75 Years Ago: The Last Nazi U-Boat Surrenders

Described as a “lanky, hawk-faced man,” Charles Eliot Winslow was born in 1909 and grew up in the Boston area. He preferred using his middle name and, by 1940, he was a successful paint salesman and engaged to be married. Winslow had second thoughts about his fiancé, but instead of calling off the wedding, he chose to join the U.S. Navy. So, in 1941, at the ripe age of 31, he found himself called to active duty with the enlisted rating of seaman 2nd class.

Described as a “lanky, hawk-faced man,” Charles Eliot Winslow was born in 1909 and grew up in the Boston area. He preferred using his middle name and, by 1940, he was a successful paint salesman and engaged to be married. Winslow had second thoughts about his fiancé, but instead of calling off the wedding, he chose to join the U.S. Navy. So, in 1941, at the ripe age of 31, he found himself called to active duty with the enlisted rating of seaman 2nd class.

In his first assignment, Winslow served out of Boston on board USS Puffin, a Maine fishing boat converted into a minesweeper. In November 1941, just before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he decided to apply for an officer’s commission in the United States Coast Guard Reserve. Winslow passed the competitive examination and, by December, he accepted a commission in the Coast Guard.

Winslow rose through the ranks quickly. During 1942, he served as executive officer on board the Coast Guard weather ship Menemsha, and then received an appointment to the anti-submarine warfare school in Miami, Florida. Following graduation, the Coast Guard promoted him to lieutenant junior grade and assigned him to the Argo, a 165-foot Coast Guard cutter originally built for offshore Prohibition enforcement. By February 1943, Winslow served as senior watch officer and navigation officer on board Argo. He rose rapidly through the ship’s officer ranks and, in April, he received a promotion to executive officer and gunnery officer.

After only two months as the cutter’s executive officer, the Coast Guard promoted him to commanding officer of Argo. In June 1944, the senior member of a Navy inspection team reported, “The [Argo’s] commanding officer is an able and competent officer, forceful, decisive, military in conduct and bearing, maintaining discipline with a firm yet tactful hand . . . .” Even though he enlisted to escape his fiancé, Winslow proved a solid leader and an excellent seaman, and the Service would retain him as Argo’s commanding officer for the rest of the war.

Johann Heinrich Fehler followed a different path than his American counterpart. A blond, clean-cut man, Fehler was born a year later than Winslow. As a boy growing up near Berlin, he longed to go to sea. After completing high school, Fehler signed-on with a German sailing vessel plying the waters of the Baltic Sea and, after two years, he began serving on a German ocean-going freighter. He next entered the German merchant marine academy and earned a mate’s certificate. In 1933, he joined Adolph Hitler’s National Socialist Party, which was recruiting new members throughout Germany. In 1936, he joined the German Navy as an officer cadet and he would remain a faithful Nazi Party member for the rest of his military career.

In the later years of the war, Fehler’s fate would be tied to the German submarine U-234. One of Germany’s oversized Type X-B U-boats, this 1,650-ton sub’s original mission was to lay mines rather than torpedo enemy shipping. However, after completing its trials and commissioning as a minelayer, the U-boat returned to the shipyard for conversion into a freight-carrying U-boat to transport vital cargoes through Allied patrolled waters.

Using the schnorkel mast, shown here next to the conning tower, U-boats could run their diesel engines while submerged by sucking air through an intake at the top of the mast while blowing diesel fumes out of the schnorkel’s exhaust manifold. (U.S. Navy Photo)

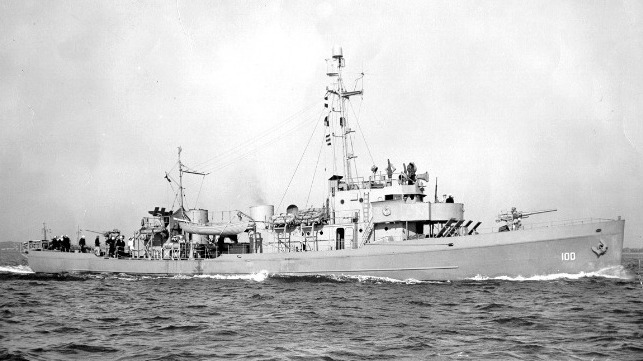

Back in the U.S., the Navy assigned Cutter Argo and its sister cutters to patrol and convoy escort duties. The cutter carried a crew of 75 men and supported radar and sonar equipment; an armament of 3-inch and 20 mm guns; and depth charges and other anti-submarine weapons. As escorts, Argo and its sister cutters were typically assigned to coastal convoys, tracking underwater contacts and attacking anything that resembled the sonar signature of a submarine.

In December 1944, the German high command summoned Johann Fehler to Berlin for meetings. There, he learned that his U-boat would serve as an undersea freighter to ship important cargo to Japan. The Nazi’s had sent U-boats to Japan before, but three out of four submarine freighters had been lost attempting the passage. However, toward the end of the war there was no alternative for shipping cargoes to Germany’s last surviving ally. Fehler’s assignment to command a transport U-boat proved deeply disappointing, because he wanted to join the fight and command one of the attack subs. But Fehler stayed with U-234 since requesting another position meant postponing his deployment or, even worse, serving in a shore assignment.

Shipping space was limited in even the largest U-boats. To maximize U-234’s capacity, the Germans allocated every conceivable watertight compartment to critical war material. The 300 tons of cargo included many of Germany’s latest armaments and military technology, such as new radar; anti-tank and armor weapons; and the latest explosives and ammunition. Military aviation materials included documents, technical drawings and instrumentation for Messerschmitt’s latest fighter aircraft. U-234 also carried raw materials rarely found in Japan, such as lead (74 tons), mercury (26 tons), optical glass (7 tons) and uranium oxide ore (1,200 pounds). By 1945, lines of communication between Germany and Japan had become tenuous, so U-234 also carried one ton of mail and correspondence for German military, diplomatic and civilian personnel located in Japan.

This image shows Argo moored at Portsmouth Navy Yard on May 19th, 1945, with U-234 crewmembers assembled on the fantail and Coast Guard officers and men looking on. (U.S. Navy Photo)

Not only did Fehler have to transport vital cargo to Japan, his orders required him to ferry critical military personnel. His twelve passengers included two officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy, two civilian employees of the Messerschmitt Aircraft Company, and four German naval officers. U-234 also carried four German air force officers, including flamboyant Luftwaffe general Ulrich Kessler.

Fully loaded with top-secret cargo and passengers, U-234 departed Kiel, Germany, on March 25th on course for Kristiansand, Norway. On April 15th, Fehler deployed from Norway dubious of his mission’s chances of success. He cruised without surfacing for more than two weeks using the U-boat’s advanced schnorkel system and, by early May, he reached the open ocean. In the meantime, the Nazi war machine had collapsed, Adolph Hitler had killed himself and other Nazi leaders had fled Berlin. So the surrender of German military forces fell to Admiral Karl Dönitz, former head of the German submarine fleet.

On May 8th, 1945, Dönitz broadcast the order for all deployed U-boats to surrender to Allied naval forces. By the time he received the order, Fehler was halfway across the Atlantic. He decided to surrender to the Americans and began steaming westward. Meantime, his two Japanese passengers chose to commit suicide to avoid capture and Fehler buried their bodies at sea.

On Saturday, May 19th, Argo rendezvoused with U-234 and its Navy escort, USS Sutton. Sutton’s whaleboat ferried Fehler, his officers and his passengers over to the cutter. According to Commander Alexander Moffat, the senior Navy representative on board Argo, Fehler climbed over the cutter’s rail and cheerfully extended his hand in greeting, but Moffat did not return the German’s proffer of a handshake. Denied a warm greeting by the American, Fehler proceeded belowdecks with his men, remarking, "Come now, commander, let’s not do this the hard way. Who knows but that one of these days you’ll be surrendering to me? In a few years, you will see Germany reborn. In the meantime, I shall have a welcome rest at one of your prisoner of war camps with better food, I am sure, than I have had for months. Then I’ll be repatriated ready to work for a new economic empire."

In his personal collection of photos from surrender of U-234, LTJG Eliot Winslow’s hand-written captions included: “The Finger: May 19, 1945, Kapitanen Leutnaut [sic] Jahann Heinrich Fehler . . . said in good English, ‘Ach—my men have been treated like gangsters.’ With eyes meeting head on, I barked ‘that’s what you are GET OFF!’ My outstretched arm pointed to the gangway.” (Courtesy of the Winslow Family)

Below, Argo’s armed guard ordered the prisoners to sit still with their arms folded prompting Fehler to complain bitterly to the American interpreter about their treatment. After learning about Fehler’s behavior, Winslow went below and ordered the guards to “shoot any prisoner who as much as scratches his head without permission.”

After they moored at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, an armed guard escorted U-234’s personnel to the brig. Luftwaffe General Kessler saluted Winslow and politely asked permission to depart the ship, to which Winslow silently pointed the way. Fehler left the cutter protesting to Winslow “Your men treated me like a gangster.” Already simmering over Fehler’s hubris and loud behavior, Winslow pointed to the gangway and barked, “That’s what you are. Get the hell off my ship!”

Navy officials deemed Fehler, his passengers and officers of significant intelligence value and flew them from Boston to Washington, D.C., for further interrogation and processing.

Meanwhile, the Navy disbanded Winslow’s surrender group. Later, Winslow expressed his interest in returning to civilian life. In a letter to his command, he wrote, “If the Argo . . . is scheduled to fight the wintry blasts alone all winter, my answer is ‘Get me off.’ One winter upside down was enough for me. It took me three weeks [on shore] to regain the full use of my feet!”

To determine the contents of U-234’s cargo, the Navy surrounded the submarine with a shroud to shield the sensitive unloading activities. The Navy Department sent much of U-234’s cargo to its research facility at Indian Head, Maryland, distributing the German technology, including the Messerschmitt plans and instruments, to appropriate government offices for research and analysis. The Navy handed over the uranium oxide to the U.S. Army to support the Manhattan Project and development of atomic weapons.

Ultimately, U-234 was used for target practice by the U.S. Navy. On November 20th, 1947, USS Greenfish shot a torpedo at her as she lay on the surface, approximately 40 miles off Cape Cod. (U.S. Navy Photo)

After U-234’s surrender, the Navy continued to analyze the U-boat’s design and construction. The Navy subjected the U-boat to numerous tests to compare the durability and performance of German submarines to the latest American sub technology. By the spring of 1946, extensive dockside inspections and sea tests were complete and the Navy formally declared the U-boat “out of service.” Finally, on November 20th, 1947, 40 miles off Cape Cod, the Navy used the U-boat as a torpedo target for the American submarine USS Greenfish.

Navy intelligence officials processed Fehler and the other U-234 officers through Fort Hunt, located near Mt. Vernon. After that, the Navy sent the officers to internment camps along the East Coast. Fehler went to a facility reserved for fervent Nazi officers and, in 1946, he returned home by sea along with other repatriated Germans. While Fehler sank no ships as a submarine commander, his association with U-234 made him the subject of journalists, writers and researchers as one of the better-known U-boat captains. After returning to Germany, he settled in Hamburg and passed away in 1993 at the age of 82.

After completing the successful transfer of surrendered U-boats to Portsmouth, Captain Winslow navigated Argo up to Southport, Maine, to anchor in front of his parents’ home on Love Cove. The cutter barely fit through the rocky narrows and is the only vessel of its size and kind to have visited the sparsely populated area. (Courtesy of the Winslow Family)

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

After retiring from active duty, Eliot Winslow settled in Southport, Maine (near the port city of Bath), where he started a business running tugs and local tour boats. For years, Winslow gave summertime tours of the southern Maine coast on board the sightseeing vessel he named for his old cutter, the Argo. Winslow lived to see his nineties at his home in Southport.

William Thiesen is the Coast Guard Atlantic Area historian. This article appears courtesy of Coast Guard Compass and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.