Russia to Decommission World’s Most Remote Nuclear Power Plant

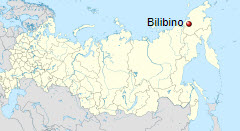

Russia’s government has approved plans to begin decommissioning what are perhaps the most secluded commercial nuclear reactors in the world, located at the Bilibino nuclear power plant in Chukotka – 5,600 kilometers and 11 time zones to Moscow’s east.

The approval represents a major step toward plugging in Russia’s controversial floating nuclear power plant, the Akademik Lomonosov, which was built to replace the electricity supplied by the Bilibino facility.

In technical terms, Russia’s nuclear utility Rosenergoatom asked for and received a license to operate the Bilibino plant’s No. 1 reactor without generating electricity for 15 years. According to Russian regulatory procedure, such a license is required before actual decommissioning work can begin.

Bilibino’s No. 1 reactor was disconnected from the power grid last March, after which its fuel was removed and placed in storage. The plant’s remaining three reactors are scheduled for decommissioning by 2022.

That’s where the Akademik Lomonosov comes in. By the end 2019, tugboats will guide the floating plant from Murmansk, were it is being fueled and tested, through the Arctic to the remote Chukotka port of Pevek, where it will plug into the local grid.

Many environmental organization’s, including Bellona, are not thrilled by this notion. The Akademik Lomosov, as a barge supporting two nuclear power units, could be vulnerable to tsunamis and other violent sea states that could waterlog its reactors. Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation, has claimed the floating plant is steeled against such calamities, citing that the Akademik Lomonosov’s has 24-hours of backup coolant should its reactor’s have to endure a Fukushima-like inundation.

Rosatom has further argued that the Akademik Lomonosov, and other floating plants it might develop, provide an essential service by bringing carbon-free electricity to faraway settlements and towns that are unreachable by more conventional power sources.

But Bellona says that this remoteness is part of the problem. The Akademik Lomosov’s location in a far-flung port makes removing and storing its spent nuclear fuel complicated and assures that any response to onboard accidents would be crippled by distance and the harsh Arctic elements of Chukchi Sea.

Still, when Rosatom said the floating plant was meant to serve a remote location, it could hardly have chosen a better area to illustrate its point.

Still, when Rosatom said the floating plant was meant to serve a remote location, it could hardly have chosen a better area to illustrate its point.

Bilibino, which Moscow classified as a town only in 1993, originally began as a gold mining outpost in the icy reaches of the East Siberian Sea. Volunteers from the Communist youth league, the Komsomol, began building the plant in 1974 – a mere four years after the Soviet post office began making regular deliveries to the area.

When it was finished in 1976, it became the world’s northernmost nuclear power plant – and certainly the only one operating in an entirely permafrost environment. The port of Pevek, where the Akademik Lomonosov will be moored, is accessible to Bilibino only by a highway built on icepack. Once the ice melts in the summer, so does the road.

The plant’s four EGP-6 style graphite moderated reactors were used to power gold and tin mining operations, which fueled a minor population boom in the 1960s. The gold prospectors and geologists moved out of their tents and into town, topping out the population at about 15,000 by the 1980s.

But the fall of the Soviet Union, and the drying up of gold reserves, brought a major decline in the town’s population, and now Bilibino is home to only about 5,000 people, the majority of whom are connected in one way or another to the operation of the nuclear power plant.

Which brings us back to the Akademik Lomonosov. With a crew of only 69, its unlikely that the floating plant will require much from local townspeople in the way of nuclear know-how and experience, certainly not enough to sustain Bilibino’s dwindling population.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Much less will the town be able to use all of the power it puts out – which Rosatom boasts is enough carbon free energy for a city of 100,000. Instead the Akademik Lomonosov will likely be used to the power numerous offshore oil drilling operations springing up in the Chukchi Sea.

This, in turn, will bring more carbon-intensive fuels to market – and will thus dismantle the last of the arguments Rosatom has made in favor of its controversial experiment in bringing nuclear powers to regions as remote as Bilibino.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.