Russia Begins Fueling its Floating Nuclear Power Plant

Technicians in Northwest Russia have begun to load the reactors of the Akademik Lomonosov, Russia’s first waterborne nuclear power plant, with their uranium fuel in preparation for its journey to the Far East.

In a release, Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation, confirmed that the fueling operation is underway at Atomflot, the headquarters of the country’s nuclear icebreaker fleet in Murmansk. According to the release, loading of the floating plant’s first reactor began last week, with the second soon to follow.

Following the fueling, the two icebreaker-style KLT-40 reactors are expected to undergo a variety of tests in the Barents Sea before the barge is towed east through the Arctic to the Pacific port of Pevek in Chukotka. Once there, Rosatom says it will supply power for 100,000 residents and replace energy produced by the Bilibino Nuclear Power Plant, which will subsequently be decommissioned. Rosatom also expects the plant to power a number of offshore oil platforms in the Arctic.

The fueling operation is drawing international attention. Environmental groups have dubbed the plant a “nuclear Titanic” and a “floating Chernobyl,” and international media have been drawn to the novelty of a seafaring nuclear power station on which Russia has lavished millions of dollars and spent more a dozen troubled years building. The Akademik Lomonosov is the only plant of its kind in the world, and Rosatom has boldly promised more.

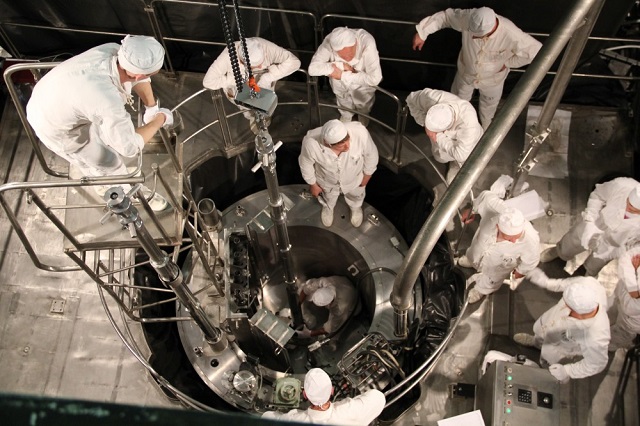

Technicians loading the first reactor aboard the Akademik Lomonosov, Russia's floating nuclear power plant. Credit: Rosenergoatom

As a result of all this international curiosity, suggests Andrei Zolotkov, an expert with Bellona in Murmansk, this week’s fueling operations will be carried out with special care. But much of the project has been shrouded in secrecy until recently. For years Rosatom has been less than forthright about the details of its construction and for years neglected to inform the public about exactly where the plant would be loaded with its nuclear fuel.

During the years of its construction, it was assumed that Rosatom would load the plant with its uranium directly at the Baltic Shipyard – located in the midst of a city of five million people, and just kilometers from tourist meccas like St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum, a notion that drew fire from many local politicians and perturbed Russia’s Baltic neighbors.

Intervention from Norway’s foreign ministry, spurred by Bellona, secured a promise from Rosatom not to fuel the nuclear barge until it had been towed past the coasts of Scandinavia. Yet even after this overture, Rosatom continued to keep the plant under wraps, once scrubbing a tour for independent nuclear experts, including Bellona’s Alexander Nikitin, who had been invited to take a peek under its hood.

Apparently cowed by the worldwide media frenzy over the Akademik Lomonosov’s launch in April, Rosatom lifted the veil slightly, allowing Nils Bøhmer, Bellona’s general manager, a closer look at the plant as it was towed past Norway’s western coast from a boat drawn up beside it.

Ever since, Vitaly Truntev, who oversaw the build of the floating plant for Rosatom, has promised to be more transparent about its progress toward its destination in the Far East, and it was in his name that the statement confirming the fueling was released.

Still, the new openness has done little to settle Bellona’s central concerns about Rosatom’s long range intentions for the floating nuclear power plant. By design, the plant is meant to operate in remote operations. But this very remoteness, Bellona has said, would vastly complicate the rescue operations that would be necessary after an accident, as well as the more routine clearing of spent nuclear fuel from its reactors.

Likewise, the visions of Fukushima’s waterlogged reactors have not faded from public memory, and the thought of a nuclear power plant as vulnerable to tsunamis and foul weather as is the ocean-based Akademik Lomonosov strikes an anxious chord among environmentalists.

Still, both Zolotkov and Nikitin have seen little reason to be concerned about the fueling operation itself. Because the Akademik Lomonosov’s reactors mimic those aboard their icebreaking cousins, the loading procedure should be routine for technicians at Atomflot, who have safely carried out similar operations for decades.

The public in Murmansk, as the Independent Barents Observer reports, is equally unfazed by the fueling, which it views as another ordinary undertaking carried out by the local nuclear industry.

But the notion of more floating plants reaching serial production in Russian shipbuilding yards is a worrying prospect for environmentalists. For the years of the plant’s construction, Rosatom touted the Akademik Lomonosov as a quick and easy energy solution for any country with a port.

Perhaps some solace can be found in the Akademik Lomonsov’s protracted and difficult birth. The keel for the plant was laid at the Sevmash shipyard near Severodvinsk in 2006, but the vessel was then moved to the Baltic Shipyard in 2008.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

After arriving there, it was lashed by lawsuits, bankruptcy proceedings, property disputes, occasional labor disagreements, budget shortfalls and regular but prolonged delays. When it finally arrives in Pevek, which it is expected to do in 2019, it will be a decade behind schedule at a price-tag of $480 million – nearly twice what Rosatom initially thought it would cost.

Source: Bellona

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.