Australian Navy Captain from Melbourne - Evans Collision Dies

The Royal Australian Navy has honored the life the man in change of HMAS Melbourne (II) when the U.S. Navy Destroyer USS Frank E Evans turned under the Australian aircraft carrier's bow and was cut in half.

Captain John Philip Stevenson died on January 30, aged 98, after a career marked with distinguished service in war and peace, as well as tragedy and controversy.

In 1969 he was in command of HMAS Melbourne (II) when the tragedy occurred in which 75 U.S. Sailors died. He was subsequently cleared by Court Martial for any responsibility and in 2012 received an official apology from then Defence Minister Stephen Smith for having been tried. The apology letter acknowledged the unnecessary stress the Court Martial caused to Stevenson and his family.

Stevenson received a ceremonial funeral in the Garden Island Naval Chapel in Sydney, something normally reserved for officers who pass away during their service at the rank of Captain. This is the first time in the Royal Australian Navy’s history that a serving Captain’s funeral has been held for a retired officer.

Chief of Navy, Vice Admiral Mike Noonan, said the ceremonial funeral recognized the very great contribution made by Stevenson in peace and war to the Navy and the nation. “Captain JP Stevenson has been accorded a ceremonial funeral of a serving Navy Captain to recognize that the circumstances in which he resigned from the Navy were unique and to ensure there can be no doubt as to the very great esteem in which he is now held across our Navy,” Noonan said.

“There can be no doubt that past mistakes were made that impacted both Captain Stevenson and his family. The Navy of 2019 is a more people focused organization and strives to ensure that similar mistakes are not repeated.

“With the passing of Captain Stevenson, our Navy family has lost a fine leader and consummate gentleman, who served Australia with pride in war and peace over a 35 year career and continued to support our Navy long after his time in uniform. We hope today’s formal farewell, in addition to the formal apology Captain Stevenson received from Government in 2012, will help ease the burden which the Stevenson family has had to bear over the past five decades,” Vice Admiral Noonan said.

As part of the ceremony, Stevenson’s coffin was carried into the Garden Island Naval Chapel by six serving junior sailors from HMAS Melbourne (III). As the hearse passed through Fleet Base East, Melbourne’s ship’s company lined the rails of the warship as a mark of respect, while wharf sentries from other ships saluted. Stevenson was also given a seven gun salute, which is normally reserved for serving officers who die while in command of a ship or shore establishment.

A Remarkable Career

Stevenson entered the Royal Australian Naval College (which was then at HMAS Cerberus) as a 13-year-old Cadet Midshipman in 1934.

Stevenson entered the Royal Australian Naval College (which was then at HMAS Cerberus) as a 13-year-old Cadet Midshipman in 1934.

As a junior officer, he saw war service in HMA Ships Canberra, Nestor, Napier and Shropshire.

He was present in Yokohama Bay for the Japanese surrender in 1945 and witnessed the results of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. He was engaged in getting many sick and malnourished prisoners of war embarked for their return to Australia.

After the war, Lieutenant Stevenson went to the United Kingdom on loan to the Royal Navy where he saw operational service in the early days of the Malayan Emergency.

Promoted to Lieutenant Commander in 1950 he returned to Australia in the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney (III).

Upon arrival in Australia he took command, in March 1951, of the frigate HMAS Barcoo which operated as the Royal Australian Navy’s training ship.

He later served in the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia (II) as navigation officer, and later re-joined Sydney as the Fleet Navigation Officer.

Sydney visited the United Kingdom for the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II where Stevenson commanded the Royal Australian Navy detachment during the coronation parade.

In 1954, Commander Stevenson was Director of Plans in Navy Office and also served in HMY Britannia as the naval equerry to His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh during the Royal visit to the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne.

He commanded the destroyer HMAS Anzac (II) from January 1957 to June 1958 and in May 1959 was appointed as the Defence attaché to Thailand, where he was promoted to Captain in December 1960.

Captain Stevenson assumed command of HMAS Watson, in October 1961, and the following October took command of the destroyer HMAS Vendetta (II) as well as commanding the 10th Destroyer Squadron.

In April 1964, he commanded the fast troop transport HMAS Sydney (III) which took Australian troops to Borneo. In 1965 he commanded HMAS Cerberus. Then in late 1966 he became the Australian naval attaché in Washington, DC. After returning to Australia he assumed command of the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne (II) in October 1968.

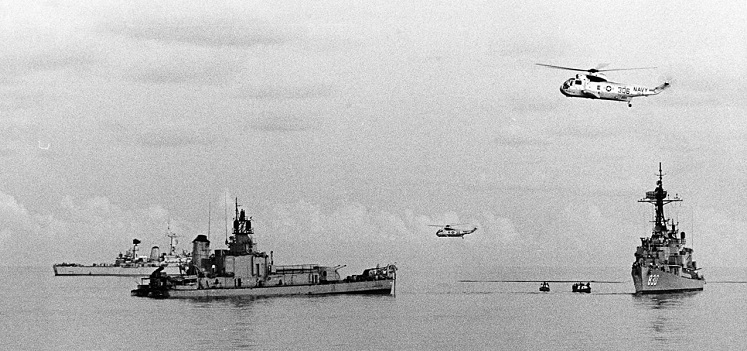

In the early hours of June 3, 1969 in the South China Sea, the American destroyer USS Frank E Evans crossed Melbourne’s bow and was cut in two. The forward section of Evans sank immediately, resulting in the loss of 74 lives, and Melbourne sustained extensive damage to her bow.

A joint U.S. Navy/Royal Australian Navy Board of Inquiry in Subic Bay held Stevenson partly responsible, stating that as Commanding Officer of Melbourne he could have done more to prevent the collision from occurring. However, a subsequent Royal Australian Navy Court Martial cleared him of any responsibility and commended him for his efforts to prevent the collision.

The integrity of the initial Board of Inquiry has since been questioned, particularly as it was presided over by the U.S. Navy Admiral in overall tactical command of Evans at the time of the collision.

Stevenson’s defense counsel at his Navy Court Martial, Gordon Samuels, QC, stated he had “never seen a prosecution case so bereft of any possible proof of guilt.”

Despite being cleared, Stevenson subsequently resigned from the Royal Australian Navy - bringing his distinguished 35-year naval career to an end.

In December 2012, Stevenson received an official apology from the Minister for Defence, Stephen Smith, in which the Minister stated that Stevenson was not treated fairly by the government of the day and the Royal Australian Navy following the events of 1969. Smith described Stevenson as “a distinguished naval officer who served his country with honor in peace and war.”

Following a successful civilian career, Stevenson continued to work with service charities and was appointed as a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in the 2018 Australia Day Honours List.

The Melbourne - Evans Collision

The collision between HMAS Melbourne and the USS Frank E Evans occurred at about 0300 on June 3, 1969 in the South China Sea about 650 miles south-west of Manila, when the Evans ran under Melbourne's bow in the course of changing station from ahead to astern of Melbourne.

Evans was cut in two. The forward part sank shortly afterwards while the after part of the ship swung around and was secured to Melbourne's starboard side aft. U.S. Navy personnel from the after section of Evans were taken on board Melbourne, either onto the flight deck or onto the quarterdeck. Then, after a search confirmed that no one remained in this section of Evans, it was let go.

Melbourne was badly holed forward of the collision bulkhead, and the trim tanks were flooded. Immediate action was taken to shore up, and at that time it was predicted that it would be ready to proceed at slow speed in approximately six hours. Melbourne suffered no personnel casualties.

74 U.S. sailors out of 272 were lost, all inside the bow section of the ship when it sank. Of these, only one body was recovered, that of Seaman Kenneth Wayne Glines, 19, a sailor from the bow section of the Evans. He was picked up by one of Melbourne's boats.

Evans was one of five escorts traveling with the Melbourne during a SEATO exercise, Exercise Sea Spirit, employing 40 ships from six nations. In the morning of the third of June, the Evans was ordered to act as planeguard for the Melbourne. Evans' function as planeguard was to recover any aircraft that happened to ditch into the sea.

On execution of the flying course signal, Evans was to take up position as planeguard, 1,000 yards astern of Melbourne. Evans had experience acting as a planeguard for Melbourne, and had done this on four other occasions.

Stevenson told Evans that the flying course was 260 degrees. The Evans was 3,500 yards in front of Melbourne on the port side, steaming a parallel course to Melbourne's. Melbourne had all navigation lights on at full brilliance, which was not usual practice, because she had come close to a collision with USS Larson two nights before.

When the order to take up planeguard position came through, the commanding officer of Evans, Captain Albert McLemore was asleep in bed. Lieutenant Ronald Ramsey, officer of the watch, was reading, and left the maneuver in the hands of his assistant, Lieutenant Hopson. McLemore had left instructions to be awakened if there were to be any changes in the formation. Neither the officer of the deck nor the junior officer of the deck notified him when the station change was ordered. The bridge crew also did not contact the combat information center to request clarification of the positions and movements of the surrounding ships.

The Evans turned to starboard to cross in front of Melbourne. Stevenson sent a message over voice radio from bridge to bridge warning Evans that she was on a collision course, which Evans acknowledged. Melbourne radioed to Evans that it was turning to port and sounded two blasts on its siren. At approximately the same time, Evans turned hard to starboard to avoid the approaching carrier. Each ship's bridge crew claimed that they were informed of the other ship's turn after they commenced their own. After having narrowly passed in front of Melbourne, the turns quickly placed Evans back in the carrier's path. Melbourne hit Evans amidships at 3:15 am, cutting the destroyer in two.

Inquiry and Court Martial

A joint board of inquiry was established to investigate the incident, following the passing of special regulations allowing the presence of Australian personnel at a U.S. inquiry. The board was in session for over 100 hours with 79 witnesses interviewed.

Despite admissions by members of the U.S. Navy, given privately to personnel in other navies, that the incident was entirely the fault of Evans, significant attempts were made to reduce the U.S. destroyer's culpability and place at least partial blame for the incident on Melbourne. The unanimous decision of the board was that although Evans was partially at fault for the collision, Melbourne had contributed by not taking evasive action sooner, even though doing this would have been a direct contravention of international sea regulations, which stated that in the lead-up to a collision, the larger ship was required to maintain course and speed.

Two charges of negligence—for failing to explicitly instruct Evans to change course to avoid collision and for failing to set the carrier's engines to full astern—were laid, with the court martial held from 20 to 25 August. Evidence presented during the hearing showed that going full astern would have made no difference to the collision, and on the matter of the failing-to-instruct charge, the presiding Judge Advocate concluded that reasonable warning had been given to the destroyer and asked "What was [Stevenson] supposed to do—turn his guns on them?". Of the evidence and testimony given at the court-martial, nothing suggested that Stevenson had done anything wrong; instead it was claimed that he had done everything reasonable to avoid collision, and had done it correctly.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Stevenson was then subject to court martial. Two charges of negligence - for failing to explicitly instruct Evans to change course to avoid collision and for failing to set the carrier's engines to full astern - were laid. The defense submitted that there was "no case to answer" resulting in the dropping of both charges, and the verdict of "Honourably Acquitted." Despite the findings, Stevenson's next posting was as chief of staff to a minor flag officer; seen by him as a demotion in all but name. The posting had been decided upon before the court-martial and was announced while Stevenson was out of the country for the courts-martial of Evans's officers; he did not learn about it until his return to Australia.

Stevenson requested retirement, as he no longer wished to serve under people he no longer respected. This retirement was initially denied, but was later permitted.