U.S. Navy Agrees to Limit Sonar Activities

A federal court in Honolulu entered an order settling two cases challenging the U.S. Navy’s training and testing activities off the coasts of Southern California and Hawaii on Monday.

The order secures long-sought protections for whales, dolphins and other marine mammals by limiting Navy activities in vital habitat. The settlement stems from the court’s earlier finding that the Navy’s activities illegally harm more than 60 separate populations of whales, dolphins, seals and sea lions.

The order secures long-sought protections for whales, dolphins and other marine mammals by limiting Navy activities in vital habitat. The settlement stems from the court’s earlier finding that the Navy’s activities illegally harm more than 60 separate populations of whales, dolphins, seals and sea lions.

For the first time, the Navy has agreed to put important habitat for numerous populations off-limits to dangerous mid-frequency sonar training and testing and the use of powerful explosives. The settlement aims to manage the siting and timing of Navy activities, taking into account areas of vital importance to marine mammals, such as reproductive areas, feeding areas, migratory corridors and areas in which small, resident populations are concentrated.

Many of the conservation organizations who brought the lawsuits have been sparring legally with the Navy and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the agency charged with protecting marine mammals, for more than a decade, demanding that the Navy and Fisheries Service comply with key environmental laws by acknowledging that the Navy’s activities seriously harm marine mammals and taking affirmative steps to lessen that harm.

“We can protect our fleet and safeguard our whales,” said Rhea Suh, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council, whose lawyers challenged the Navy’s activities in Southern California and Hawaii on behalf of NRDC, Cetacean Society International, Animal Legal Defense Fund, Pacific Environment and Resources Center, and Michael Stocker. “This settlement shows the way to do both, ensuring the security of U.S. Navy operations while reducing the mortal hazard to some of the most majestic creatures on Earth. Our Navy will be the better for this, and so will the oceans our sailors defend.”

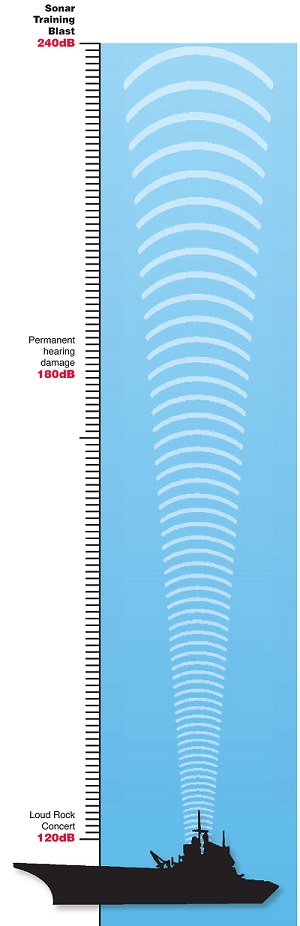

“If a whale or dolphin can’t hear, it can’t survive,” said David Henkin, an attorney for the national legal organization Earthjustice, who brought the initial challenge to the Navy’s latest round of training and testing on behalf of Conservation Council for Hawaii, the Animal Welfare Institute, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Ocean Mammal Institute. “We challenged the Navy’s plan because it would have unnecessarily harmed whales, dolphins and endangered marine mammals, with the Navy itself estimating that more than 2,000 animals would be killed or permanently injured. By agreeing to this settlement, the Navy acknowledges that it doesn’t need to train in every square inch of the ocean and that it can take reasonable steps to reduce the deadly toll of its activities.”

Scientific studies have documented the connection between high-intensity mid-frequency sounds, including Navy sonar, and serious impacts to marine mammals ranging from strandings and deaths to cessation of feeding and habitat avoidance and abandonment.

Until it expires in late 2018, the agreement will protect habitat for the most vulnerable marine mammal populations, including endangered blue whales for which waters off Southern California are a globally important feeding area; and numerous small, resident whale and dolphin populations off Hawaii, for which the islands are literally their only home.

Southern California and Hawaii represent two of the Navy’s most active ranges for mid-frequency sonar and explosives use.

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

Southern California provides some of the most important foraging areas anywhere on the globe for vulnerable species such as endangered blue and fin whales, and contains important habitat for small populations of beaked whales, a family of species that is considered acutely sensitive to naval active sonar, with documented injury and mortality.

“Numerous beaked whale strandings and deaths have been linked to naval uses of high-intensity sonar,” said Bill Rossiter, executive director for Advocacy, Science & Grants of Cetacean Society International. “Now, beaked whale populations in Southern California that have been suffering from the Navy’s use of sonar will be able to find areas of refuge where sonar will be off-limits.”

Key terms of the settlement applicable to Southern California include:

The Navy is prohibited from using mid-frequency active sonar for training and testing activities in important habitat for beaked whales between Santa Catalina Island and San Nicolas Island.

The Navy is prohibited from using mid-frequency active sonar for training and testing activities in important habitat for blue whales feeding near San Diego.

Navy surface vessels must use “extreme caution” and travel at a safe speed to minimize the risk of ship strikes in blue whale feeding habitat and migratory corridors for blue, fin and gray whales.

HAWAII

Hawaii represents an oasis for numerous, vulnerable populations of toothed whales, such as spinner dolphins, melon-headed whales and endangered false killer whales. Studies have shown that they are distinct from other populations in the tropical Pacific and even, in some cases, from populations associated with other islands, with only a few hundred individuals in existence. The Big Island of Hawaii and the Maui 4-Island Complex host many of these populations.

Key terms of the settlement applicable to Hawaii include:

The Navy is prohibited from using mid-frequency active sonar and explosives for training and testing activities on the eastern side of the Island of Hawaii and north of Moloka?i and Maui, protecting Hawaiian monk seals and numerous small resident populations of toothed whales including the endangered insular population of false killer whales and Cuvier’s beaked whales.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The Navy is prohibited from exceeding a set number of major training exercises in the channel between Maui and Hawaii Island and on the western side of Hawaii Island, limiting the number of times local populations will be subjected to the massive use of sonar and explosives associated with major training exercises.

Navy surface vessels must use “extreme caution” and travel at a safe speed to minimize the risk of ship strikes in humpback whale habitat.