Beware Buyer's Remorse: Why the Coast Guard Should Avoid the LCS

[By Lt. Joseph O’Connell]

With all the negative publicity surrounding the Navy’s littoral combat ship (LCS) program, it would seem self-evident the Coast Guard has no interest in acquiring the LCS as a hand-me-down. However, with the recent publishing of “In Dire Need: Why the Coast Guard Needs the LCS,” a newly found interest in acquiring problematic navy platforms may be growing and deserves to be judged on its merits. The central thesis proposes the U.S. Coast Guard acquire decommissioned LCSs from the U.S. Navy, remove the installed combined diesel engine and gas turbine (CODAG) plant, and install a direct drive diesel. While the proposal is noticeably light on details of propulsion layout (it is unclear if the new layout would have one diesel per water jet or use a splitting/combining gear arrangement), it relies upon the Coast Guard’s historical precedents of accepting old navy ships and converting CODAG plants into direct diesel drives. The concept merits an analytic look to determine if the primary conclusion, that acquiring recently decommissioned LCS’s in lieu of commissioning new Off-shore Patrol Cutters (OPCs) has the potential to save scarce Coast Guard dollars, holds true. To do so, a rough exploration of what this program would achieve and at what cost must be compared to OPC designs and costs.

The LCS: Built for Speed

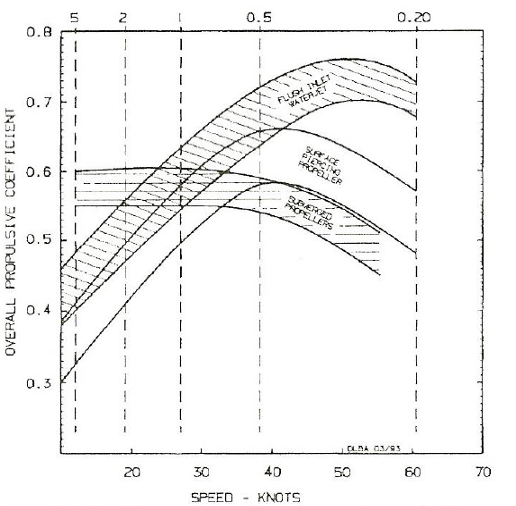

One of the driving requirements for the LCS acquisition was “sprint” speeds in excess of 40 knots. Such speeds effectively ruled out traditional propellers as prime movers with water jet systems taking their place. The Coast Guard does not and has not operated large vessels with water jet drives, and significant propulsion inefficiencies exist when operating these drives at lower speeds (Fig 1). Because of the governing physics behind water jets, they are rarely used in vessels that normally operate under 30 knots. While re-engining itself may be a cost effective way to gut the newly minted cutters of an expensive gear issue, it does not solve the propulsion issue of low speed water jet operation.

Figure 1: Achievable propulsive coefficient for propulsors applicable to high speed monohulls

For argument’s sake, we can assume that the Coast Guard would re-engine the LCS with a comparable engine to the two 7,280 KW fairbanks diesels planned for the OPC, with a total combined brake horsepower (BHP) of 19,520. Using publicly available data points on the LCS speed power curve, and understanding its cubic nature, we see this would deliver an underwhelming 15 to 20 knots at flank speed. And while 15-20 knots may be acceptable for legacy Coast Guard operations, it does not match the OPC’s promised 22-plus knots or the fuel efficiency and lower operating cost of the OPC’s designed loiter drive. Because of the water jet propulsion system, an additional operating cost for the Coast Guard LCS would be fuel and maintenance. Water jets are terribly inefficient at low-medium speeds and would consume 20-50 percent more fuel than the OPC at similar speeds.

Additionally, as evidenced by the national security cutter speed operating profile, the Coast Guard rarely uses high end speeds, with the majority of UW time spent loitering after a bust—mostly position keeping with light load conditions on the plant. This has resulted in numerous main diesel engine (MDE) maintenance issues for the WMSL fleet, and presumably would be the case if the LCS was adopted as well. The OPC was designed with this operational speed profile in mind and has a planned low speed electric loiter drive. This drive will reduce light load conditions that degrade engine life and capability. Additionally, the low speed loiter drive lengthens the cutter’s endurance by limiting fuel consumption, frequently a reason for cutters to return to port for brief stops for fuel (BSFs). Given the slower speed and higher fuel consumption, the LCS would be thoroughly outcompeted by an OPC in the majority of Coast Guard mission sets. Without the loiter drive, the Coast Guard LCS would have high speed diesels powering four water jets, exposing both systems to increased degradation due to low operating speeds.

Shiphandlers Be Warned

Not only would these franken-cutters be fuel inefficient, slower, and expensive to maintain, they would also be significantly more difficult to maneuver. Without the traditional rudder control surface, the LCS utilizes moveable waterjets to achieve both propulsion and steering—a layout with which Coast Guard deck watch officers are unfamiliar. With a new lower speed prime mover supplying power to the waterjet, it is safe to assume that the water volume flow rate would drop, decreasing the effectiveness of the jets for maneuvering. This increases the potential for catastrophic collisions, unplanned maintenance periods, and high repairs costs that familiar and more trusted rudder systems mitigate.

A final, unaddressed concern is the aluminum hull of the Independence variant, originally adopted to lighten the vessel to make sprint speeds more achievable. Aluminum is unsavory for a potential naval combatant due to its low melting point. The USS Belknap fire demonstrates why shipbuilders generally prefer to avoid aluminum. Given the Coast Guard’s growing role in great power competition and the risks associated with blue water naval operations, an aluminum hulled vessel, powered by diesels driving a water jet, sounds about as unappetizing a cutter as could be built.

The True Cost of Re-Engining

The one remaining argument in favor of Coast Guard LCS adoption is its relative cost to the OPC. Current projections indicate an OPC will cost on average $411 million per hull. Taking a big picture analysis, including anticipated operating costs and operational effectiveness, we can make a clear assessment of scrapping the OPCs in favor of recycling the LCS. On the face, it seems that it would be more cost effective to re-engine an existing hull rather than build one from scratch. On average, to re-engine a cutter would require an extensive dry dock period—approximately 12-plus months per hull. This estimate is based upon current re-engining times for the legacy Famous-class cutters that are undergoing an electrical grid upgrade, with new ship service diesel generator (SSDGs) installations taking roughly seven months. Given the bureaucratic processes of transferring control of a ship from the Navy to the Coast Guard, compounded with the engine and gear replacement availability, we can safely assume the first OPC, if not the first few, will have been delivered by the time an LCS would be operational. Given that there is no time delivery advantage for either platform, but significant speed, maneuverability, maintainability, age of hull at delivery and endurance advantages for the OPC the cost savings must be substantial to consider the LCS as meriting adoption.

While it is difficult to accurately forecast the cost of re-engining and gearing a 3,500 ton combatant, we can estimate a range that may be useful for comparison to new construction. Using a standard maintenance dry dock for the WMSL—a similarly sized vessel—as a baseline, we can put a lower threshold of $1 million per month, with roughly a 12 month availability estimated, and the engines themselves costing upwards of $1 million each. Assuming the gear replacement equipment will run similarly expensive, we reach an optimistic $20 million, and a more conservative $40 million per hull. Regardless, either estimate is less than 10 percent of the cost of a new OPC, validating the original assumption that retooling an LCS to take the berth of an OPC would be more affordable. The second major driver of hull machinery and electrical (HM&E) cost is the age of the hull, as vessels age they become relatively more expensive to maintain, given that the first LCS was laid down in 2005, commissioned in 2008, the Coast Guard would be paying upwards of $40 million a hull for a 15-plus year old ship that would be expensive to operate, difficult to maneuver, slower, and less reliable than the planned OPCs.

After a brief overview of the true costs for the Coast Guard to adopt the LCS, it becomes painfully clear that they would be woefully inadequate to replace the planned OPCs. While true that this path would be substantially less expensive in the immediate future, it would be a Faustian bargain, resulting in the Coast Guard operating expensive and ineffective cutters. Such cutters would only serve to weaken the Coast Guard medium endurance fleet. With the shifting geopolitics of today’s world, the U.S. Coast Guard cannot afford to trade well designed affordable cutters for recycled Navy hulls.

The views expressed in this piece are the author's alone and do not represent the positions of any agency or institution.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Lieutenant Joey O’Connell has served aboard two Coast Guard cutters as an engineer. He is currently a Medium Endurance Cutter (MEC) port engineer, planning and overseeing depot-level maintenance on the aging MEC fleet. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and two masters degrees—one in naval architecture and the other in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.