Newly-Discovered Prehistoric Whale May Have Been Heaviest Animal Ever

A newly-discovered species of prehistoric whale may have been the heaviest animal in history, according to a team of Italian researchers.

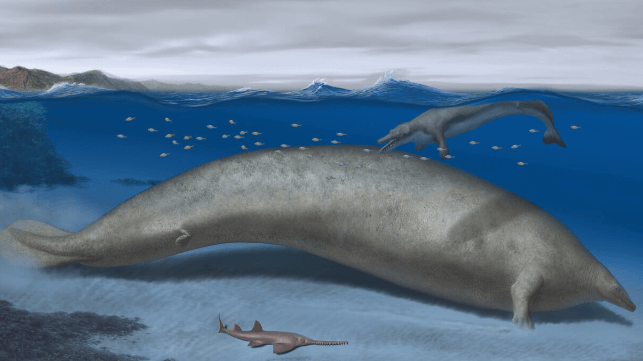

13 years ago, a group of paleontologists from the University of Pisa uncovered a set of unusually large, high-density whale bones in a fossil bed in the remote Ica desert of Peru. By the age of the rock, the fossils date back about 40 million years. The bones came from a cetacean, but not like those found in today's oceans. This creature was stout in proportions, five meters shorter than a blue whale and three times heavier, and it may have had small legs for browsing along the seabed.

The massive creature - named Perucetus collosus for the location of its discovery - had a skeleton that weighed about 5-8 tonnes, according to lead researcher Giovanni Bianucci. This is at least twice as heavy as the skeleton of a blue whale, and three times as heavy as the skeletal structure of the largest dinosaurs. For perspective, the lightest single vertebrae that the team found weighed more than 200 pounds.

Giovanni Bianucci / University of Pisa

The creature's very large, heavy bones would support an unusually large mass, and it was likely the heaviest mammal on record - and quite possily the heaviest animal of any kind. Conservatively, the team estimated the lower bound of its weight at about 85 tonnes, but some specimens may have weighed in at up to 340 tonnes.

"The enormous body mass of Perucetus indicates that cetaceans developed phenomena of gigantism at least twice: in relatively recent times, with the evolution of the large baleen whales that inhabit the modern oceans, and some 40 million years ago," said Bianucci.

The discovery was made more than a decade ago, but the researchers proceeded carefully in evaluating the find, and their results were finally published this week in Nature. The sheer mass of the specimens made the process of study difficult, and the team turned to 3D scanning and virtual models to make handling easier.

"All the bones of Perucetus are made up of extremely dense and compact bone, similar to that found, though in a much less marked way, in the present-day sirenians [manatees, dugongs and sea cows]. The latter live in shallow coastal waters, where a particularly heavy skeleton acts as a 'ballast', thus facilitating feeding at the seabed and increasing the inertia to the action of waves," said co-author Alberto Collareta.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

This kind of skeletal thickening is not found in any living cetacean, Collareta said - but he believes that it is likely that it served the same function, allowing Perucetus to navigate and feed on the bottom near the coastline. "Perucetus probably fed near the seabed, perhaps searching for the carcasses of other marine vertebrates as some large-bodied sharks do today," he said.

The sedimentary rock where the fossilized skeleton was found contains additional clues that point to coastal habitat. At the time of the specimen's demise, southern Peru's stark coastal desert was a vast bay, the Pisco Basin. According to geologist Claudio di Celma, this region had high biodiversity and plenty of nutrients. It may hold further secrets under the sands. "I would be the surprises aren't over yet," said Bianucci in a statement.