goods and technologies throughout the world. Indeed, the growth of the global trade in what the OECD defines as “environmental goods” is now outpacing trade in goods overall, driven by solar panels and other renewable-energy products.

Yet countries could do more to encourage the trade in environmental goods to unlock the economies of scale required to make more products cheap enough for mass market. Too many countries levy import tariffs on them, so an obvious step would have been to agree tariff reductions.

It would also have been useful to carefully extend the list of environmental goods. For example, should aluminum, used in solar panels, be defined as an environmental good?

Countries could do more to help local providers to find export markets. As I have explained elsewhere, there are some good ways of developing algorithms to take advantage of big data to help identify such opportunities.

Many countries’ approaches to exports can also be traced back to hub-spoke relationships established during the colonial period, and in more recent times the emergence of China as an African trade partner. Most African nations, for example, have almost exclusively focused on mass production for faraway international markets rather than developing their domestic markets. The world needs to take steps to change this system, so that both environmental and non-environmental goods are more commonly produced closer to their consumers.

Carbon import taxes

Since July, the EU has been proposing a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” (CBAM) to essentially tax imports from non-EU countries with embedded carbon emissions (meaning all emissions generated in manufacturing the goods and the materials they’re made with). The US is also considering such an initiative.

While these are well-meant initiatives aimed at penalizing firms who move production of carbon-emitting goods to countries with looser environmental regulations, they may have the unintended effect of reducing the trade in environmental goods. Again, there was no discussion of this in Glasgow.

Admittedly these effects will be limited to the goods covered under the mechanisms. For example, the proposed CBAM would only cover – initially – 3.2% of goods imported into the EU.

But the definitions that determine which goods are included could be expanded in future, posing more of a threat. For example, were aluminum products to be included, it could hit solar panels hard.

On top of this, there is the unintended consequence of punishing producers in developing countries for not meeting EU emissions standards. This is particularly unfortunate considering that rich countries have failed to meet their climate-finance commitments made in 2015 at COP21 in Paris.

As Frans Timmermans, the executive vice president of the European Commission, suggested at COP26, if other countries take adequate measures to decarbonize it would “make the introduction of CBAM not necessary”. This mechanism needs to happen alongside the EU fulfilling its commitments towards climate finance to developing countries, particularly supporting green industrial policies, if Brussels is to avoid further accusations of “climate colonialism” in future.

About the author: Wim Naudé is Professor Economics, Cork University Business School, University College Cork, Ireland; Affiliated Researcher, Environmental Research Institute, Cork; Visiting Professor, RWTH Aachen University School of Business and Economics, Germany. Fellow, African Studies Centre, Leiden University, the Netherlands; Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. His scholarly work is concerned with the relationship between entrepreneurship, technological innovation, trade and sustainable economic development.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage of COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world. The story may be found in its original form here.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.