Vanuatu Illustrates Risks of Thin Subsea Cable Infrastructure

A single point of failure for connectivity is a common vulnerability across the Pacific

[By Cynthia Mehboob]

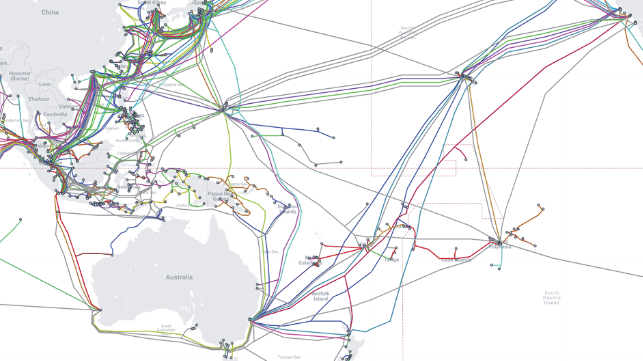

Last month’s magnitude 7.3 earthquake near Vanuatu caused widespread devastation and left at least a dozen people dead. The disaster also exposed a critical vulnerability in Vanuatu’s digital infrastructure, specifically the over-reliance on a single undersea cable, ICN1. A fire at the cable landing station temporarily interrupted the power supply, disabling internet traffic. The connection was restored 10 days later, after what was described as “a multilateral effort under extreme conditions”.

Vanuatu’s heavy dependence on a single point of failure for its connectivity was not a surprise. The 2022 volcanic eruption in Tonga, which similarly disrupted communications across the Pacific, raised concerns about the need for redundancy in submarine cable systems. Despite this, securing funding for additional cables in Vanuatu is an uphill battle.

The Vanuatu government has long recognised the importance of diversifying its digital infrastructure, yet progress remains slow. Since 2018, the government has advocated for a second cable. The challenge lies in financing. A new cable would require substantial capital and maintaining it could raise telecommunications prices for Vanuatu’s already vulnerable population. Hence, Vanuatu requires funding for new cable infrastructure alongside financial commitment from external development partners to pay for the operational costs.

This difficulty is not unique to Vanuatu. Western governments, including Australia and the United States, have acknowledged the need for increased investment in submarine cable infrastructure across the Pacific, including Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. These countries are seen as strategically important in the face of rising Chinese influence in the region. Yet, despite this recognition, the funding for second cables remains elusive. With competing priorities – healthcare, education, and transport – Pacific governments often struggle to allocate the necessary resources.

With the government faced with financial difficulties, the private sector is providing connectivity solutions.However, geopolitical competition has posed challenges for Vanuatu's submarine cable sector since at least 2018. At that time, Simon Fletcher, CEO of The Interchange Group – a Vanuatu-based consortium rolling out the nation’s internet cables – stated that Australia’s intervention in the Solomon Islands Coral Sea Cable project had adversely impacted its privately funded projects. Fletcher tweeted that it was “very hard to compete with a free cable”.

Despite the challenges, Interchange Limited is implementing the TAMTAM system, the world’s first Science Monitoring and Reliable Telecommunications (SMART) cable set to connect Vanuatu to New Caledonia, a project contracted to Alcatel Submarine Networks. Meanwhile, Google has proposed a third cable connecting Vanuatu to the broader Pacific network.

However, until these projects are completed, Vanuatu lies exposed.

Satellite solutions often considered the fallback for cable outages, offer limited relief in Vanuatu. Geostationary (GEO) satellites, used historically for island communications before any cable, have reduced bandwidth and high operational costs, so are typically reserved for critical services such as government, airlines, banking and healthcare. During major outages, commercial services such as social media and entertainment are sacrificed. As a result, the country remains heavily dependent on its sole undersea cable.

The arrival of low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites such as Starlink has introduced new possibilities. Starlink’s higher bandwidth and lower cost make it an attractive alternative for countries such as Vanuatu. Yet not without complex policy questions.

Starlink offers direct-to-consumer broadband, bypassing traditional telecom providers and disrupting local markets. Additionally, the dual-use nature of Starlink – serving both civilian and military purposes – raises significant security and legal concerns. In light of its involvement in conflicts like the war in Ukraine, questions emerge over whether Starlink could be considered a legitimate target under international law, especially if its services become integral to military operations. This concern extends to countries relying on Starlink for resilience during undersea cable outages, where the line between civilian and military use becomes increasingly blurred.

Furthermore, while Starlink may be useful as a backup in times of crisis, it cannot replace the capacity and reliability of submarine cables. The service is finite, with bandwidth limitations that could lead to congestion, particularly in densely populated regions where demand for high-speed internet is growing. Unlike cables, which offer scalable infrastructure, Starlink’s network is constrained by the number of satellites in orbit and the number of users accessing the system at any one time. As Vanuatu’s digital economy grows, a satellite network may provide insufficient capacity when it is needed most.

The case for a second submarine cable in Vanuatu is clear. Satellite systems, while effective for temporary outages, cannot provide the high-capacity, low-latency connectivity that a robust undersea cable offers.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Cynthia Mehboob is a PhD Scholar based at the Department of International Relations at the Australian National University. Her research interrogates the international security politics of submarine cables in the Indo-Pacific region.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter and is reproduced in abbrebiated form. The original may be found here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.