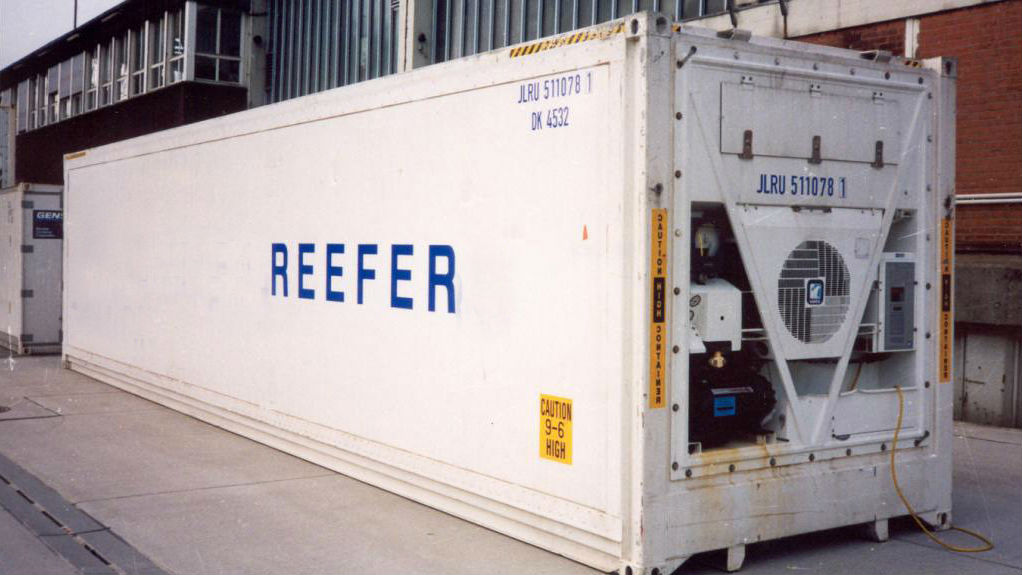

Black Market Refrigerants Pose Shipping Risk

In 2011, several refrigerated, reefer containers exploded, killing three port workers. While there have been no further tragedies since then, counterfeit refrigerants remain in circulation and still represent a significant safety risk.

Counterfeit refrigerant cylinders typically consist of a dangerously unstable cocktail of gases, blended to roughly mimic the most common refrigerant, R-134a. These cylinders are often loaded with rogue gases such as R-40. Though similar to R-134a, R-40 reacts with aluminum to form trimethylaluminum, a highly volatile substance that, when exposed to air, can explode. At best, these fake refrigerants perform poorly, are energy-inefficient and are likely to damage hoses, seals and compressors. At worse, they are highly toxic, and in the case of the fatal accidents in Vietnam, China and Brazil in 2011, highly volatile.

According to international insurer TT Club, R-40 contamination accounts for 0.2 percent of the world’s reefer container fleet, affecting about 2,500 reefers. However, other counterfeit refrigerant mixtures, such as those containing R-50, R-744, R-22 or R-170, are also considered unsafe, so the number of reefers affected could be far higher.

Disposables a permanent problem

Some operators may be unaware of the potential risk of using counterfeit refrigerants, while others may be seeking to cut costs. However, the main reason these refrigerants continue to circulate is because of the continued existence of disposable cylinders. According to Svenn Jacobsen, Technical Product Manager, Refrigeration, Wilhelmsen Ships Service, the absence of a worldwide ban has created a robust market for counterfeiters. “These cylinders are the container of choice for the counterfeiter,” he says. “Cheap and untraceable, no counterfeiter is ever going to get any complaints from their customers using this type of packaging.”

Jacobsen explains that counterfeiters offer what appear to be authentic, trademarked refrigerants. Despite the efforts of leading manufacturers such as Honeywell, Linde and Dupont, which have taken legal action to crack down on counterfeiters and changed packaging to discourage fakes, counterfeit refrigerants remain an industry menace. Even elaborate precautions, such as holographic seals or cylinder stamps, are easily copied in days rather than months. For Jacobsen, the only way to put an end to this illegal and dangerous market is to ban disposable cylinders.

“If the legitimate refrigerant suppliers no longer provided refrigerants in disposable cylinders, the counterfeiters would be out of business,” he says, noting that WSS does not offer refrigerants in disposable cylinders. “We don’t support their use and we believe a worldwide ban is far overdue.”

Whether or not a global ban on disposable cylinders will come into force anytime soon is unclear. In 2007, the E.U. banned disposable refrigerant cylinders in the E.U. and on E.U. flagged vessels. Similar bans are also in place in Canada, India and Australia. However, disposable refrigerant cylinders are still in use elsewhere in the world.

Unintended consequences

More recently new E.U. legislation, introduced in January of this year, may only exacerbate the issue. The new E.U. regulation applies to the use of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) R-134a. HFCs are fluorinated greenhouse gases (f-gases) with a relatively high Global Warming Potential (GWP). So while R134-a is an ozone-friendly, chlorine-free, energy-efficient, low toxicity refrigerant, its use accelerates climate change. The E.U. regulation (EC517/2014) calls for the total supply of HFCs across the E.U. to be reduced to just 63 percent of the 2009-2012 baseline quantity by 2018, measured as the total tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). This sustained reduction in capacity will continue until it reaches just 21 percent of the original baseline figure by 2030.

While Jacobsen applauds the E.U.’s bold move to reduce the environmental impact of R-134a refrigerants, he cautions that these regulations may inadvertently create a strong market for suppliers of counterfeit refrigerants. “It is likely that the reduction in the supply of E.U. HFCs will lead to shortages and a sharp spike in costs, meaning some operators will be tempted to purchase lower-price refrigerants,” he says. “This regulatory change will create an ideal market for counterfeiters. Despite numerous warnings, accidents and fatalities, many operators will be more willing to take a chance on gases packaged in disposable cylinders by unregistered suppliers. We anticipate that the counterfeiters of R-134a are going to be very busy in the years ahead.”

In the absence of a global ban, it is up to operators to use common sense, coupled with a healthy dose of skepticism. Because fake refrigerants are found exclusively in disposable cylinders, Jacobsen recommends that operators only purchase refrigerants supplied in refillable, re-usable, traceable cylinders. For operators who insist on using disposable units, they should make sure a reputable company, which has been audited and approved by a licensed manufacturer, is supplying their refrigerants.

Jon Black, Global Head of Chemicals and Refrigerants, Linde Gases, suggests that operators only source refrigerants from well-known providers or companies who distribute the products for these main manufacturers. “If a new distributor appears on the market, we recommend operators conduct a thorough audit before making a purchase,” he says.

Finally, if the price quoted for gases is way below the market average, it is likely to be a counterfeit.