A Fighting Merchant Ship for the 21st Century

[By Steve Wills]

The East Indiaman was an iconic vessel from the age of “fighting sail” that combined the features of a robust, long-range cargo ship with the weapons of a frigate-sized combatant. One source defines these vessels as, “large, strongly built vessels specifically designed by the great trading companies of England, France and Spain for the long and dangerous passage to the Far East. They were, as a type, powerfully-armed and carried large and well-disciplined crews.” John Paul Jones’ famous flagship USS Bonhomme Richard was such a vessel, formerly of the French East Indies Company.

The great mercantilist trading companies of the age of sail are long gone, but the idea that a heavily armed merchant ship might again more fully participate in naval warfare has new credence. The advent of the large, survivable container ship, with the potential for containerized weapon systems changes the calculus of the last century where merchant ships were soft targets requiring significant protection. If properly armed and crewed, U.S. owned and U.S. government chartered container ships have the potential to become powerful naval auxiliaries capable of defending themselves and presenting a significant risk to those that might attack them. Such ships could free naval escorts for other combat duties and contribute toward short term sea control while otherwise engaged in logistics operations.

The Historical East Indiaman

The East Indiaman was a significant vessel type throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. While designed to carry high value cargo through dangerous waters, they were capable of being quickly up-armed to the point where some could mount as many guns as a major warship. For example, the British Royal Navy (RN) purchased the British East India Company (EIC) vessel Glatton in 1795 for warship conversion. Originally armed with 26, short-range, but powerful carronade weapons, she was up-gunned by the RN to a total of 56 guns and served in several engagements with French, Dutch, and Danish forces, notably the 1802 Battle of Copenhagen when she was commanded by William Bligh; formerly the master of the mutinous Bounty.

Their large size caused pirates and French naval vessels to often mistake them for more heavily armed ships of the line. When actually engaged in battle, the East Indiaman usually performed well if not excessively overmatched. The East Indiaman General Goddard operating with one RN ship of the line and several other company ships captured eight of her Dutch East Indiaman counterparts off Saint Helena in 1795.

They were however vulnerable if overmatched. In July 1810, two company ships; the Ceylon and the Windham, both with respectable frigate armament of near 30 guns each, were captured by a strong French frigate squadron. The East Indiamen still put up significant resistance to the French attack, allowing a third ship of their convoy to escape.

20th Century Armed Merchantmen

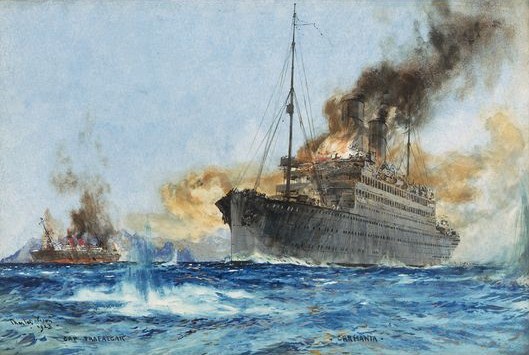

The end of the British East India Company after the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the advance of modern technology, and the 1856 Declaration of Paris where Europeans powers took a firm stand against privately owned warships helped eliminate the concept of a heavily armed cargo ship. Armed merchantmen returned however in both World Wars as nations sought to protect their trans-oceanic convoys from German U-boats and surface raiders. In the First World War, nations armed merchants with old naval weapons as a defense against both surface warships and surfaced submarines. These ships generally gave good accounts in battle - sometimes against similar craft, as when the British armed passenger ship RMS Carmania sank the German armed liner SMS Cape Trafalgar in a rather bloody battle at close range in 1914. Also active were disguised raiders for surface action and Q-ships to lure submarines to destruction.

Carmania sinking Cap Trafalgar off Trinidad, September 14, 1914 (Charles Dixon / Wikimedia)

World War II again saw all of these auxiliary naval units in action. In the first six months of the war the U.S. lost 350 merchant ships and 3000 merchant seaman. Raiders could sometimes defeat purpose-built warships if they retained the element of surprise and/or disguised themselves as peaceful vessels. The German raider Kormoron was able to fatally wound the light cruiser HMAS Sydney under these conditions but was lost herself due to return fire from Sydney. The U.S. again assigned naval personnel as weapons crews on U.S. merchants, primarily against air and surface attack. The U.S. Merchant Marine Armed Guard was assigned to this mission during the Second World War and suffered over 1800 dead in the course of its operations.

The practice of arming merchantmen again fell into decline after the Second World War, although naval auxiliaries continued to be armed with defensive weapons through the end of the Cold War. After the fall of the Soviet Union and in the downsizing of the U.S. Navy that followed, nearly all commissioned supply and auxiliary ships were shifted over to the authority of the Military Sealift Command (MSC) in an attempt to save money through re-crewing with a smaller number of civil service MSC mariners rather than with Navy sailors. A 1990 Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) report suggested, “The Navy would save $265 million annually if the service turned over 42 support ships and tenders to MSC.” The study attributed the annual savings to much smaller crew sizes on MSC ships. It reported, for example, that civil service crews on a Navy oiler would be half the crew size the Navy used on those ships.

The auxiliaries assigned to MSC were disarmed of weapons upon transfer from the Navy, and those built or added since have not been equipped with them. However, some classes such as the Lewis and Clark T-AKE class are “designed with appropriate space and weight reservations “to allow future installations of self-defense systems as required.”

A New Breed of Cargo Carrier

Maritime technology has in effect come full circle with the advent of extremely large container ships that effectively carry half the cargo weight of an entire World War II convoy with a single hull and larger than all of the world’s combatant warships, some even larger than U.S. nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. Pioneered by the American President’s Line under the leadership of Ralph Davies in the late 1950s and early 1960s, container ship growth in size and numbers has been astronomical with nearly 90 percent of all world commerce moved by these ships and their “twenty/forty foot equivalent length TEU” containers now commonplace throughout the globe. So-called “Panamax” container ships stows 5,000 TEUs and the “Super-Panamax” size supports 13,000 TEUs. The very largest of these vessels support over 20,000 such containers.

Maersk Line operates better than 600 large container ships (about 15 percent of the global fleet). 86 ships are ultra-large, Super-Panamax vessels, and Maersk builds about 20 ships per year. This creates the opportunity to incorporate underwater signature control and survivability measures including foundations for modular combat systems in huge mass production hulls for MSC habitually chartered ships. The hull speed ratio (~0.6), the ship fineness ratio, and the huge slow speed props gives a sustained sea speed of 24 knots and an acoustically silent speed that with non-cavitating props that may well exceed 24 knots.

21st Century East Indiaman

TEU containers can support more than just cargo. In recent years some nations have developed a variety of “containerized” weapon systems to include guns, mortars, small missiles and even larger cruise missiles. The combination of the very large container ship, vast numbers of containers per ship, and containerized warfighting tools offers the possibility of a 21st century East Indiaman. Such a ship might field several dozen “militarized” containers with offensive and defensive weapons, sensors, and the communications equipment needed to link the ship to larger, regional battle networks. If not already possessed of helicopter facilities, additional containers could support rotary wing aviation. The vessel might carry large numbers of unmanned air vehicles for both offensive and defensive missions. They won’t have large crews for damage control and their container-based combat systems may likely be fragile and not capable of sustained combat as a warship could.

A 7,000-ton frigate’s combat systems could weigh about 1050 tons, about the equivalent of 35 TEU loads and might occupy 70 TEUs of space. If a container load for the modular combat system must supply power as well – figure 100 TEUs – a small fraction on a 5000 TEU PANAMAX ship’s cargo space. Erecting the modular combat system at sea might constitute a larger challenge unless the ship was designed for the purpose and had self-enablement cranes. That said, such capabilities might be enough to repel an attack on a convoy by light or medium enemy forces. Like their 18th century forebears, 21st century armed cargo ships could in effect escort themselves with significant self-defense capabilities and magazine spaces equivalent to those of medium-sized warships. The Israelis and the Russians are already experimenting with these concepts.

Israeli LORA launch test

Russian containerized Club-K missile launcher

While not built to warship survivability standards, the sheer size of modern container ships contributes to their survivability rating. Large merchant ships that have been the victims of attack since the 1980s have shown remarkable resiliency in resisting damage. In 1987 the large oil tanker Bridgeton, a reflagged Kuwaiti vessel being escorted by U.S. Navy ships as part of Operation Earnest Will mounted in response to the 1980s “tanker war,” shrugged off a mine hit and continued operations. A similar weapon disabled the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts, a purpose-built convoy escort ship. The 21st Century East Indiaman could free up escorting warships for more offensive actions. The price tag for such a vessel might be relatively low, with most costs being associated with the additional containerized weapons and sensors, as well as the small Navy crew needed to operate the vessel.

The U.S. Military Sealift Command (MSC) as a Source

While the current MSC fleet has few container ships ready for armament, the Civil Mariners are thinking again about how to operate in a more contested environment than that of the last 30 years. Of the combat logistics force, the T-AO-205 and T-AKE-1 classes already have excellent signature control. They can be given a guided missile frigate (FFG) equivalent combat system as part of their new construction design or for T-AKE at mid-life overhaul. There has also been informed discussion on the legal implications of arming civilian vessels. An armed MSC ship acting as a combatant risks blurring the legal lines between military and civilian personnel. Civil Service Mariners may need to be designated as U.S. Navy reservists under special cases such as active wartime operations in order to avoid having civilians operating weapon systems. Such discussions would likely become academic at best in the midst of a high end war where logistics ships would be a prime target.s

MSC usually charters container ships and tankers from large operators such as Maersk. These operators are continuously building ships in production numbers. Container ships and tankers are much larger than combat logistics ships. The operators can design features into the ships MSC habitually charters such as underwater signature control, side protection systems, and AI controlled robotic damage control and appropriate adaption for modular combat system installations at little additional cost. Many of the features may be suitable for general commercial use in that the ships can approach conflict areas more closely and may enjoy lower insurance rates.

Moving Ahead with Armed Merchantmen

While there remain considerable legal and policy issues regarding the concept of merchant ships armed with shipping container-based weapons, the technology appears ready for use. Such vessels could add to fleet size and free destroyers and littoral combatant ships for other missions other than convoy escort. The question is whether or not the U.S. Navy would embrace the idea of an armed container ship as a combat unit in its own right. Given the current size of the fleet and the potential need for high endurance escorts for the Navy’s replenishment force, a force of 21st cargo ships outfitted with frigate-level armament to escort themselves makes good financial and operational sense.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Steven Wills is a Research Analyst at CNA, a research organization in Arlington, VA, and an expert in U.S. Navy strategy and policy. He is a Ph.D. military historian from Ohio University and a retired surface warfare officer. These views are his own and are presented in a personal capacity.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.