Researchers Find Wreck of 100-Year-Old Laker off Michigan

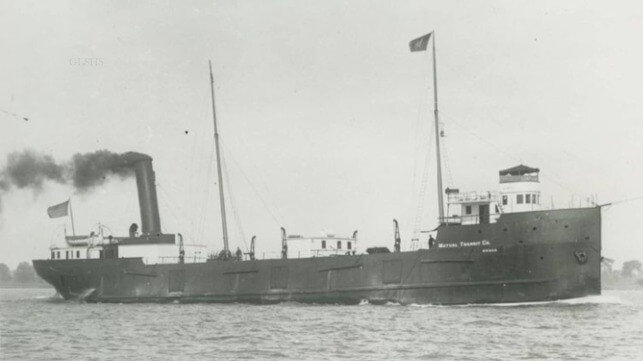

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society has discovered the wreck of the freighter Huronton, which went down after a collision on Lake Superior almost exactly 100 years ago.

On October 11, 1923, the 240-foot steel-hulled freighter Huronton was upbound on Lake Superior. Visibility was poor due to a combination of fog and forest fire smoke. A larger freighter, the 400-foot Cetus, was approaching on a downbound course. Cetus struck Huronton's port side amidships, penetrating the smaller vessel's hull. The master of Cetus knew well enough to keep his engines engaged ahead, keeping the freighter's bow in the hole and slowing down flooding. The crew of the Huronton had enough time to safely abandon ship - with one exception, the crew's bulldog, which was tied up towards the stern.

According to accounts of the incident, the chief mate, Dick Simpell, jumped back over to the Huronton and rescued the dog before the vessel slipped below. The freighter had stayed afloat just 18 minutes after the collision.

100 years later, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society and its research boat, the R/V David Boyd, spotted the wreck of the Huronton in a sonar survey. The Boyd's towed sonar spotted a faint signal in a small depression on the bottom at a depth of 800 feet. The crew came back to look later and made a careful pass, and they came back with a clear sonar depiction of a wrecked freighter, sitting upright and intact with its hatches clearly visible.

A later survey with an ROV revealed the ship's condition in great detail, including the hole that sent it down.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

"Finding any shipwreck is exciting. But to think that we’re the first human eyes to look at this vessel 100 years after it sank, not many people have the opportunity to do that," said GLSHS Executive Director Bruce Lynn.

The society's mission to find and document Great Lakes wrecks has become more important than ever. Invasive quagga mussels are gradually colonizing and degrading shipwrecks in every one of the Great Lakes except for Lake Superior, where they are still limited to the most high-traffic harbors. However, if the mussels continue their spread, Lake Superior's perfectly-preserved wreck sites could be in danger of eventual colonization as well.