China’s DF-27 Missile: Threatening Pacific Ships and the U.S. Homeland

By becoming the first major anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) power, China has dramatically changed the naval balance in the Western Pacific

Among the 2025 Pentagon report’s greatest revelations, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has fielded a conventional intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) able to range parts of America’s homeland. This makes China the first nation publicly assessed to have fielded an operational, conventionally-armed ICBM—the DF-27—albeit at the low end of the ICBM range band and with variant-dependent roles. America’s homeland is not a sanctuary from either PRC nuclear or conventional missiles.

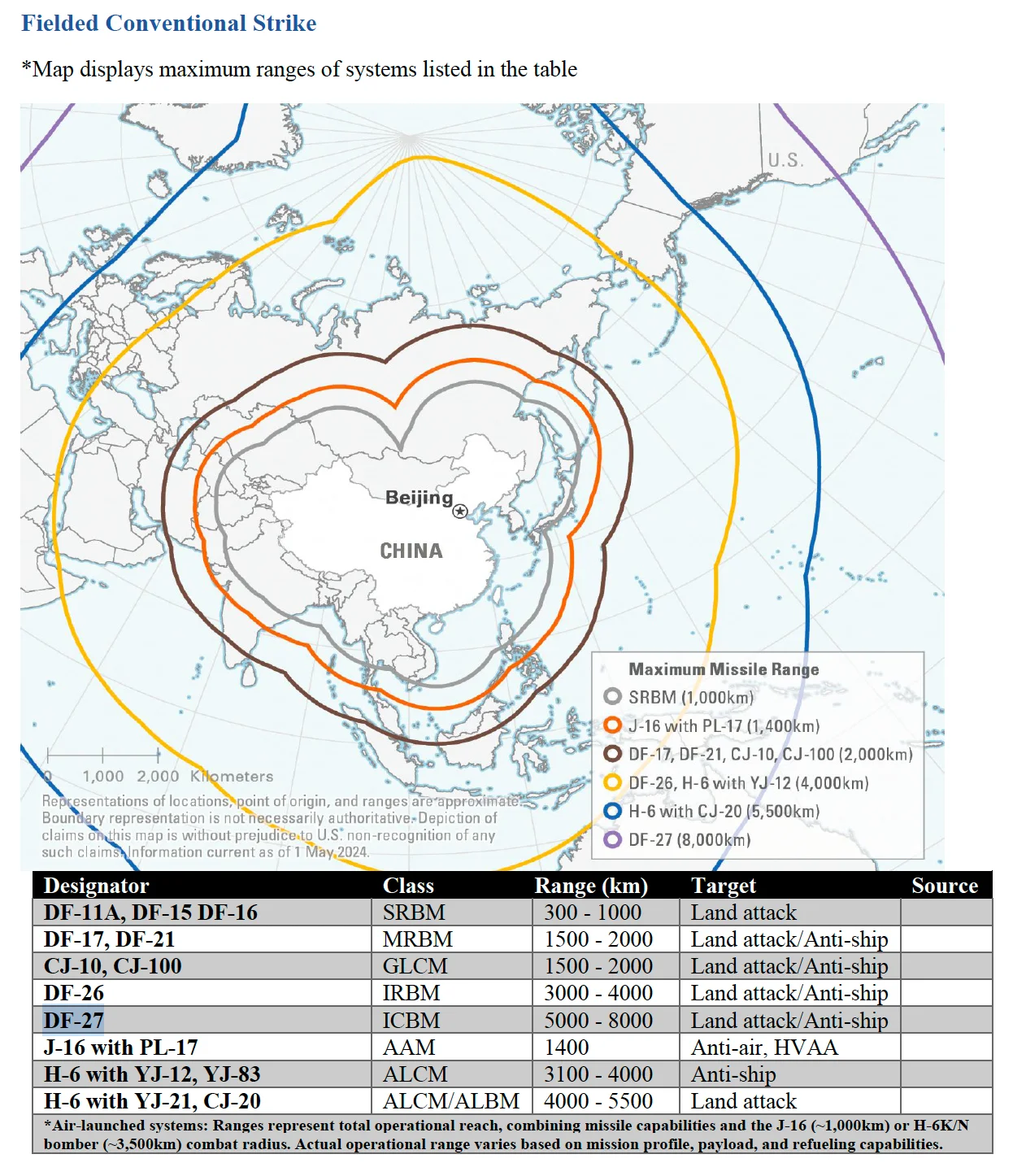

The report’s “Fielded Conventional Strike” figure (p. 85, reproduced above) identifies the DF-27 as a conventional ICBM with an estimated 5,000–8,000-km range, and denotes an anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) variant.

The DF-27’s 8,000-km maximum-stated range covers not only Alaska and Hawaii but also parts of the continental United States (CONUS). Like China’s shorter-range DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) families—which have both land-attack and anti-ship variants—and the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) MRBM family, the DF-27 family now includes both land-attack and anti-ship configurations. Anti-ship targeting capabilities thus make at least one variant of each of these four ballistic-missile families an ASBM.

As the Pentagon’s 2024 report explained, for example, “The PRC’s deployment of the DF-17 HGV-armed MRBM will continue to transform the [People’s Liberation Army] PLA’s missile force. The system, which was fielded in 2020, may replace some older [short-range ballistic missile] SRBM units and be used to strike foreign military bases and fleets in the Western Pacific.”

This year’s report is the first to explicitly confirm the DF-27’s deployment, status as an ICBM, and inclusion of an ASBM variant. Earlier U.S. assessments classified the DF-27’s range class as straddling the IRBM-ICBM boundary. The Pentagon’s 2021 and 2022 reports mentioned a “long-range” DF-27 ballistic missile in development. “Official PRC writings indicates [sic] this range-class spans 5,000-8,000km,” the 2022 report elaborated, with similar wording in 2023. The 2024 report (p. 89) stated that “The DF-27 may have an HGV [hypersonic glide vehicle] payload option in addition to conventional land-attack, conventional antiship, and nuclear payloads. The PRC probably is developing additional advanced nuclear delivery systems, such as a strategic HGV and a FOB [fractional orbital bombardment] system.”

These developments bespeak larger dynamics of tremendous importance. Conventional ballistic missiles have been a priority for China since its strategic rocket force—known as the Second Artillery Force from its establishment in 1966 until its redesignation as the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) at the end of 2015—began building a conventional missile component in the early 1990s, in the wake of PLA reassessments prompted by U.S. precision-strike performance in the 1990–91 Gulf War. Beijing stood up the core of what became its first conventional ballistic-missile brigade (equipped with the DF-15 short-range ballistic missile/SRBM) in 1991 and subsequently formally commissioned the brigade in 1993, at the same time that the Second Artillery was formally assigned a conventional strike mission.

With Washington and Moscow self-constrained by their bilateral 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty—which banned both nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles, their launchers, and related support infrastructure with ranges of 500–5,500 km—Beijing built the world’s largest arsenal of conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles in precisely that range band, with conventional ballistic missiles outnumbering nuclear ballistic missiles many fold (on the order of seven-to-one, by some estimates).

China today has the world’s most active and diverse ballistic missile development program, rapidly producing and fielding purpose-built systems at staggering scope and scale. With the world’s largest organizational system for acquiring and applying technology by all means possible, as well as the world’s largest defense industrial base by key measures, Beijing is able to translate doctrine into deployment with remarkable speed.

The DF-27 is a case in point. In 2020, PLA National Defense University’s new edition of Science of Military Strategy, a textbook for senior officers, observed in typical oblique fashion that “conventional strategic missiles that have the ability for rapid global precision attacks will become an important component of major military powers’ strategic missile strengths.” Always determined to be a major military power in every way possible, less than five years later China became the first to field an analogous capability: a conventional ICBM—with an ASBM variant—that can conduct rapid, long-range precision strikes out to intercontinental distances, including against its “strong enemy’s” homeland and its naval forces at sea.

Continuing a multi-year assessment, the Pentagon’s 2025 report judges that “China has the world’s leading hypersonic missile arsenal and continued to advance the development of conventional and nuclear-armed hypersonic missile technologies during the past year.” It bears emphasis that all ballistic missiles are hypersonic (faster than Mach 5) during a portion of their flight. What is new is the recent fielding of mature, hypersonic missiles with maneuvering payloads by American adversaries, including Russia and China.

China’s fielded hypersonic missiles, including its ASBM families, combine very high speed with maneuverability to greatly complicate missile defense and fleet operations. Maneuvering payloads can approach from unexpected azimuths, fly at lower-than-traditional trajectories, and potentially exploit gaps in radar and interceptor coverage. In exchange for these advantages, such systems may trade some speed in the terminal phase to reduce ionized plasma-related effects that can interfere with guidance and communications, while remaining firmly hypersonic.

Taken together, China’s ASBMs—now potentially extending to intercontinental ranges with the DF-27—pose a potent threat to surface ships across much of the Pacific. In effect, they constitute a new form of naval force. Although the United States and its allies possess manifold countermeasures in what would be a complex systems-of-systems contest, there is no denying that, by becoming the first major ASBM power and steadily expanding its ASBM families, China has dramatically changed the naval balance and the prospective ways of war in the Western Pacific and beyond.

Meanwhile, even as Beijing pursues what U.S. defense assessments such as the Pentagon’s 2025 report show to be the world’s most rapid, expansive buildup of nuclear and conventional ballistic missiles—including the fielding of missile families such as the DF-21, DF-26, and DF-27 with both nuclear-capable and conventional (including ASBM) variants, whose operational employment could increase the risk of warhead ambiguity or misinterpretation in a crisis—China has thus far proven unwilling to engage in sustained, substantive nuclear or conventional ballistic missile risk-reduction or arms-control discussions. As Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping seeks to expand operational options across manifold rungs of the escalation ladder to strengthen coercive leverage and potential warfighting capabilities (particularly regarding a Taiwan contingency), the attendant risks continue to grow. The latest revelations concerning the DF-27 ICBM are an important new chapter, but are far from the end of the story.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author alone, based solely on open sources. They do not necessarily represent the views, policies, or positions of the U.S. Department of War or its components, to include the Department of the Navy or the U.S. Naval War College.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is Professor of Strategy in the U.S. Naval War College (NWC)’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI). A core founding member, he helped establish CMSI in 2004 and stand it up officially in 2006, and has played an integral role in its development; from 2021–23 he served as Research Director. He is a China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Associate, and is currently a Visiting Scholar at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, where he has been an Associate in Research since 2008.

This analysis appears courtesy of Andrew S. Erickson and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.