Why the New Package of Sanctions on Russia is a Game-Changer for Europe

On June 25, in the wake of the Russian oil price cap and the failed Wagner Group revolt, the EU announced its new “11th sanctions package." As the war rages on, it is clear that the EU has decided to intensify reactionary efforts, specifically focusing on shipping and transport as key areas of interest.

However, context is important in understanding these recent EU decisions. For decades, the EU had no ‘biting’ sanctions policy, trailing behind the leadership of the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC). OFAC’s sanctions peaked under President Donald Trump, tied to fears of a decoupled, bi-polar world of trade – Russia, China, and Iran on one side, and the West on the other. In efforts to keep up, the UK created the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI), but European efforts still lagged behind.

Now in 2023, the EU is stepping up in the world of sanctions. 90 percent of the world’s trade is transported via ocean shipping, a crucial artery of trade – and unfortunately, still one of the least governed supply chains. In 2020, both OFAC and OFSI adopted the UN Security Council definition of Deceptive Shipping Practices (DSPs), establishing clear regulations to tackle maritime shipping of sanctioned goods.

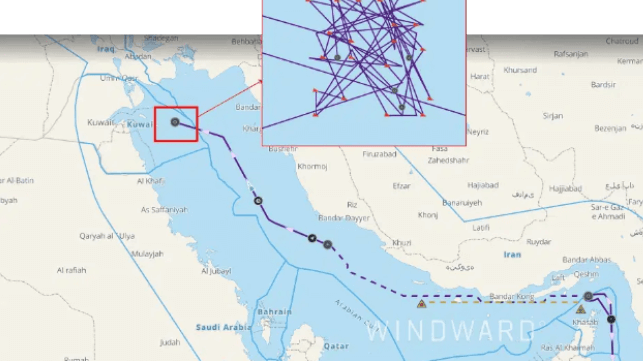

But bad actors always innovate faster than regulators, and a new DSP has emerged – AIS spoofing. Historically, the focus has been on “dark activities” – when vessels turn off their location transponders – and “identity manipulation” – adopting a fake identity. Now, the industry must confront AIS spoofing, a DSP encompassing multiple new deceptive shipping practices - most notably location (GNSS) manipulation, during which vessels transmit a fake location.

Both OFAC and OFSI have yet to update the requirements, opening a loophole whereby bad actors – led by Russia – can trade sanctioned goods above price caps. Now, the EU is stepping up, and for good reason. Data showed a 12% increase in location (GNSS) manipulation during H1 2023 compared to last year and an 82% increase over H1 2021, highlighting that the technique has become common practice. Data also shows a 50% uptick in the size of dark fleets between January and June 2023 and a 15% increase in gray fleet size in the last quarter.

Now, for the first time, regulators can directly connect entry of a port or a channel with deceptive shipping practices, and specifically spoofing. This gives authorities the power to block entries – a powerful, fast, and public sanction on players in the dark fleet, the gray fleet, or those trading above G7 price caps.

It’s clear that this regulation gives authorities more teeth, but what does it mean in practice?

By July 24th, port authorities, traders, shipping companies, pilotage service providers and even bunker suppliers, are expected to go beyond mere sanctions-list screening. This requires automated alerts for deceptive practices, with full visibility and detection capabilities for every milestone of a vessel’s journey. Failure to keep up could lead to sanctions breaches, reputational harm, and other penalties.

More specifically, there will now be a port and locks access ban for vessels turning off, manipulating, or spoofing their location and for vessels conducting ship-to-ship transfers when suspected of violating Russian oil restrictions. Tankers engaging in ship-to-ship oil transfers will need to provide 48-hour notice within the EEZ of any EU country.

Furthermore, the regulations also prohibit transit of goods and technology via Russian territory and waters, which might contribute to Russia’s defense and security sector. Accordingly, cargo owners, BCOs, importers, exporters and forwarders operating on their behalf will now be dealing with a world of trade compliance which they haven’t been a part of. When these entities book shipments through a liner, they aren’t in control of the container route, but the onus will now be on them to effectively monitor and control their supply chain.

To implement these provisions, the European Commission, with the assistance of the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA), must support the competent authorities through, inter alia, the monitoring of suspicious ship-to-ship transfers, incidents of illegal interference with vessels’ AIS, and the exchange of information based on the Union Maritime Information and Exchange System (SafeSeaNet).

The issue is that SafeSeaNet wasn't built for this purpose. It’s a safety system, which the EU now expects to enable sanctions enforcement. Those trading above the price cap have become significantly more sophisticated so it is unlikely that SafeSeaNet can provide effective monitoring and enforcement of these regulations.

On the brighter side, not everyone has to abide by the regulations for them to be effective. Enforcement in key areas may be enough. Hamburg, Antwerp, and Brussels are all hubs for fueling and replenishment, and if enforcement is focused there, sanctions will have a deeper bite and a wider impact on every vessel - regardless of whether its own flag country or local regime is interested in enforcing this.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

If indeed the EU can walk the walk, trade flows will change once again, and a new chapter of global trade will unfold before our eyes.

Ami Daniel is the co-founder and CEO of Windward, a global leader in maritime risk analytics.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.