German World War II Cruiser Discovered Off Norway

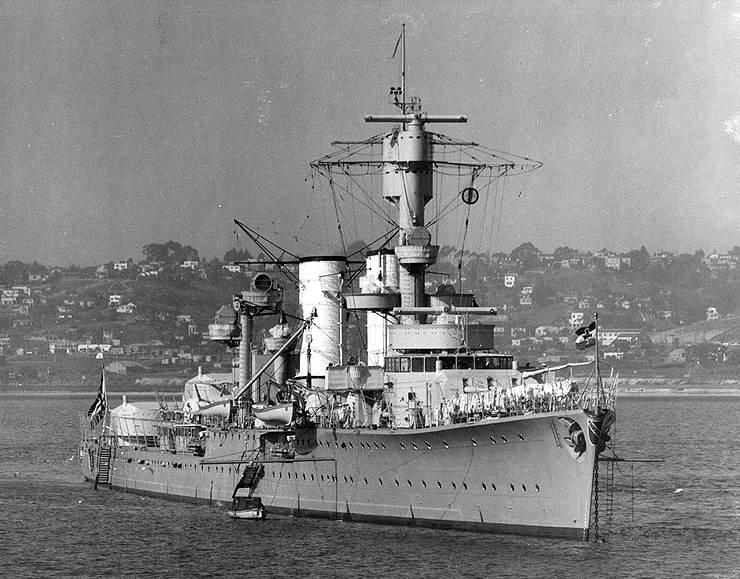

Karlsruhe 1934 in San Diego - U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph

The wreckage of one of Germany’s most famous World War II-era vessels, the light cruiser Karlsruhe, was recently found quite by accident in the waters off Norway. While the history of the vessel, which was the only large German ship lost during the Nazi invasion of Norway in 1940 was well known, until now the wreckage of the ship had never been located.

According to reports from Norwegian energy company Statnett, during a routine inspection in April 2017 of a power cable running from Norway to Denmark along the seafloor, they noticed the image of a shipwreck. It was approximately 15 meters from the undersea cable and from the images on sonar it appeared to be a large vessel.

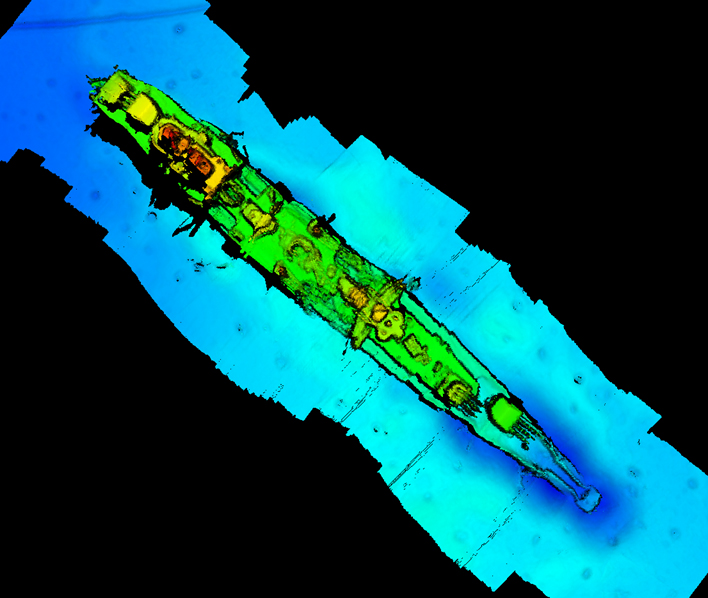

Image from the ROV of the vessel on the seafloor - all current images courtesy of Statnett

Three years later, in June 2020, an expedition got underway aboard the offshore vessel Olympic Taurus to explore the wreck which was lying approximately 13 nautical miles from Kristiansand in southern Norway. Statnett’s senior project engineer Ole Petter Hobberstad working with a team of experts got their first glimpses of the vessel using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) with multi-beam echo sounders.

“When the ROV results showed us a ship that was torpedoed, we realized it was from the war,” Hobberstad says. “As the cannons became visible on the screen, we understood it was a huge warship. We were very excited and surprised that the wreck was so big.”

Analysis of the images confirmed that they had located the final resting place of the German light cruiser Karlsruhe approximately 490 meters below the surface resting upright on the seafloor. “You can find Karlsruhe's fate in history books, but no one has known exactly where the ship sunk,” explains Frode Kvalø, archaeologist and researcher at the Norwegian Maritime Museum. “After all these years we finally know where the graveyard to this important warship is.”

Construction of the Karlsruhe had begun in 1926 with the hull being launched the following year. With Germany’s navy severely restricted by the World War I armistice, the vessel along with two sister ships was among the largest and finest ships of the German navy during that era. She was commissioned in 1929. Measuring 571 feet in length and powered by steam turbines she could achieve speeds of 32 knots. She was manned by 21 officers and 493 sailors. Her primary armaments were nine 150mm/60 guns C/25 in three turrets. The ships had an unusual placement of two aft turrets each offset to one side of the hull.

During the 1930s the Karlsruhe was used primarily as a training vessel for the German navy making a range of cruises including around the world voyages. She was also deployed off Spain during the revolution. In 1938, the ship was sent to a shipyard for a major reconditioning which prepared her for World War II.

The Karlsruhe saw action in the Baltic and she ordered to carry troops for the invasion of Norway. Sailing from Bremerhaven on April 8, 1940 heading to Kristiansand, she lay off the city waiting for a heavy fog to lift. As she entered the fjord the following day she came under heavy bombardment with the cruiser and the Norwegian guns engaged in the artillery barrage for nearly two hours before the fog again covered the port. The Norwegian surrenders and the Karlsruhe disembarked the troops.

The Karlsruhe was outbound from the fjord when she was attacked by a British submarine. She was hit by two torpedoes, one forward and one midship. Flooding it was determined that the cruiser was mortally wounded and could not make the voyage back to Germany. Her crew abandoned the ship and a German torpedo boat fired two more shots sending the Karlsruhe to the bottom.

Barrels from the ship's famous guns on three turrets - all current images courtesy of Statnett

The images of the vessel on the seafloor are unique according to Kvalø in that the Karlsruhe is sitting upright with her turrets intact. He says that most warships, with a high center of gravity, typically roll over when they were sunk.

Statnett’s Hobberstad says that he is glad that they finally got the opportunity to investigate the mysterious wreck so close to their cable and could share the news of their discovery with the world.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

All current images courtesy of Statnett