Energy Transition Rethink

Europe’s headlong embrace of clean energy faces a reality check.

(Article originally published in Mar/Apr 2022 edition.)

“The best laid schemes o’mice an’ men / Gang aft a-gley,” wrote Scottish poet Robert Burns more than 200 years ago. He might just as well have been referring to the experience of the attendees at last fall’s Glasgow climate conference.

The juggernaut of climate activism ran into doubts over the science and encountered opposition to the proposed mandates for eliminating fossil fuels by governments suddenly confronting the realities of the energy transition. History has shown transitions to be tougher, longer and more economically disruptive and costly than anticipated.

This doesn’t mean the goal of eliminating carbon emissions and their environmentally damaging effects should be forsaken, but it suggests caution should be exercised.

What upset the energy transition momentum was the combination of poor performance from renewable energies, the high cost of backup power and the realization that fossil fuel dependence can put countries and populations at risk geopolitically. The power issue only emerged when countries that raced to abandon fossil fuels and repower their economies with intermittent energy sources – while lacking adequate backup capacity – suddenly found themselves vulnerable when electricity failed to arrive when needed. Moreover, they found that lacking backup power could prove extremely expensive, inflicting severe financial hardships on citizens.

The geopolitical risk in depending on unsavory fossil fuel suppliers became front and center with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Europe depends on Russia for 45 percent of its imported natural gas, a third of its oil and nearly half its coal. Reducing Russian gas dependency has been an issue in Belgium, home to the European Commission, for nearly 15 years – to no avail. Since 2010, Europe’s domestic gas production has declined. So even with stable gas consumption, imports have continued to increase and dependence on Russia has only grown.

Focal Point

Germany has been the focal point of the Russian gas dependency quandary because the country derives over 50 percent of its gas from Russia, helping power the largest economy on the continent. Germany also gets more than 30 percent of its oil and some coal from Russia.

Given the wars between Germany and Russia, including the partitioning of Berlin and the building of the infamous wall during the Cold War era, Germany’s foreign policy has evolved in recent times from antagonistic to a more dovish and patient one. Toleration of Russia’s aggressive geopolitical moves was accepted because Germans feared another military confrontation. Instead, Germany believed that greater commercial interaction would reduce Russia’s aggression.

That part of Germany’s diplomatic framework rested on Wandel durch Handel (“change through trade”), which meant doing business with Russia, and often significant business, to hopefully moderate Russia’s aggression, despite the invasions of European neighbors.

Buying energy and other raw materials from Russia was critical to Germany’s foreign trade policy. Even after the 2014 Russian takeover of Crimea, Germany willingly agreed to a second natural gas pipeline from Russia – Nord Stream 2 – championed by German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Nord Stream 2 was seen as an economic and political threat to Europe and NATO by the Trump Administration, which sanctioned the project as part of its effort to control Russia, only to have it receive a green light from the incoming Biden Administration.

When certified and in operation, it will further increase Germany’s dependence on Russian gas. The pipeline’s future now remains unclear following Germany’s new chancellor’s radical change to the country’s foreign, military and energy policies in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Turning Point

The German coalition government, headed by Chancellor Olaf Scholz, has strong representation from the Green party as well as other environmentally friendly members. In an emergency parliamentary meeting following the Russian invasion, Scholz shocked the world and his country by announcing a 180-degree turn in his nation’s foreign policy, including changes to its energy transition plans.

As the leading continental country pushing the climate change agenda, Germany was aggressively phasing out coal-fired power plants, building renewable energy sources, banning the sale of gasoline-powered vehicles and shutting down the nation’s nuclear plants. The latter policy had been put in place following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan. Capitalizing on the anti-nuclear views of Germans, Merkel used the accident to accelerate nuclear plant closures with the final ones to be shuttered this year.

Last year, despite the threat of a Russian-Ukraine conflict and stretches of windless and cloudy days limiting wind and solar power’s electricity contribution, Germany remained committed to its path for decarbonizing its economy. Europe’s 2020-2021 winter had been colder than normal, resulting in natural gas storage volumes being drawn down to critically low levels and elevating spot gas prices.

Those storage caverns would need to be refilled during the summer and fall, which further elevated spot gas prices. The refilling efforts ran headlong into energy market problems created by days of wind stillness and clouds blocking the sun. Electricity from renewable sources fell well below forecasted levels, forcing utilities to turn to backup power sources.

The lack of adequate backup power forced German utilities and others elsewhere in Europe to restart recently mothballed coal- and natural gas-fired power plants. European power companies were suddenly aggressively buying natural gas and coal supplies while trying to rebuild prior fossil fuel supply chains.

The result was record gas and coal spot prices, partly in response to Europe being the swing market for global coal and LNG supplies. As Europe’s gas demand exploded, its utilities bid up prices for spot LNG cargoes against Asian buyers who traditionally had been willing to pay higher prices. As gas prices spiraled upward, coal became competitively cheaper, adding to its demand.

“Living Through a Watershed Era”

Chancellor Scholz announced, “We are living through a watershed era,” adding “the world afterwards will no longer be the same as the world before.” Besides retaliatory actions against Russia and committing German troops to the NATO effort to limit the war, he committed €100 billion to beefing up military armaments, spending more than two percent of the nation’s GDP on defense and helping develop new, state-of-the-art weaponry.

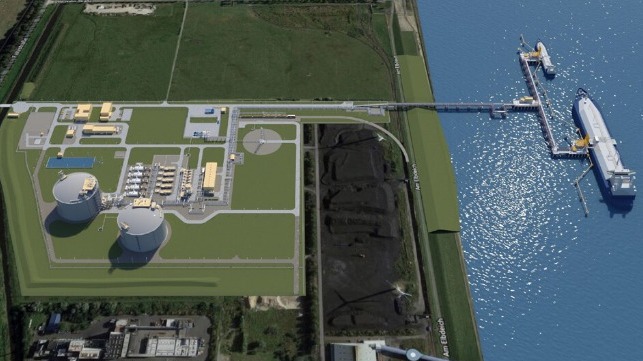

Recognizing fuel security concerns, Scholz stated, “And we will change course in order to eliminate our dependence on imports from individual energy suppliers.” He announced plans to boost natural gas and coal storage volumes and build two LNG import terminals, which will be capable of eventually importing hydrogen fuel.

The government is removing its energy surcharge on consumer bills supporting renewables, increasing the commuter tax allowance, providing a heating subsidy for low earners, energy subsidies for families and tax relief measures. These moves are to help citizens hurt by high fuel and electricity bills, thus preventing more from falling into energy poverty.

While these policy shifts caught the parliament and public by surprise, the greatest shock was among the Green party members of Scholz’s cabinet, who were forced to acknowledge why these actions were necessary. The reality is that the transition away from high dependence on Russian gas and oil will require years to effect and will prove costly.

Italy’s Ecological Transition Minister Roberto Cingolani recently told his Senate it will take at least three years for the country to completely replace its gas imports from Russia with other sources. Rome gets about 40 percent of its total gas imports from Russia. Cingolani said that Italy could replace two-thirds of its Russian imports with more gas from Algeria and increasing coal- and oil-fired power generation in the near to intermediate term. Long-term solutions require boosting LNG imports and bringing in more electricity from Northern Europe, but this will require four to five years to be realized.

In Belgium, the government extended by 10 years the operation of two nuclear plants because of the gas supply crisis and will build two new gas-fired plants. France, too, is going ahead with more nuclear plants to augment their already high electricity generation share.

Other countries in Europe are reassessing their energy transition plans as fuel sources to back up growing renewable energy capacities have lagged. These transition reassessments are confronting the reality that global LNG output will only grow about five percent this year. Countries wanting more LNG must bid up for supply or commit to long-term contracts to support new export terminals.

The International Energy Agency waded in with a 10-point plan for dealing with the energy supply crisis. It recommends people turn down thermostats, work from home and drive less. Many people have embraced these actions to manage high electricity, heating and transportation bills. Yet German transportation data shows traffic on the autobahns remains high and drivers have not slowed to conserve fuel. Oh, and did we mention Tesla just boosting the price of its cars by five percent to offset the rising cost of raw materials used in the batteries for these electric vehicles?

Reality Check

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The realities of the energy transition underway are shocking the idealists who neither see nor saw the technical challenges associated with their plans. Intermittent renewable energy without backup power produces electricity blackouts and debilitating costs borne by the public.

Past energy transitions have been shown to take long times. Better planning and implementation would mitigate the economic and financial harm inflicted on people. We can still have adequate, affordable and cleaner energy.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.