Avoiding Non-Compliance in Ship Generated Food Wastes

Seeing custom officers stopping certain food products (among other things) at the airport, one might find it hard to contemplate the possibility of the same stuff being pumped into city's sewer from the international ships - by design. The joint paper below explains why some system designs may have more than IMO instruments to answer to.

Food Waste Disposers and Their Compliant Applications Onboard Ships

Co-authored by

Dr. Wei Chen, Future Program Development Manager, Wartsila UK Ltd, UK

Niclas Karlsson, Managing Director, Clean Ship Scandinavia AB, Sweden

Endorsed by

Antony Chan, Engineering Manager, Victor Marine Ltd., UK

Benny Carlson, Chairman and owner, Marinfloc, Sweden

Dr. Daniel Todt, Project Manager R&D, Ecomotive AS, Norway

Helge Østby, Senior Technical Advisor, Jets Vacuum AS, Norway

Tjitse Lupgens, Advisor Environmental, Boskalis, Netherlands

Dr. Gerhard Schories, Head of Institute, ttz Bremerhaven, Germany

Karolina Apland, MEnv, Environmental Assessment and Permitting Manager, Terragon Environmental Technologies, Canada

Ronni Palmqvist, Director and Owner, Dancompliance ApS, Denmark

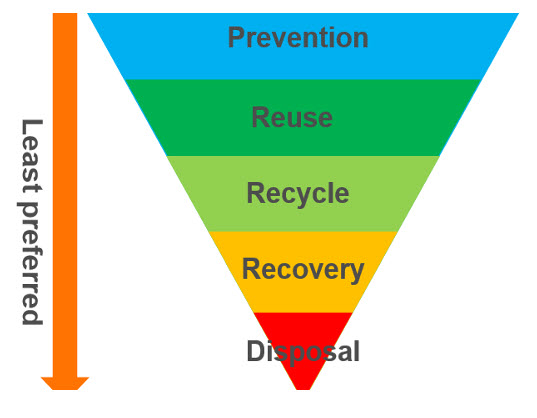

Waste management hierarchy

Modern society’s waste management hierarchy (Figure 1) continues to shift organic wastes towards reuse and recycling, and away from landfills [1]. When it comes to food waste, some countries and regions promote its segregation from other municipal solids wastes. Segregated food waste can be anaerobically digested. In addition to biogas production, the digested biosolids can be used for agriculture and soil conditioning. However, food waste segregation can emit odor, require transportation and entail collection fees. Therefore, alternative solutions, such as a food waste disposer (Figure 2), are available.

Figure 1. Waste management hierarchy

Figure 2. Food waste disposer [2]

The food waste disposer grinds food waste into small pieces which are washed down the drain. A food waste disposer contributes 20 grams/person/day of solids and four to eight liters/unit/day of water [3,4,5], thereby increasing the risks of blockages and corrosions in the sewer, and creating the potential need for additional investments at the receiving municipal wastewater treatment plant, while increasing its energy consumption and sludge production [2,6].

Food waste disposers are encouraged in some countries [7, 8], restricted in others [2, 9, 10]. However, the waste management hierarchy remains the common objective even at regional and local levels: the worst disposal route for food waste is to landfill it, or to burn it without energy recovery.

The marine industry should be no different.

Ship generated food waste and biosecurity risks

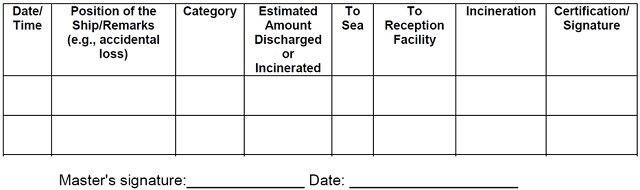

Ship generated food waste is regulated by the IMO’s MARPOL Annex V Convention. It has three permissible disposal routes which must be recorded and signed by the ship’s master (Table 1): to sea, to reception facility and to incineration.

Table 1. Garbage Record Book for food wastes, MEPC. 201(62).

The aim of onboard incinerators is to reduce the storage of garbage. They are increasingly restricted in coastal waters due to their emissions. Their batch operations do not facilitate energy recovery in tight spaces. Consequently, the incineration of food waste onboard may be the least green option under the waste hierarchy. Alternative thermal waste technologies are being developed.

Offloading food waste in ports can be tricky, not least because of a general lack of port reception facilities. It can carry biosecurity risks. Some countries with economically important agriculture sectors such as European Union member states, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the U.S. have imposed strict controls on food waste from international origins due to its biosecurity risks.

In these countries, food waste and food contaminated garbage are subject to strict quarantine requirements. Under European regulation EC 1069/2009, such food waste is “international catering waste” or Category 1 Material. It must be transported in sealed containers to licensed incineration facilities or to landfill sites for deep burial. Biosecurity takes priority.

The biosecurity concern associated with food waste is unique to the international marine and aviation industries. Practices and solutions that are perfectly viable ashore may not be so for ships.

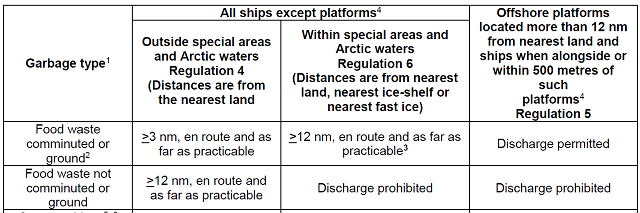

Luckily, the marine industry has a compliant option which does not involve landfill or incineration: food waste can be discharged into the sea. It readily closes the cycle of this organic material by following some simple steps under the existing rules (Table 2).

Table 2: Discharging of food waste into the sea (refer to MARPOL Annex V for footnotes)

This could be the end of the story, …but no.

Making food waste “disappear”

Some ships are designed in such a way that the food waste “disappears.”

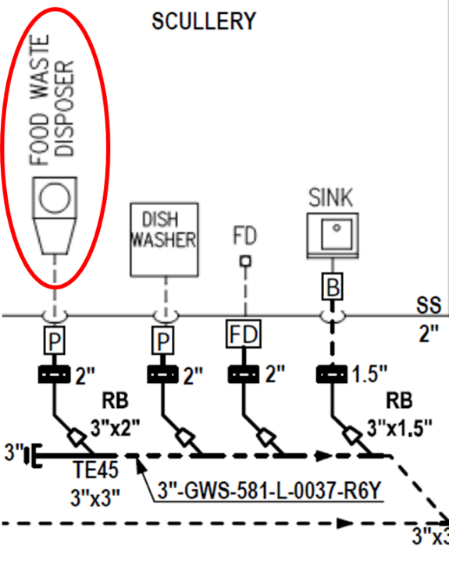

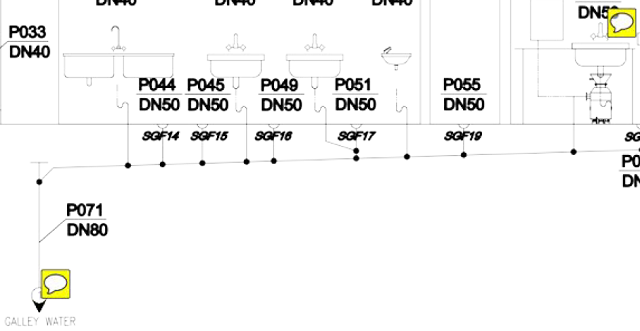

When food waste disposers are used on ships, they are sometimes connected to the gray water systems (Figure 3) and at times to the sewage treatment plants. Critically, from the point where the food waste goes into these systems, it disappears from the ship’s piping diagrams and is never to be seen again.

Such designs have been approved, and the situation is known to the authorities for years [11].

Figure 3. Two examples of food waste being connected to gray water systems

Compliance?

MEPC.295(71), the 2017 Guidelines for the implementation of MARPOL Annex V, state that food waste “should be directed into an appropriately constructed holding tank when the ship is operating within an area where discharge is prohibited.” Failing to provide such a designated food waste holding tank has consequences. Food waste is then sent into ship’s sewage and gray water systems and disguised as sewage, sewage sludge or gray water. This represents a failure to comply with the IMO’s MARPOL Annex IV and Annex V.

Just imagine how a Garbage Record Book can be truthfully completed to reflect such a “disappearance” of food waste.

For those who intend to mix food waste with other wastes, the existing rules are clear:

Regulation 4.3 of MARPOL Annex V states, when garbage is mixed with or contaminated by other substances prohibited from discharge or having different discharge requirements, the more stringent requirements shall apply. Thus, because gray water is not regulated, food waste rules shall apply to the mixture of gray water and food waste.

Regulation 11.4 of MARPOL Annex IV states, when the sewage is mixed with wastes or waste water covered by other Annexes of the present Convention, the requirements of those Annexes shall be complied with in addition to the requirements of this Annex. Because sewage and food waste rules can each be more stringent, both rules shall apply to the mixture of sewage and food waste.

Crucially, the rules ashore designed to protect local communities from biosecurity risks have been circumvented, by design.

The food waste disposer is not at fault. The solution is simple, namely to keep discharges from food waste disposers separate from the other wastes, and to stick to the rules. Alternatively, should the mixing of food waste and other waste be inevitable, the mixture should at least be labelled as food waste. As such, the mixture can be suitably managed, recorded and declared in compliance with the rules at sea and ashore.

When such simple, clear and important environmental rules are being circumvented by such non-compliant practices created by design, one can only ponder, why?

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

References

[1] Directive 1999/31/EC on the landfill of waste (1999)

[2] Examining the Use of Food Waste Disposers, EPA Strive Report Series No. 11, Carey. C., Phelan, W., Boland, C., EPA, Ireland (2008) https://docplayer.net/storage/41/22638183/1547124645/HN0yuANdslv1duYXuAQnSQ/22638183.pdf

[3] Wastewater Engineering, Treatment and Reuse, 4th ed, Metcalf & Eddy (2004)

[4] Small and Decentralized Wastewater Management Systems. Crites, R. and Tchobanoglous, G., McGraw-Hill (1998)

[5] Tank-connected food waste disposer systems – Current status and potential improvements, by A. Bernstad, et. al., Water and Environmental Engineering, Department of Chemical Engineering, Lund University, Sweden, Waste Management 33 (2013) 193–203

[6] The effects of food waste disposers on the wastewater system: a practical study, Thomas, P., Water & Env. J. 25: 250-256 (2011)

[7] The potential of food waste disposal units to reduce costs – a literature review, Local Government Association, London (2012)

[8] Surahammar – a case study of the impacts of installing food waste disposers in fifty percent of households. Evans, T.D., Andersson, P., Wievegg, A., Carlsson, I. Water Environ. J. 24:309-319 (2010)

[9] The Impact of Food Waste Disposers in Combined Sewer Areas of New York City, New York City Department of Environmental Protection (1997)

[10] Commercial food waste disposal study, Lawitts, S. W., New York City Department of Environmental Protection (2008)

[11] The Management of Ship-Generated Waste On-board Ships, EMSA/OP/02/2016, by Delft, CE Delft, Jan. 2017.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.