U.S. National Security Leaders Leaked Houthi War Plans to a Journalist

Senior members of the Trump administration, including the secretary of defense, accidentally texted the Pentagon's future war plans for bombing strikes in Yemen to a journalist whom they had invited into a group chat. The White House has confirmed that the conversation was authentic, acknowledging that some of the most well-known names in the Trump administration leaked the positions and planned operations of U.S. Navy and Air Force servicemembers in Yemen to a reporter. In addition to the security implications of the leak itself, the use of an unauthorized commercial app for the highest levels of secret defense talks raises questions about operational security and the preservation of federal records: the app, Signal, is typically used on low-security commercial phones, and it was set to delete messages automatically after a predetermined period of time, thereby erasing any record of the conversation (if the reporter hadn't saved it).

The journalist who was inadvertently invited to the group chat - The Atlantic's managing editor, Jeffrey Goldberg - had the integrity not to publish the details of the war plans, since doing so could compromise the safety of American soldiers. He did, however, release screenshots and text of the group's deliberations the day before the strikes, including apparent skepticism by Vice President JD Vance about whether the U.S. should be involved in Yemen at all.

It started on March 13, when Goldberg received a Signal invite from Michael Waltz, Trump's national security advisor. He was invited to join a meeting called "Houthi PC small group," inviting a list of extremely important personnel to join a "principles group" [sic] meeting about "coordination on Houthis" to follow up on discussions in the "Sit Room." (A principals group is a gathering of executive branch leaders at the cabinet level.)

In the group chat, Signal users with the usernames MAR, JD Vance, TG, Scott B, Pete Hegseth and John Ratcliffe responded to the chat invite and nominated representatives to attend, all of whom were well-known aides to top officials. The White House has confirmed the authenticity of the texts, and from either context or verbatim language, the Signal usernames appear to correspond to Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Vice President JD Vance, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and CIA Director John Ratcliffe (respectively). Other users present on the invite list were Susie Wiles, likely the White House Chief of Staff, and S M, likely senior Trump advisor Stephen Miller.

Jeffrey Goldberg's username was included in the group chat list as "JG," bearing some accidental resemblance to "JD," and no one questioned his presence. At this early stage, Goldberg suspected that the chat was fake, either a disinformation campaign or someone attempting to embarrass a media organization. "I had very strong doubts that this text group was real, because I could not believe that the national-security leadership of the United States would communicate on Signal about imminent war plans," he later wrote.

The meeting began at 0805 on March 14, all by Signal. The account "JD Vance" wrote in to say that he was busy that day in Michigan (he was) and added that he thought "we are making a mistake" by intervening in Yemen, since Europe is the primary beneficiary of Suez Canal trade. He suggested that the American public might not see the point of opening up the Red Sea to European navigation, except for the purpose of sending a message to foreign adversaries. "I am not sure the president is aware how inconsistent this [Red Sea campaign] is with his message on Europe right now," the "JD Vance" account wrote. "I just hate bailing Europeans out again."

The person with the "Pete Hegseth" account concurred with "loathing for European free-loading," but voted for going ahead with strikes on the Houthis in order to reestablish deterrence, even if "nobody knows who the Houthis are" in America and the strikes might require certain political messaging to explain. The "Michael Waltz" account suggested that the costs of the strikes could be billed to Europe after the fact.

"S M" concluded the conversation by saying that "the president was clear: green light," though he emphasized that "there needs to be some further economic gain extracted [from Europe and Egypt] in return."

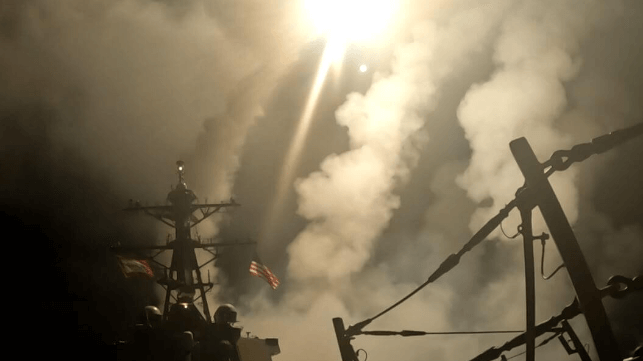

At 1144 hours on March 15, Goldberg received a "team update" from the account labeled "Pete Hegseth." It contained the secret operational details for imminent airstrikes on Yemen, including "targets, weapons the U.S. would be deploying, and attack sequencing," with the first strikes scheduled to hit at 1345 hours. Since the details could be used to harm American personnel if they were indeed authentic, Goldberg did not publish them. However, he was quickly convinced that they were real: at 1355, right on time for the "team update" schedule, the first strikes were reported in Sanaa, Yemen.

Goldberg then followed up with Waltz, Gabbard, Ratcliffe and Hegseth by email and Signal, asking if the thread was genuine. A spokesman for the National Security Council responded later that day, confirming that "this appears to be an authentic message chain, and we are reviewing how an inadvertent number was added to the chain."

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

U.S. intelligence agencies and cybersecurity experts have warned for years that Signal can be hacked or bypassed, including with commercially-available spyware. The app is a known target for Russia's GRU intelligence agency.

A former defense official told CNN that in order to copy the detailed Yemen war plans from a classified platform into the Signal chat, the details would have had to be re-entered manually. A simple "copy and paste" is not possible with the Pentagon's secure communications systems. "You would either have to print it out or type it up while looking at both screens. So he had to have done it or somebody would’ve had to have done it for him that way," the official said.