USS Serpens: The Coast Guard?s Greatest Loss

“I felt and saw two flashes after which only the bow of the ship was visible. The rest had disintegrated and the bow sank soon afterwards.” – Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Perry Stinson, USS Serpens commanding officer

The quote above refers to the Coast Guard-manned USS Serpens. Nearly 73 years ago on January 29, 1945, a catastrophic explosion destroyed the transport. In terms of lives lost, the destruction of the Serpens ranks as the single largest disaster ever recorded in Coast Guard history.

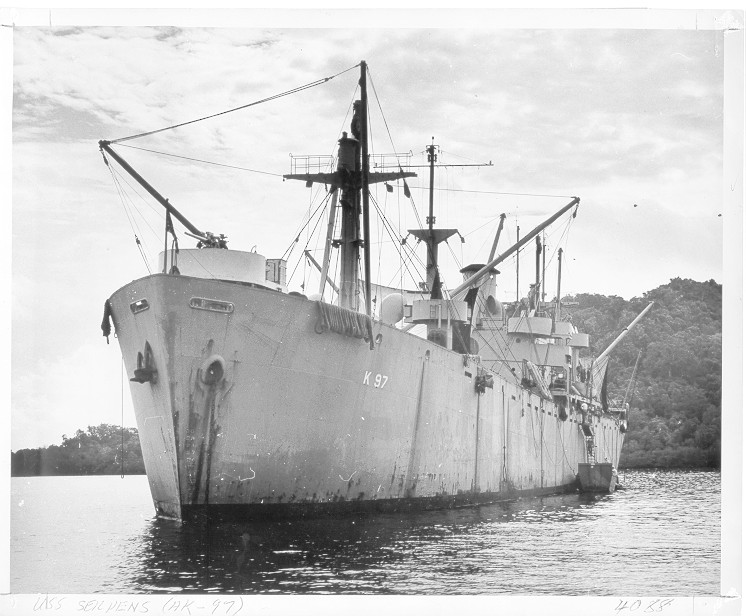

In March 1943, an EC-2 class “Liberty Ship” was laid down under a Maritime Commission contract as “Hull #739” by the California Shipbuilding Corporation of Wilmington, California. It was launched less than a month later as the SS Benjamin N. Cardozo. Two weeks later it was transferred to the U.S. Navy and designated AK-97. The transport was 442 feet in length, displaced 14,250 tons and had a top speed of 11 knots. For defense it carried one 5-inch gun, one 3-inch gun, two 40mm and six 20mm anti-aircraft cannons. Its crew consisted of 19 officers and 188 enlisted men. In late May, the Navy renamed the transport Serpens, after a constellation in the Northern Hemisphere, and commissioned the vessel in San Diego under the command of Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Magnus Johnson.

Following a shakedown cruise off Southern California, Serpens loaded general cargo at Alameda, California, and, on June 24, set sail to support combat operations in the Southwest Pacific. It steamed between the supply hub of New Zealand and various Pacific islands, such as Tonga, Vitu Levu, Tutuila, Penrhyn, Bora Bora, Aitutaki, and Tongatabu. In early December, Serpens moved its operations into the southern Solomons, re-supplying bases and units on Florida Island, Banika Island, Guadalcanal and Bougainville. In February 1944, its crew was ordered back to New Zealand for dry-dock and, for another four months, they delivered materials to bases in the New Hebrides and Solomons.

In late July 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Perry Stinson assumed command from Johnson. From that time into the fall of 1944, Serpens resumed operations carrying general cargo and rolling stock between ports and anchorages within the Solomon Islands. In mid-November, it loaded repairable military vehicles from the Russell Islands and Guadalcanal and sailed for New Zealand. After offloading in New Zealand, three of its holds were converted for ammunition stowage. Late in December 1944, Serpens commenced loading at Wellington, completed loading at Auckland, New Zealand, and returned to the Solomons in mid-January 1945.

Monday, January 29, found Serpens anchored off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal. Lunga Point had served as the primary loading area for Guadalcanal since the U.S. military’s first offensive of World War II began there in August 1942. Serpens’s commanding officer, a junior officer and six enlisted men went ashore while the rest of the crew loaded depth charges into the holds or performed their usual shipboard duties. Late in the day, in the blink of an eye, the explosive cargo stowed in Serpens’s holds detonated. An enlisted man aboard a nearby Navy personnel boat gave the following eyewitness account:

“As we headed our personnel boat shoreward, the sound and concussion of the explosion suddenly reached us and, as we turned, we witnessed the awe-inspiring death drams unfold before us. As the report of screeching shells filled the air and the flash of tracers continued, the water splashed throughout the harbor as the shells hit. We headed our boat in the direction of the smoke and, as we came into closer view of what had once been a ship, the water was filled only with floating debris, dead fish, torn life jackets, lumber and other unidentifiable objects. The smell of death, and fire, and gasoline, and oil was evident and nauseating. This was sudden death, and horror, unwanted and unasked for, but complete.”

After the explosion, only the bow of the ship remained. The rest of Serpens had disintegrated, and the bow sank soon after the cataclysm. Killed in the explosion were 197 Coast Guard officers and enlisted men, 51 U.S. Army stevedores, and surgeon Harry Levin, a U.S. Public Health Service physician. Only two men on board Serpens survived–Seaman 1/c Kelsie Kemp and Seaman 1/c George Kennedy, who had been located in the boatswain’s locker. Both men were injured, but were later rescued from the wreckage and survived. In addition, a soldier who was ashore at Lunga Point was killed by flying shrapnel. Only two Coast Guardsmen’s bodies were recovered intact and later identified out of the nearly 250 men killed in the explosion.

At first, the loss of Serpens was attributed to enemy action and three Purple Heart Medals were issued to the two survivors and posthumously to Levin. However, a court of inquiry later determined that the cause of the explosion could not be established from surviving evidence. By 1949, the U.S. Navy officially closed the case deciding that the loss was not due to enemy action but an “accident intrinsic to the loading process.”

Today, all that remains of the Serpens is the bow section sitting upside down on the sea floor off Lunga Point. The dead were initially buried at the Army, Navy and Marine Corps Cemetery at Guadalcanal. The crew’s mortal remains were later exhumed and shipped to Arlington National Cemetery for burial. On June 15, 1949, Serpens’s Coast Guardsmen were interred on Arlington Cemetery’s Coast Guard Hill. A monument to the Serpens listing all of the lost crewmembers was erected over the gravesite and dedicated on November 16, 1950.

This blog is part of a series honoring the long blue line of Coast Guard men and women who served before us. Stay tuned as we highlight the customs, traditions, history and heritage of the Coast Guard.

William H. Thiesen, Ph.D. is Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historian.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.