1916: The Greatest Boat Journey Ever Made

In 1914, Ernest Shackleton set out to cross Antarctica on foot from the Weddell to the Ross Sea. However, his ship Endurance got trapped in pack ice on the Weddell Sea and was slowly crushed, just one day short of her destination.

Shackleton and his men became castaways in one of the most hostile environments on earth, and their quest for survival led to what has been called one of the greatest boat journeys ever made. The journey began 100 years ago, on April 24.

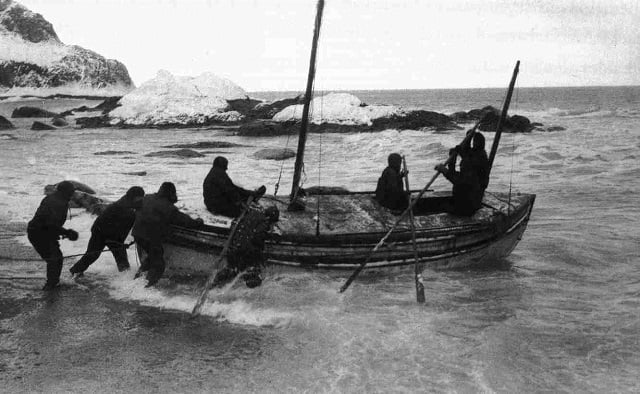

After Endurance became trapped, her 56-man crew survived as castaways on the ice for five months. Shackleton eventually led them to Elephant Island about 180 miles away, and on April 24, 1916, Shackleton and five of his toughest and best sailors (Frank Worsley, Thomas Crean, Henry McNish, Timothy McCarthy, and John Vincent) set sail in the largest lifeboat, the 22-foot James Caird, to the whaling stations of South Georgia, over 800 miles away.

After Endurance became trapped, her 56-man crew survived as castaways on the ice for five months. Shackleton eventually led them to Elephant Island about 180 miles away, and on April 24, 1916, Shackleton and five of his toughest and best sailors (Frank Worsley, Thomas Crean, Henry McNish, Timothy McCarthy, and John Vincent) set sail in the largest lifeboat, the 22-foot James Caird, to the whaling stations of South Georgia, over 800 miles away.

One the ice, the men set up a makeshift camp. Their five tents were made of linen so thin the moon could be seen through them. They had no communication with the rest of the world, and the temperature ranged from highs in the 30s to a low of -21 degrees Fahrenheit.

Along with the three life boats, three tons of food supplies were salvaged from the half-sunk Endurance, and when these ran out the men existed on penguins and seals. Shackleton made two attempts to march to land hauling the lifeboats and food. Their dogs pulled the sledges loaded with food, but the men had difficulty hauling the lifeboats, weighing approximately one ton each over the uneven ice.

Along with the three life boats, three tons of food supplies were salvaged from the half-sunk Endurance, and when these ran out the men existed on penguins and seals. Shackleton made two attempts to march to land hauling the lifeboats and food. Their dogs pulled the sledges loaded with food, but the men had difficulty hauling the lifeboats, weighing approximately one ton each over the uneven ice.

When the ice was so thin that the men could feel the swell of the ocean beneath their feet, they manned the lifeboats and set sail for Elephant Island, some 100 miles to the North. At the end of March 1916, the last of their beloved sled dogs were shot and eaten, and Shackleton made the decision to split the crew.

Knowing that the risks were extreme, Shackleton and his five men set out in the James Caird to cross 800 miles of the roughest seas on earth. Their goal was the whaling stations on the east side of South Georgia Island. Guided only by sextant and compass, and limited by continuously overcast skies, they risked missing the island and heading into the open ocean.

The boat, which pitched and rolled in the heavy seas, and Worsely was held steady by two shipmates while he took sightings. The horizon was also necessary for a position calculation and had to be estimated due to the large swell. Over the 17 day voyage, Worsely was only able to take four sightings. Pounded by wind and waves, he sat in the bottom of the boat with his nautical almanac to make the necessary calculations.

On May 10, 1916, the James Caird, beginning to fall apart, landed on South Georgia Island. Shackleton was forced to land on the west side of the island, and with frostbitten feet, he, Crean and Worsely set out over the mountains to find help 22 miles away.

On May 10, 1916, the James Caird, beginning to fall apart, landed on South Georgia Island. Shackleton was forced to land on the west side of the island, and with frostbitten feet, he, Crean and Worsely set out over the mountains to find help 22 miles away.

They had a compass and a little bit of food and used screws from the James Caird in the soles of their boots for traction. They reached the whaling station and immediately began planning the rescue of the men left behind on Elephant Island. Over the next three months Shackleton made numerous attempts to reach them.

Finally, with the help of the Chilean tug Yelcho, Shackleton was able to reach them. Miraculously, after two years and against impossible odds, all of the crew of the Endurance were rescued.

Ernest Shackleton 1874-1922 (Source: American Museum of Natural History)

.jpg) Ernest Shackleton was born on February 15 1874 in Ireland. His father wanted him to study medicine, but at the age of sixteen he went to sea, and by twenty-four had qualified to command a British ship anywhere on the seven seas. Shackleton made four voyages to Antarctica, the first as a member of Captain Robert F. Scott's expedition of 1901-1903.

Ernest Shackleton was born on February 15 1874 in Ireland. His father wanted him to study medicine, but at the age of sixteen he went to sea, and by twenty-four had qualified to command a British ship anywhere on the seven seas. Shackleton made four voyages to Antarctica, the first as a member of Captain Robert F. Scott's expedition of 1901-1903.

Shackleton put this valuable experience to use in 1907, when he led his own Antarctic expedition. It got within ninety-seven miles of the South Pole and conducted much valuable scientific research; the explorers climbed Mt. Erebus and located the south magnetic pole. Upon his return in 1909, Shackleton was knighted.

In 1914, the explorer set out again. Since Amundsen had already reached the South Pole, Shackleton planned to cross the continent from one sea to the other, a 2,000-mile (3,200-km) journey of great scientific as well as historic importance. One day's sail away from the continent, his specially constructed ship, the Endurance, was trapped in pack ice; 281 days later, crushed, the boat sank.

In 1921 Shackleton led a final expedition southward to explore Enderby Land, but he died near the outset and was buried on South Georgia.

Shackleton is remembered as perhaps the greatest of the Antarctic explorers, less for his achievements than for his unfaltering leadership and courage under unthinkably gruelling circumstances.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.