Opinion: Russia's Arctic Gas is Funding the War in Ukraine

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the seven other member states of the Arctic Council have hit a “pause” button on cooperation. Gas from the Russian Arctic, however, is continuing to flow into Europe uninterrupted. The political theater of halting Arctic Council diplomacy will have little effect on Russia. Yet it will negatively impact circumpolar efforts on environmental, Indigenous, scientific, health, and all manner of “soft” issues. In fact, work in these areas may now be harmed twice over.

Post-invasion, Russia is raking in more money from gas exports than before

Two days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Germany froze high-profile pipeline project Nord Stream-2 (whose tangled connections to the Arctic I’ve explored about before). Yet existing gas flows have continued largely unabated from Russian pipelines to Europe, including via the Yamal-Europe pipeline, which runs through Belarus, Poland, and Germany. In the winter months leading up to the invasion, Gazprom may have been manipulating flows into Europe by withholding gas despite having a record year of both production and profits. Now, post-invasion, fighting is threatening some pipelines and causing explosions, but gas seems to be flowing relatively normally, and neither Russia nor the EU have sought to turn off the taps.

Meanwhile, the price of natural gas imports in Europe continues to rise, sending more money into Russian coffers. European think tank Bruegel estimates that Russia, the world’s largest natural gas exporter, is now raking in 500 million euros each day compared to 200 million a day in February. Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki cautioned, “We are buying, as [the] European Union, lots of Russian gas, lots of Russian oil. And President Putin is taking the money from us, from the Europeans. And he is turning this into aggression, invasion.”

Russia’s friends in Asia: China and Mongolia

Europe may be able to significantly lessen its dependence on Russian imports, estimates the think tank, Bruegel. Weighing that eventuality, Russia is looking to export of the commodity sucked out of the tundra eastward. In early February, Vladimir Putin, while meeting with Xi Jinping in China on the eve of the Olympics, announced that their two countries had inked a 30-year deal involving the annual export of 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year from eastern Siberia. This agreement builds on the 30-year gas deal signed between the two countries in 2014.

Then, four days after the invasion of Ukraine began—which China allegedly requested to be delayed until the Olympics had concluded—Gazprom’s chairman, Alexey Miller, and the Deputy Prime Minister of Mongolia signed a deal regarding the construction of the Soyuz/Vostok gas pipeline, which will run from Russia through the former Soviet satellite to China. This pipeline will be able to deliver 50 billion bcm annually. For comparison, Nord Stream 2 was planned to carry 110 billion bcm, or a little over twice as much.

Ukrainian companies, too, have their hands dirty in Arctic gas

In the middle of the pipelines stitched into Europe’s veins lies the theater of war: Ukraine. One of the main conduits transporting gas from Arctic fields to Europe is the West Siberian Pipeline. It was built at the height of the Soviet Union’s power between 1982-1984, despite strong opposition from Reagan, who was worried that it would upset the balance of energy trade in Europe. West Germany did not find Reagan’s proposed substitute sources adequate, so they supported its construction, much as they did until late with Nord Stream 2. In December 1981, the Reagan administration even sanctioned the export of large-diameter pipes to the Soviet Union, which temporarily thwarted construction. (This Russian LiveJournal blog post has an incredible story on how, post-sanctions, workers in Yamal were sent home in the frozen cold with nothing to do on New Year’s Eve but blast pipeline parts into the air as “fireworks”.) Still, the work eventually got done.

For nearly four decades now, the West Siberian Pipeline has transported gas from Urengoy, the world’s second largest natural gas field, to Uzhgorod in western Ukraine. The pipeline is partly owned and operated by Ukrainian company Ukrtransgaz. Until recently, it allegedly oversaw 50 percent of all transit of Russian gas to Europe. Ukrtransgaz is owned by Ukrainian state-owned company Naftogaz, which a French managing director at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development called “one of the darkest corners of the country’s web of corrupt interest.” In other words, certain Ukrainian companies and officials are profiting immensely from the same resources that are funding the destruction of their own country.

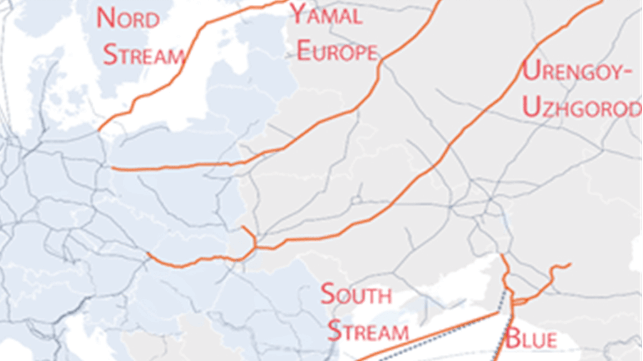

Map of pipelines connecting Russian gas fields, most of which are in West Siberia and the Arctic, to Europe. Many of these pipelines pass through Ukraine. Dashed pipelines were proposed as of 2014. Labelled locations correspond to those described in text. Pipeline data: ESRI (2014). Oil and gas data: PRIO (2009). Sea ice data: NSIC (Jan. 2022).

Map of pipelines connecting Russian gas fields, most of which are in West Siberia and the Arctic, to Europe. Many of these pipelines pass through Ukraine. Dashed pipelines were proposed as of 2014. Labelled locations correspond to those described in text. Pipeline data: ESRI (2014). Oil and gas data: PRIO (2009). Sea ice data: NSIC (Jan. 2022).

Even as Ukraine and Russia explode and implode, respectively, their wealthy and powerful citizens have a much better chance of finding safe haven from war and economic destitution than the rest of humanity. This very moment, Russian oligarchs made rich from Arctic resources are racing in the regatta of their lives to the Indian Ocean to dock their yachts in friendlier, non-Western waters. For once, they are feeling what it is like to be persecuted, and to have one’s movements constrained and conditioned by the politicking of more powerful players. To draw on Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman’s writings, the privileged move because they want to. Refugees move because they have to.

Lives upended at both ends of the pipeline

As the thirteenth day of the invasion dawns, gas continues to gush out the Arctic. Its flow is deaf to the complaints of the reindeer-herding Dolgan who live near the deposits coming onstream, to the cries of Ukrainian mothers giving birth in bomb shelters, and to the sobs of teenage Russian soldiers who claim they didn’t know they were going to war. As pipelines strangle Indigenous lands, the profits from their subterranean bounties are funding the encirclement of Ukrainian cities by Russian forces, whose soldiers are being remorselessly eviscerated with nary an acknowledgement from Putin.

The Arctic Council is pausing cooperation “pending consideration of the necessary modalities,” the seven states apart from Russia hermetically declared. But they are not pausing the purchase of commodities robbed out of the Russian Arctic, which are the source of so much regional devastation and global corruption. So long as the gas is coursing through tubes of welded steel connecting the boggy expanses of Yamal to the black soils of Ukraine, people at both ends of the pipeline will suffer.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Mia Bennett is an assistant professor in the University of Washington's Department of Geography. She researches the politics of infrastructure development in the Arctic by combining fieldwork and critical remote sensing.

This article appears courtesy of Cryopolitics and is reproduced here in an abbreviated form. The original may be found here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.