Web Site Security for Seaports and Shipping Lines

All of us use the Web and have typed in the now-familiar http:// prior to the address of a Web site. And most of us don't think too much about what that means. Sometimes we see a little lock icon in the browser's address bar and don't think too much about that, either, although we have a vague sense that this site is more secure than a site without a lock.

Here are some of the basics of what this all means. HTTP stands for the Hypertext Transfer Protocol, which is the data communications protocol (i.e., language) that allows our Web browser to communicate with a Web server. Developed in 1990, before the Internet became public and commercialized, HTTP was not designed with security in mind.

Electronic commerce refers to buying and selling items online. The first Internet e-commerce site that accepted credit cards appeared in 1992, although the concept of e-commerce predates today's Internet. One impediment to large-scale commerce on the Internet was that most people did not feel comfortable providing credit card and other personal information online. As a response, Netscape introduced the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol in 1995 to encrypt browser-to-server communication. HTTP used in conjunction with SSL is referred to as HTTPS.

Given this historical background, one might assume that HTTPS only has applicability for building secure, commerce-related Web sites. Even if your site is not handling commercial transactions, there might be information about your users – e.g., names, e-mail addresses, and other contact information – that can be appropriated by hackers from an unprotected HTTP site. Indeed, an intruder can learn a lot about your business and customers merely by monitoring your site's traffic and aggregating small amounts of information in order to learn the big picture.

HTTPS proves two things about a Web site: authenticity (i.e., this is the true, intended site) and integrity (i.e., these are the true, unmodified pages at the site). HTTPS-protected sites prevent a third-party from injecting intrusive messages such as advertisements that not only ruin the user's experience at your Web site but might also inadvertently trick a user into providing personal information. A protected site prevents a third-party from inserting malicious software (malware), spyware, cookies, scripts, or other exploitable objects into your Web site. Furthermore, use of HTTPS prevents a third-party from creating a bogus, spoofed version of your Web site in order to steal user information via a man-in-the-middle attack.

And, of course, HTTPS encryption protects the communication between the user and the Web site, including the exchange of sensitive customer information such as credit cards, addresses, and other personal identifying information. With HTTPS, intruders can neither passively read information exchanged nor insert bogus messages. And if this is not enough, most search engines show a slight preference to an HTTPS site over an HTTP site.

The use of HTTPS on Web sites has expanded tremendously over the last few years for all of the reasons mentioned above. Firefox, in fact, estimates that more than 60% of Web pages today are posted at HTTPS sites.

Figure 1. An HTTPS site is indicated by the lock icon and https:// appearing in the address bar.

As a user, it is straightforward to know when a site uses HTTPS by looking for a lock icon and the https:// in the address bar (Figure 1). Be careful, however; some bogus Web sites will put a lock icon on the browser tab or within the page itself. You want to see the lock in the address bar.

Figure 2. A popup like this will occur when you click on the lock.

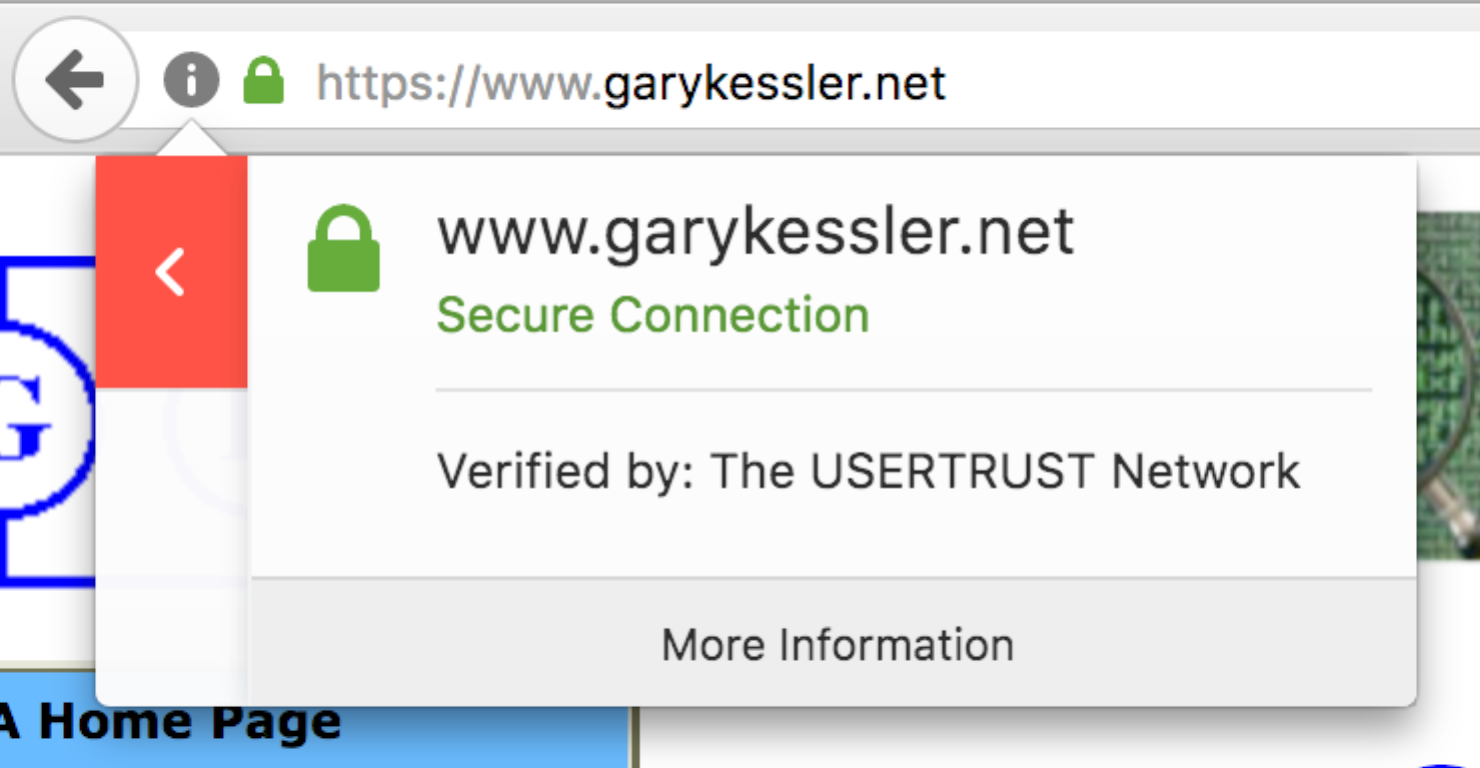

Figure 3. Additional information about the SSL details can also be found in the popup message.

The lock icon is actually the pathway to additional information about the security of a site. If you click on the lock, a small message will appear confirming that the site is secure (Figure 2). If you click on the right-arrow of the pop-up, you can find additional information, including a link to the details about the SSL protections (Figure 3).

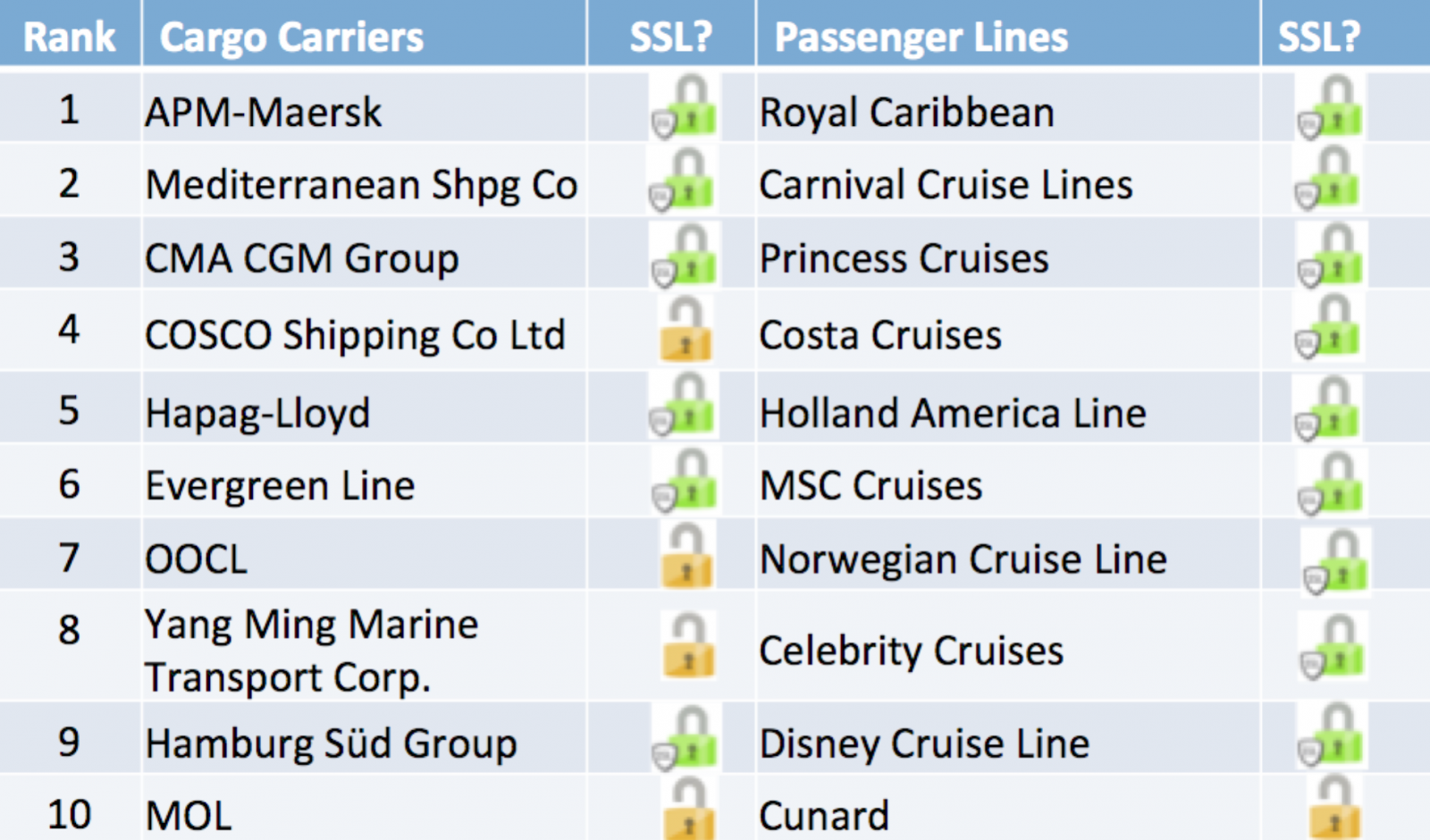

Figure 4. Use of HTTPS by the primary Web site of the 10 largest cargo and passenger lines. (The green lock with the shield indicates HTTPS and the yellow "unlock" indicates HTTP.)

Given this information, how does the maritime industry stack up? A review of 40 Web sites representing the largest cargo and passenger ports, and cargo and passenger shipping lines found one of the cargo ports, two of passenger ports, six of cargo lines, and nine of the passenger lines used HTTPS to protect their Web sites.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

This is an important finding, particularly as ports are one of America's biggest economic vulnerabilities. Passenger and shipping information, customer information, manifests, company proprietary data, financial information, and much more are at risk. While the shipping lines appear to do a better job at protecting the integrity of their Web sites, we see this as a call to arms that much more can be done. Remember that intruders will attack every exploitable attack vector and they start their reconnaissance at your Web site.

Gary C. Kessler, Ph.D., CISSP is a professor of cybersecurity at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (ERAU) in Daytona Beach, holds a USCG MMC, and is a cybersecurity and digital forensics consultant and educator. More information can be found at https://garykessler.net. Cameron Benton, a homeland security and cybersecurity student at ERAU, assisted in the data gathering for this article.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.