Photo Essay: The Fate of the Polar Sea

As the U.S. Coast Guard moves towards building a replacement for the aging heavy icebreaker Polar Star, the service is deciding whether to reactivate her sister ship, the Polar Sea, to fill the gap before the delivery of the newbuild. A new assessment provided to Congress shows that there are major obstacles to the Sea’s reactivation – namely, her propulsion, mechanical, electrical, piping and controls systems, virtually all of which would have to be overhauled or fully replaced. Based on recent official statements, it is likely that the full cost would run to the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Polar Sea was designed at the height of the Cold War, with the best of the era's technology. At the time of commissioning, she and her sister ship were advanced, capable vessels; but four decades have passed, and following a major engine casualty in 2010, her repair budget, spares and crew were all transferred to an effort to restore the Polar Star. She has been inactive since.

In September, USCG Commandant Adm. Paul Zukunft likened the Polar Sea to “an old car that's been laid up without an engine in it, an engine that's been stripped of its parts . . . it's not until you really tear into it, and what you maybe thought you could do for $100 million is now $200, is now $300, $400 and you reach a point where you keep throwing good money after bad.”

The new condition assessment confirms his impression. “The most severe challenge to both the long term sustainment of the Polar Star as well as potential reactivation of Polar Sea is the global obsolescence of virtually every system onboard,” wrote the Coast Guard’s Office of Naval Engineering. “It is abundantly clear that reactivation will entail substantially more effort and subsequent technical, schedule and cost risk than was experienced with [the reactivation of] Polar Star.”

The assessment found that only one in six of her 1,200 identified system components were supportable for five years or more.

MarEx visited the Polar Sea at Vigor Industrial in Portland, Oregon earlier this year, where the vessel had just finished a preservation drydocking period. The photos taken in her mechanical spaces illustrate some of the difficulties facing an attempt at reactivation.

Captions: USCG Office of Naval Engineering (CG-45), USCG Commander Eben Phillips

CG-45: "The two engines in Diesel 1 (machinery space), 1A and 3A, are partially dismantled, as overhaul work was halted in 2011 to conduct a root cause failure analysis. They were never reassembled."

CG-45: "The two engines in Diesel 1 (machinery space), 1A and 3A, are partially dismantled, as overhaul work was halted in 2011 to conduct a root cause failure analysis. They were never reassembled."

CDR Phillips: "When this ship was laid up she was having repeated engine failures related to wear on the liners – much of the liner's chrome had been prematurely worn away near at the top. Once you remove enough chrome, the piston's going to come up and the rings get stuck, then the rings fail or the piston splits in half."

CDR Phillips: "When this ship was laid up she was having repeated engine failures related to wear on the liners – much of the liner's chrome had been prematurely worn away near at the top. Once you remove enough chrome, the piston's going to come up and the rings get stuck, then the rings fail or the piston splits in half."

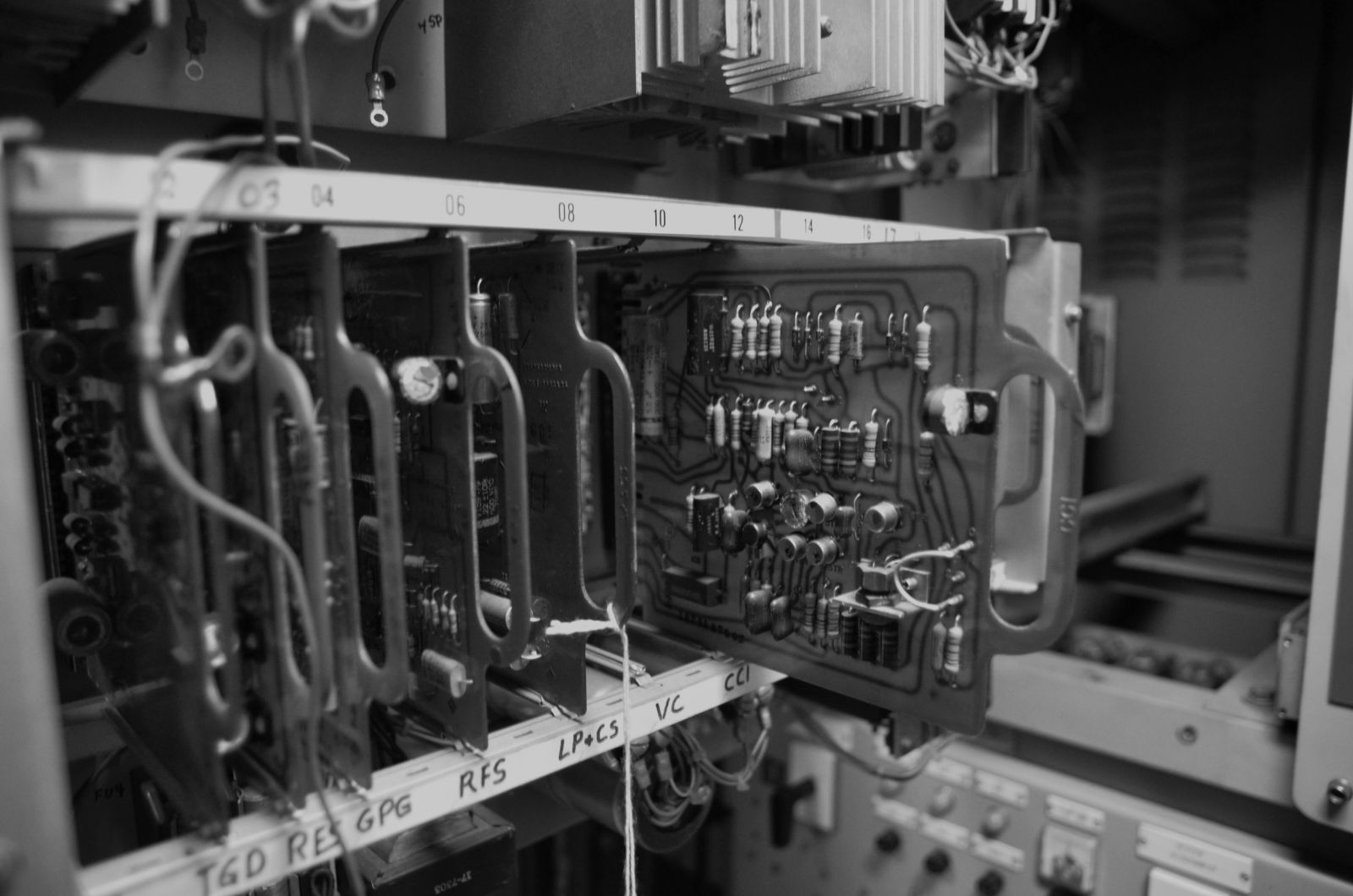

CG-45: "Polar Star's Westinghouse [propulsion control] system has been supported using system components from Polar Sea's Westinghouse system. Those parts are considered irreplaceable, and no other such parts source exists for Polar Sea."

CG-45: "Polar Star's Westinghouse [propulsion control] system has been supported using system components from Polar Sea's Westinghouse system. Those parts are considered irreplaceable, and no other such parts source exists for Polar Sea."

CDR Phillips: "We manually tune these potentiometers in port to put all the diesel-electric main engines on the same horsepower curve. And then we sail to Antarctica and hit the first piece of ice, everything here is vibrating, and the engines won't play well together anymore. This is what Polar Star is sailing with today. It's terrible – but it's a system we know, and replacing it would be difficult and risky."

CDR Phillips: "We manually tune these potentiometers in port to put all the diesel-electric main engines on the same horsepower curve. And then we sail to Antarctica and hit the first piece of ice, everything here is vibrating, and the engines won't play well together anymore. This is what Polar Star is sailing with today. It's terrible – but it's a system we know, and replacing it would be difficult and risky."

CG-45: "100 percent of the electrical cabling would require renewal to ensure it is PCB free." All electrical distribution transformers, electrical cabling and gaskets are assumed to contain carcinogenic PCBs.

CG-45: "100 percent of the electrical cabling would require renewal to ensure it is PCB free." All electrical distribution transformers, electrical cabling and gaskets are assumed to contain carcinogenic PCBs.

CG-45: "Stairtowers, passageways and red bilge paint in machinery spaces were among the areas testing positive results for lead."

CG-45: "Stairtowers, passageways and red bilge paint in machinery spaces were among the areas testing positive results for lead."

CDR Phillips: "When they reactivated Polar Star, they had one team to do retrofits and two ships to work on, so the resources for Polar Sea were reallocated. Many projects on the Sea were halted and left incomplete."

CDR Phillips: "When they reactivated Polar Star, they had one team to do retrofits and two ships to work on, so the resources for Polar Sea were reallocated. Many projects on the Sea were halted and left incomplete."

In addition to readily visible problems, the material condition assessment found hidden deterioration:

- Structural damage, consistent with the Polar Sea’s mission and age. Her “inner bottom tanks have buckled frames and bent structural members. Several deep dents were documented on the hull, especially on the port side. Cracks in overhead structural frames were documented in engine room diesel 1.”

- Piping in 11 of 80 tanks would require renewal due to wastage.

- Renewal would be required in the auxiliary seawater, fuel, ballast and fire main piping. The outmoded gravity-drain sewage system would have to be entirely removed and replaced.

- All three turbine engines would have to be replaced. All three DC electric drive motors would have to be overhauled.

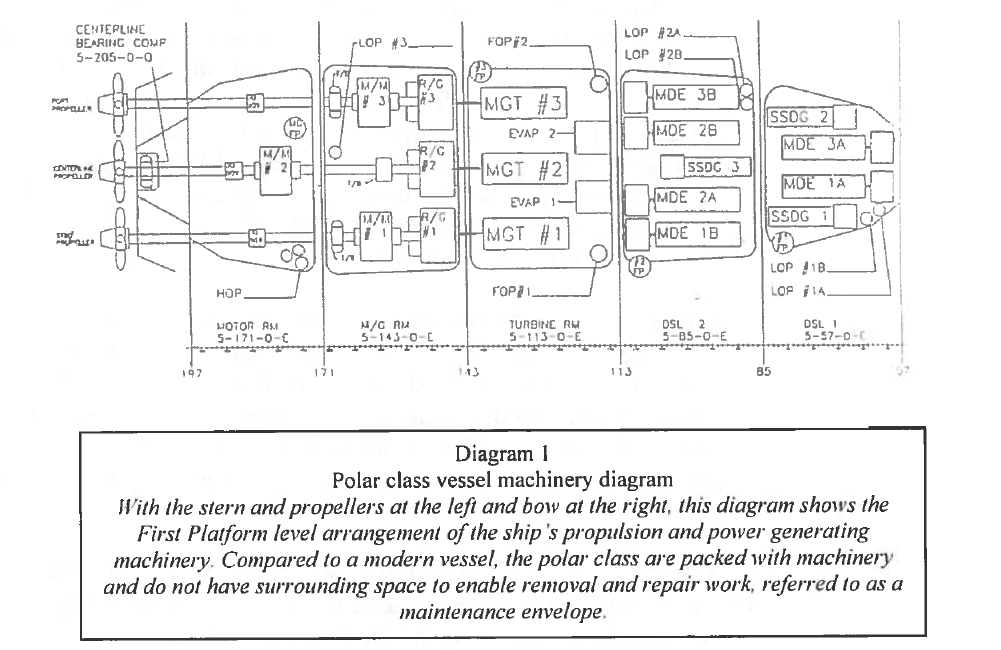

These tasks would be time-consuming and costly on any vessel, but cramped, highly compartmentalized mechanical spaces make repairs especially difficult on the Polar-class ships, as illustrated by a diagram from the assessment:

Ultimately, Congress will decide whether the USCG proceeds with reactivating the vessel, but as the Coast Guard sees it, there are only two options for filling the gap before the delivery of a newbuild, and neither is particularly attractive. Vice Commandant Adm. Charles Michel recently testified before the Subcommittee on the Coast Guard that "we have not yet identified any available multi-mission medium or heavy icebreakers suitable for military service" available for charter, anywhere in the world. He said that the only choices were either restoring the Polar Star while in service or reactivating the Polar Sea, at a yet-to-be-determined cost.

That cost estimate is due to Congress early next year –and that will likely be the point at which lawmakers decide the fate of the Polar Sea.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.