Why Your Recycled Plastic May End Up in the Ocean

[By Monique Retamal, Elsa Dominish, Nick Florin and Rachael Wakefield-Rann]

We all know it’s wrong to toss your rubbish into the ocean or another natural place. But it might surprise you to learn some plastic waste ends up in the environment, even when we thought it was being recycled.

Our study, published today, investigated how the global plastic waste trade contributes to marine pollution.

We found plastic waste most commonly leaks into the environment at the country to which it’s shipped. Plastics which are of low value to recyclers, such as lids and polystyrene foam containers, are most likely to end up polluting the environment.

The export of unsorted plastic waste from Australia is being phased out – and this will help address the problem. But there’s a long way to go before our plastic is recycled in a way that does not harm nature.

Know your plastics

Plastic waste collected for recycling is often sold for reprocessing in Asia. There, the plastics are sorted, washed, chopped, melted and turned into flakes or pellets. These can be sold to manufacturers to create new products.

The global recycled plastics market is dominated by two major plastic types:

- polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which in 2017 comprised 55 percent of the recyclable plastics market. It’s used in beverage bottles and takeaway food containers and features a “1” on the packaging

- high-density polyethylene (HDPE), which comprises about 33 percent of the recyclable plastics market. HDPE is used to create pipes and packaging such as milk and shampoo bottles, and is identified by a “2."

- The next two most commonly traded types of plastics, each with four percent of the market, are:

- polypropylene or “5,” used in containers for yoghurt and spreads

- low-density polyethylene known as “4,” used in clear plastic films on packaging.

The remaining plastic types comprise polyvinyl chloride (3), polystyrene (6), other mixed plastics (7), unmarked plastics and “composites”. Composite plastic packaging is made from several materials not easily separated, such as long-life milk containers with layers of foil, plastic and paper.

This final group of plastics is not generally sought after as a raw material in manufacturing, so has little value to recyclers.

Shifting plastic tides

China banned the import of plastic waste in January 2018 to prevent the receipt of low-value plastics and to stimulate the domestic recycling industry.

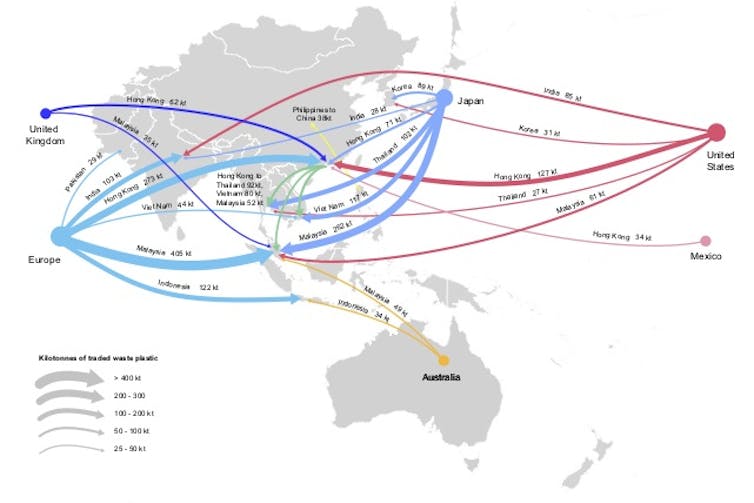

Following the bans, the global plastic waste trade shifted towards Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The largest exporters of waste plastics in 2019 were Europe, Japan and the US. Australia exported plastics primarily to Malaysia and Indonesia.

Australia’s waste export ban recently became law. From July this year, only plastics sorted into single resin types can be exported; mixed plastic bales cannot. From July next year, plastics must be sorted, cleaned and turned into flakes or pellets to be exported.

This may help address the problem of recyclables becoming marine pollution. But it will require a significant expansion of Australian plastic reprocessing capacity.

Map showing the import and export map of plastic waste globally. Authors provided

What we found

Our study was funded by Australia's federal Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. It involved interviews with trade experts, consultants, academics, NGOs and recyclers (in Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand) and an extensive review of existing research.

We found when it comes to the international plastic trade, plastics most often leak into the environment at the destination country, rather than at the country of origin or in transit. Low-value or “residual” plastics – those left over after more valuable plastic is recovered for recycling – are most likely to end up as pollution. So how does this happen?

In Southeast Asia, often only registered recyclers are allowed to import plastic waste. But due to high volumes, registered recyclers typically on-sell plastic bales to informal processors.

Interviewees said when plastic types were considered low value, informal processors frequently dumped them at uncontrolled landfills or into waterways. Sometimes the waste is burned.

Plastics stockpiled outdoors can be blown into the environment, including the ocean. Burning the plastic releases toxic smoke, causing harm to human health and the environment.

Interviewees also said when informal processing facilities wash plastics, small pieces end up in wastewater, which is discharged directly into waterways, and ultimately, the ocean.

However, interviewees from Southeast Asia said their own domestic waste management was a greater source of ocean pollution.

A market failure

The price of many recycled plastics has crashed in recent years due to oversupply, import restrictions and falling oil prices, (amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic). However clean bales of PET and HDPE are still in demand.

In Australia, material recovery facilities currently sort PET and HDPE into separate bales. But small contaminants of other materials (such as caps and plastic labels) remain, making it harder to recycle into high quality new products.

Before the price of many recycled plastics dropped, Australia baled and traded all other resin types together as “mixed plastics”. But the price for mixed plastics has fallen to zero and they’re now largely stockpiled or landfilled in Australia.

Several Australian facilities are, however, investing in technology to sort polypropylene so it can be recovered for recycling.

Doing plastics differently

Exporting countries can help reduce the flow of plastics to the ocean by better managing trade practices. This might include:

- improving collection and sorting in export countries

- checking destination processing and monitoring

- checking plastic shipments at export and import

- improving accountability for shipments.

But this won’t be enough. The complexities involved in the global recycling trade mean we must rethink packaging design. That means using fewer low-value plastic and composites, or better yet, replacing single-use plastic packaging with reusable options.

The authors would like to acknowledge research contributions from Asia Pacific Waste Consultants (APWC) - Dr Amardeep Wander, Jack Whelan and Anne Prince, as well as Phil Manners at CIE.

Monique Retamal is Research Principal, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

Elsa Dominish is a Senior Research Consultant, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

Nick Florin is Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

Rachael Wakefield-Rann is a Research Consultant, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

This article appears courtesy of The Conversation and may be found in its original form here.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.