Test Facility Researchers Condemn Ballast Treatment Pessimism

We, the staff of the Golden Bear Research Center, wish to provide some perspective as a ballast water management system type-approval testing facility to an article that appeared in The Maritime Executive titled Ballast Water Treatment System Testing Under Fire on February 10.

The article, like several others to come out since the announced closing of two test facilities, accurately captured the fact that current ballast water regulations, by their specificity, encourage subjective interpretation of the regulations when considering measurement criteria for both IMO and U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) Type Approval test procedures. However, we believe the pessimistic tone regarding the apparent efficacy of type-approved ballast water management systems or the rigorousness of their testing, that has emerged as a result, is without warrant.

We agree, for instance, with Dr. Mario Tamburri that “non motility” in suitably large stationary eggs of some invertebrates would be considered compliant with the stated USCG ballast regulations for the definition of “non-living” organisms (non-motile = non-living), even though those non-motile eggs may hatch living/swimming juveniles at a later time.

We cite here another potential unsettling circumstance considering the interpretation of organism size, as it relates to ballast water discharge standards. The toxic, domoic-acid-producing, pennate diatom, Pseudonitzschia sp. (a single-celled phytoplankter), is responsible for routine shellfishery closures and marine-life kills along the west coast of North America (Scholin et al., 2004); the size of many sub-species of Pseudonitzschia is approximately 5 μm x 70 μm. According to both IMO and USCG specifications, those organisms would not be counted within the regulated size class of organisms ≥10 - <50 μm, since their minimum dimension (5 μm) is less than the regulated 10 μm limit.

It is clear to us that the international and federal ballast water discharge standards need attention/correction to modify literal interpretations of the law that seem counter-intuitive to ballast water management. However, there seems to be a swelling doomsday sentiment that examples, such as above, point to patent failure of ballast water treatment systems in the abatement of the aquatic invasive species problem.

We take objection to such a position. A global and realistic evaluation of ballast water treatment efficacy must be considered.

The global fleet of approximately 60,000 commercial shipping vessels, subject to ballast regulations, produces roughly three billion cubic meters (three billion metric tons) of discharged ballast water annually on a world-wide basis (Endresen et al., 2004). This constitutes the anthropogenic global transport vector due to ballast discharge that we are attempting to manage (ignoring the natural vector due to oceanic/coastal circulation, see below). The existing ballast water discharge standards define a line in the sand whereby an inflexible, binary judgment of pass or fail is concluded (by regulators, by extremists, by industry, by the lay population). However, the quantitative impact of ballast water effectiveness is seldom considered.

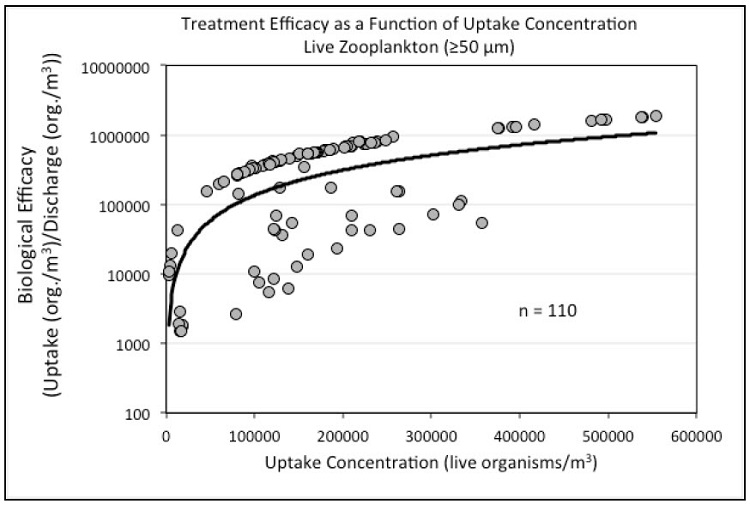

We made a recent compilation of over 100 side-by-side comparisons of the concentrations of “living” organisms pumped into our test facility during both land-based and shipboard tests in relation to the final discharge concentration of living organisms after ballast treatment; for example a simple comparison of “what goes in versus what goes out” in the figure below.

The reduction value (uptake live concentration ÷ discharge live concentration; y axis) as a function of incoming challenge concentration (x axis) ranged from 1,000 times to over 1,000,000 times; more than half of the comparisons fell in the range 100,000 times to 1,000,000 times, or, using the terminology of food and drinking water management, a 5-log to 6-log reduction in targeted organisms (log10). In fact, the actual reduction is likely larger because the data were conservatively calculated using fixed minimum detection levels in treated water even when no live organisms were observed at all.

This level of organism reduction demonstrates that ballast water treatment effectiveness is fantastically high, approaching and even exceeding the stringency required in drinking water testing/food management practices. If the global fleet of commercial vessels collectively and routinely utilized shipboard ballast water management systems, the active fleet of 60,000 ships might be reduced to an “effective” world-wide fleet of 0.6 to 0.06 ships total, using 5-log and 6-log reductions implied above.

Would we suspect shipping to be a major global vector in the anthropogenic spread of aquatic invasive species at that level?

Two sobering points must be accepted: 1) Ships must have reliable treatment systems installed and operated, routinely and collectively, to engage the global plan into action. Shipping-based species transport is a ‘give and take’ condition and all participants must be fully engaged in order to ensure the management plan operates properly. 2) A realistic acknowledgment must be given to the fact that ballast water management, even if coupled with perfect control of all anthropogenic species transport vectors (vessel biofouling, waterway construction, etc.) CANNOT eliminate the global spread of invasive species entirely; it is an abatement program, but likely not an elimination program.

A simple local example will illustrate this point. A single semi-diurnal tide cycle in San Francisco Bay floods approximately 3-4 billion cubic meters of external oceanic/coastal water through the Golden Gate daily (Conomos 1987), equivalent to, or exceeding, the total global volume of ballast water discharged annually. The point-source nature of anthropogenic ships’ ballast discharge must be managed, but the transport of aquatic species due to natural global ocean currents, riverine flow and tidal pumping will likely never be eliminated.

As all stakeholders (shipping companies, technology vendors, regulators, and testing facilities) continue to work towards effective, attainable regulations, let us remember that a one million-fold reduction in anthropogenic ballast water organism transport is cause for celebration, not criticism.

Dr. Nick Welschmeyer is Lead Scientist, GBRC Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, CSU.

Dr. Nick Welschmeyer is Lead Scientist, GBRC Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, CSU.

Christopher Brown is Scientific Program Manager, GBRC CSU Maritime Academy.

Richard Muller is Associate Director, GBRC CSU Maritime Academy.

William Davidson is Director, GBRC CSU Maritime Academy.

References

Conomos, T. J. [ed.]. 1979. San Francisco Bay: the Urbanized Estuary. Pacific Division, American Association for the Advancement of Science, San Francisco, 515p.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Endresen Ø, Behrens HL, Brynestad S, Andersen AB, Skjong R (2004) Challenges in global ballast water management. Mar Pollut Bull 48:615–623.

Scholin, C.A., (and 25 others). 2000. Mortality of sea lions along the central California coast linked to a toxic diatom bloom. Nature 403: 80-84.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.