CBO Predicts Higher Costs Ahead for U.S. Navy's Shipbuilding Plans

The U.S. Navy has released five different shipbuilding and force structure plans since 2016, and the Congressional Budget Office - Congress' non-partisan scorekeeper - has made a valiant effort at keeping up with of them. When considering that the latest version has three different options, it's an even bigger job. CBO has delved into the details of what each will cost over the span of the coming decades, and it projects that the price will be steep in all cases: $30-33 billion per year for the next 30 years, a sharp increase over the current average of $24 billion.

The CBO believes that future shipbuilding costs will be 14-18 percent higher than the Navy predicts, and this may not be unusual, as overruns are almost always encountered. The divergence is centered on the 2043-52 time period and is largely due to estimates for two specific programs: the service's next-generation attack sub and destroyer.

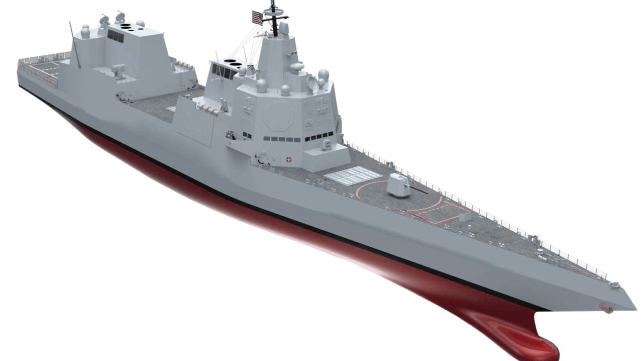

The CBO thinks that the Navy's next-generation destroyer program will cost about $1 billion more per hull than the service estimates, in large part because it is physically larger. DDG(X) is supposed to repurpose many of the combat systems of the 9,500 tonne Arleigh Burke-class platform, but in a new hull that displaces 13,500 tonnes. The Navy projects only a 10 percent cost increase for the switch to the DDG(X) - but, citing past programs like the Zumwalt-class, CBO projects that a ship that is 40 percent bigger will cost about 40 percent more.

Likewise, CBO predicts that each SSN(X) next-generation attack submarine will cost about $1.0-1.5 billion more than estimated, though the task is more challenging because the details of the program are still in development. The sub's features and size are as-yet-undecided, but it is expected to outperform the Virginia-class in speed, stealth and armament. Its characteristics look comparable to the high-end Seawolf-class, for which cost of construction is known, but bigger. Using an enlarged Seawolf as a baseline for comparison, CBO predicts that each one will cost $6.2-7.2 billion, up from the Navy's more optimistic $5.6 billion.

Depending on how many dozens of hulls the Navy orders (and the numbers vary markedly between each of the three shipbuilding options), the price estimates add up to a difference measured in the tens of billions of dollars over the span of several decades.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

CBO's sticker-shock price hikes also stem from the Navy's decision not to factor in shipbuilding inflation. On average, U.S. naval shipbuilding inflation outpaces ordinary inflation by about one percentage point every year, according to the CBO. If that rate continues, it means that even before factoring in everyday gas-station-variety inflation, a $2.5 billion ship built today would take $3.3 billion to build in 2045.

And as budget analysts well know, the price of a ship is a small part of the lifecycle cost. Any of the three force structure plans would require the Navy to grow its overall budget by a third in order to man and care for a larger fleet. This would amount to an additional $70 billion a year (in current dollars) by 2052, according to CBO. The sustained cost increase implies real-world tradeoffs: $70 billion is equivalent to the entire federal highway budget, or 10 years of Corps of Engineers waterway improvement funding.