Partnering Towards Zero Emissions Shipping: Playbook Part 4

[By Mikael Lind, Wolfgang Lehmacher, Sanjay Kuttan, Jillian Carson-Jackson, David Cummins, Margi van Gogh, Torbjörn Rydbergh]

The shipping industry is accelerating its decarbonization efforts, building on past initiatives for example, (Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP), to meet more ambitious targets. The sector appreciates that effective large-scale decarbonization requires alignment and collaboration across the ecosystem. This is evidenced by various partnerships that have emerged to collectively address maritime decarbonization. This article explores the current landscape of collaboration. Is the current approach holistic and inclusive enough to achieve ambitions set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), European Union (EU), and the Paris Climate Agreement?

The decarbonization ecosystem includes the critical value chains of the maritime cluster which involves marine fuel producers and suppliers, shipbuilders, engine makers, technology providers, port authorities and operators, maritime service providers, and policy makers. Executing initiatives effectively is highly dependent on keeping the delicate balance between supply and demand subject to timeliness, scalability, and readiness. The availability of green steel, for example, will impact the shipbuilders’ efforts to build greener ships over and above the requirements set by the EEDI. Engine makers are required to provide assurance for the safe and reliable use of alternative fuels, either in current engines or future engine models, for new and retrofitted ships. The availability of alternative fuels and the operational readiness, including training, of the bunkering ecosystem to provide these new fuels is critical for the decarbonization of shipping. Ensuring optimised operations and verifying the effectiveness of decarbonization solutions, requires digital systems with strong communication networks to monitor vessel performance for fuel consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting. All this requires close coordination across the ecosystem which needs to be orchestrated.

Coordination of the stakeholders owning and driving the decarbonization initiatives is critical. These stakeholders include private and public sector actors, academia, and international, intergovernmental, and non-governmental organisations (IOs, IGOs, NGOs). Roles, responsibilities, and contributions of each actor in the initiative needs to be clarified so that each entity becomes a contributing piece of the jigsaw puzzle. As an example, where technology and policy gaps exist, the role of research in technology or regulations needs to be aligned with the objectives of the overall decarbonization efforts. While IOs, IGOs, and NGOs can initiate and facilitate the interaction between actors, it is the private sector that needs to own and execute deployment of decarbonization solutions. The various stakeholders across the value chain work together to ensure cooperation occurs on a timely basis. Primary and secondary actors work together in this orchestra of stakeholders, driven by financial contribution, regulatory compliance, and ownership of intellectual property. The nature of such relationships can range from the simple to the complex. This results in team, group, and system dynamics that requires leadership to work well.

This article builds upon the recently released Practical Playbook for Maritime Decarbonisation (Playbook), which sheds light on the type of partnerships emerging or required, and outlines the stakeholder dynamics across the maritime decarbonization ecosystem. The article also analyses different decarbonization partnerships through the lens of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal collaboration, as well as the scope of impact which can be company-focused, and / or beneficial to industry or ecosystem.

Introduction – important players along the value chains

The heterogenous range of vessel types with different designs for specific purposes creates a complexity for the deployment of low/zero carbon technologies. Therefore, setting a clear objective and outlining a business model for decarbonization efforts is an important starting point. This will determine the type of ships needed, the amount and type of fuel required, the type and size of technology to be installed, and the operational requirements. We need a new paradigm with respect to the adoption of business models with innovative technologies to effectively decarbonise the maritime sector. The new paradigm can be dubbed “Leadership through Partnership” as collaborative multi-stakeholder efforts are paramount to accelerate maritime decarbonization, through spreading risks and enhancing solutions that will fast track adoption. Enablers like port regulations and ‘just-in-time’ arrival support systems are indifferent to business model and technology, impacting all vessels almost equally.

It is the stakeholder’s responsibility to identify and activate the specific enablers that support their business model and adoption of low/zero carbon technology and practices. Enablers should be executed with the aim to make sure they are scalable in the future, which requires a well-planned and coordinated effort across value chains. Alignment is best achieved through formalised partnerships across the relevant value chains with common collaborative objectives.

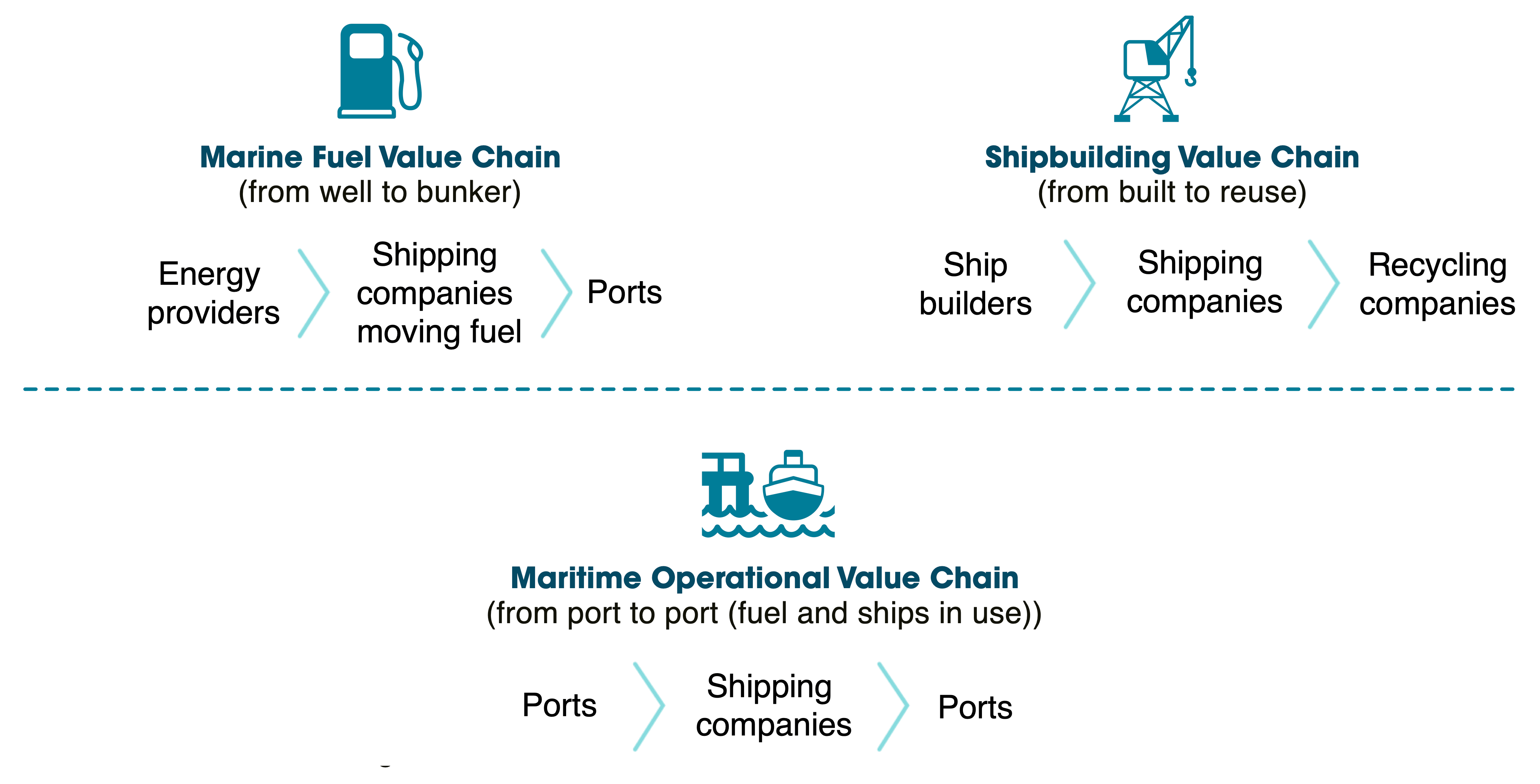

There are key stakeholders (Figure 1) with different levels of influence across the cluster of the three critical maritime value chains as well as in adjacent clusters.

Figure 1: Key players in the different value chains (Playbook graph refined)

The inclusive and consultative approach adopted by the EU and the IMO is often criticised for being slow due to the need for consensus; but once consensus is reached, implementation can then be achieved quickly. In response to these longer up-front processes, there are individual private and public sector pioneers taking the initiative by aligning with selected parties and investing in specific decarbonization enablers to give impetus - aiming to set direction and standards themselves. Examples are the creation of the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) by leading container shipping lines and the investments of Maersk Line and CMA CGM in methanol-powered ships. Shipping lines are concerned that different standards and inconsistent regulations can cause significant challenges for the industry, shippers, and beneficial cargo owners (BCOs).

The role of key influencers

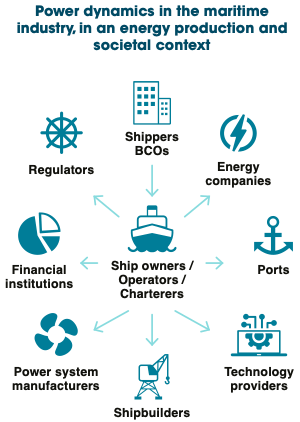

The most influential actors are those that drive the demand for clean technologies, ships, fuels, and practices. While shipowners, operators, and charterers can give demand signals, energy companies influence in turn by defining supply. Shipowners, operators, and charterers find themselves under increasing pressure from BCOs that need their help to reduce their carbon footprint. They have also appeared on the radar of national governments who seek to meet their emission targets. When shipowners, operators, and charterers move, others in the industry usually follow. As an example, ports usually store and bunker the alternative fuels their customers, the shipowners, operators, and charterers demand. Of course, there are exceptions, like MAN which has been developing ammonia powered motors before fuel stocks can be put in place. Key influencers can be instrumental aggregators of required parties from across the ecosystem.

By moving first and fast, key influencers wish to position themselves as leaders, believing that there is a ‘first mover advantage’ to be gained. The subsequent followers are made up of those wishing to proactively mitigate anticipated compliance risks and gain competitive edge. This momentum created by subsequent followers is needed to reach the tipping point of adopters triggering accelerated decarbonization.

The momentum created by first movers and by followers has been exemplified by the container shipping company CMA CGM, that recently confirmed ordering six 15,000 TEU dual-fuel methanol-powered ships hard on the heels of their peer Mærsk that had announced an order for 12 methanol-powered ships in 2021. Going forward, other players are expected to follow. Since dual fuel engines are available today, fuel manufacturers see a business case and are expected to produce the required volume of green methanol (figure 2). However, they have two main production hurdles to overcome - the availability of green hydrogen and the availability of biogenic carbon dioxide.

Figure 2: Power dynamics in the maritime industry, in an energy production and societal context

National, regional, and international regulators can accelerate decarbonization efforts by setting rules or adopting frameworks that guide industry, for example, through ambitions, targets, and obligations, such as carbon reporting. Furthermore, regulators can support private sector activities with policies and programs that stimulate investment, capacity building, and innovation in the area of green technology. Doing this effectively also requires structured collaboration and open exchange between the public and private sector. This alignment will help contextualise research projects with specific problem statements therefore engaging academia and research institutes in a meaningful way.

Positioning different partnerships

Based on a recently elaborated framework, The Maritime Decarbonisation Partnerships Matrix, various acknowledged collaborations have been positioned (Figure 3) along two dimensions; first the type of collaboration or form of partnership (vertical, horizontal, and diagonal), and second the focus of partnership looking at the beneficiaries, that is - whether companies benefit, or also industry benefits, or also other industries, the ecosystem benefits.

When positioning the various partnerships, we take a maritime industry perspective. The composition of the collaboration is the main criteria for identifying the “form”, while the beneficiaries determine the “focus”. Both types of information have been withdrawn from announcements and websites.

Partnerships without competitors fall into the “vertical” category. Where only peers are involved, partnerships fall in the “horizontal” category; and collaborations that consist of vertical and horizontal alignment are considered “diagonal”. Diagonal partnerships also contain overarching initiatives with (some) focus on the maritime sector. All three forms can and should ideally include governments, IOs, IGOs, and/or NGOs.

Vertical constructs that are built along the value chains, downstream, upstream, or a combination of both, are often initiated and driven by one single (stronger) player in the chain such as a larger shipping company. As an example, collaboration could ensure that there is sufficient supply of green methanol for ships upstream in the transportation chain which would allow a shipping company to offer downstream forwarders cleaner transport solutions enabling them to respond to such demand. Vertical arms-length partnerships can result in vertical integration where a shipping company acquires an energy provider.

Horizontal partnerships are built between peers, for example, among wet bulk carriers that aim to achieve higher asset productivity, and with that they reduce GHG emissions, costs, and delays. Horizontal alliances are usually harder to find as they require specific circumstances for example, exigencies or mutual benefits, and may need to comply with different legislative requirements. These partnerships are also governed by anti-competition laws which adds another level of complexity, albeit surmountable.

Diagonal partnerships cut across different stakeholder groups, horizontally and vertically, and usually require a neutral actor, like an IO, NGO or IGO, to make them work. Often, multiple neutral partners are involved. They can initiate multi-stakeholder partnerships by bringing together, for instance, shipping companies, energy providers, financial institutions, and governments. A good example is the Getting to Zero Coalition that is working to commercialise and scale zero emissions ships operating both along deep-sea trade routes and in shortsea through engagement with stakeholders across the maritime value chain. Diagonal partnerships can bring all relevant actors to the table to work together to identify efficient technologies or find new business models that fit with and accelerate alternative fuel uptakes, like the Mærsk McKinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping (MMMFCZCS).

A collaboration that primarily impacts the companies involved falls into “company benefits”. A partnership that helps the entire industry, for example through building a maritime bunkering hub falls into “industry also benefits”; and an alliance that impacts multiple industries, like establishing a hub for renewable energy which can be used by many industries falls into “ecosystem, also other industries and areas benefit”.

|

|

Form of partnership |

|||

|

|

A: Vertical |

B: Horizontal |

C: Diagonal |

|

|

Focus of partnership |

1: Primarily participating companies benefit |

CMA CGM biofuel trial Singapore; |

Tankers International VLCC Pool

|

|

|

2: Industry also benefits |

Maersk green methanol partnership;

CMA CGM / TotalEnergies ship-to-ship LNG bunkering with the goal to establish a Mediterranean maritime LNG hub at Marseille-Fos Port

|

Digital standards (as one area of focus) in

|

Getting to Zero Coalition (Global Maritime Forum / World Economic Forum); The Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation (GCMD); Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping; Blue Sky Maritime Coalition; PIONEERS; MAGPIE |

|

|

3: Ecosystem, also other industries and areas benefit |

Maersk / Egypt green energy partnership

|

None identified yet

|

Renewable and Low-Carbon Fuels Value Chain Industrial Alliance;

|

|

Figure 3: Contemporary partnerships populated in the Maritime Decarbonisation Matrix

We found several examples of vertical collaborations focusing on decarbonising individual value chains producing primarily benefits for the companies involved (A1), such as the CMA CGM biofuel trial in Singapore. There are also vertical collaborations also creating value for the maritime industry (A2), such as the partnership between AP Møller-Mærsk and renewable energy firm Ørsted on a new Power-to-X facility in the United States of America (USA) to produce zero emission maritime fuels. An example of a vertical partnership with impact on ecosystem level is the Mærsk / Egypt green energy partnership that supports the Egyptian government to position Egypt as a global hub for renewable energy (A3).

An example of a horizontal partnership focussed on a single maritime value chain (B1) is the Tankers International VLCC Pool bringing together peers in a joint pool of resources of wet bulk vessels. Examples of horizontal partnerships benefitting the maritime industry (B2) are the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) created by major container shipping lines to develop standards to increase the fluidity and efficiency of the sector and thus reduce GHG emissions, costs, and delays, and the International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH) with their initiatives on decarbonising their industry. We have not yet identified an industry-driven or overarching horizontal partnerships also focussing on the ecosystem (B3).

Diagonal partnership on different levels have emerged with the Project Sabre Consortium focussing primarily on company benefits (C1) through the ammonia bunker supply chain. There are several diverse diagonal initiatives focused on the decarbonization of the maritime industry (C2), such as the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation (GCMD) in Singapore, the Blue Sky Maritime Coalition, and the Global Maritime Forum, with the Getting to Zero Coalition pursued in collaboration with the World Economic Forum which brings together “more than 150 companies within the maritime, energy, infrastructure and finance sectors, supported by key governments and intergovernmental organisations” that have prepared a roadmap containing the necessary steps from developing and testing solutions and enabling environments to getting ready for roll-out. Last but not least, there are also diagonal partnerships that focus on the ecosystems (C3), such as the Mission Possible Partnership, the Renewable and Low-Carbon Fuels Value Chain Industrial Alliance, Mission Innovation, and the Horizon 2020 maritime / port decarbonization initiatives PIONEERS and MAGPIE.

Diagonal partnerships that directly benefit the maritime industry and the broader decarbonization ecosystem (red rectangle in Figure 3) are paramount to avoid misalignment of decarbonization actions. Some stakeholders engage in multiple partnerships which may differ in form and/or focus.

Engaging actors along the entire distribution curve

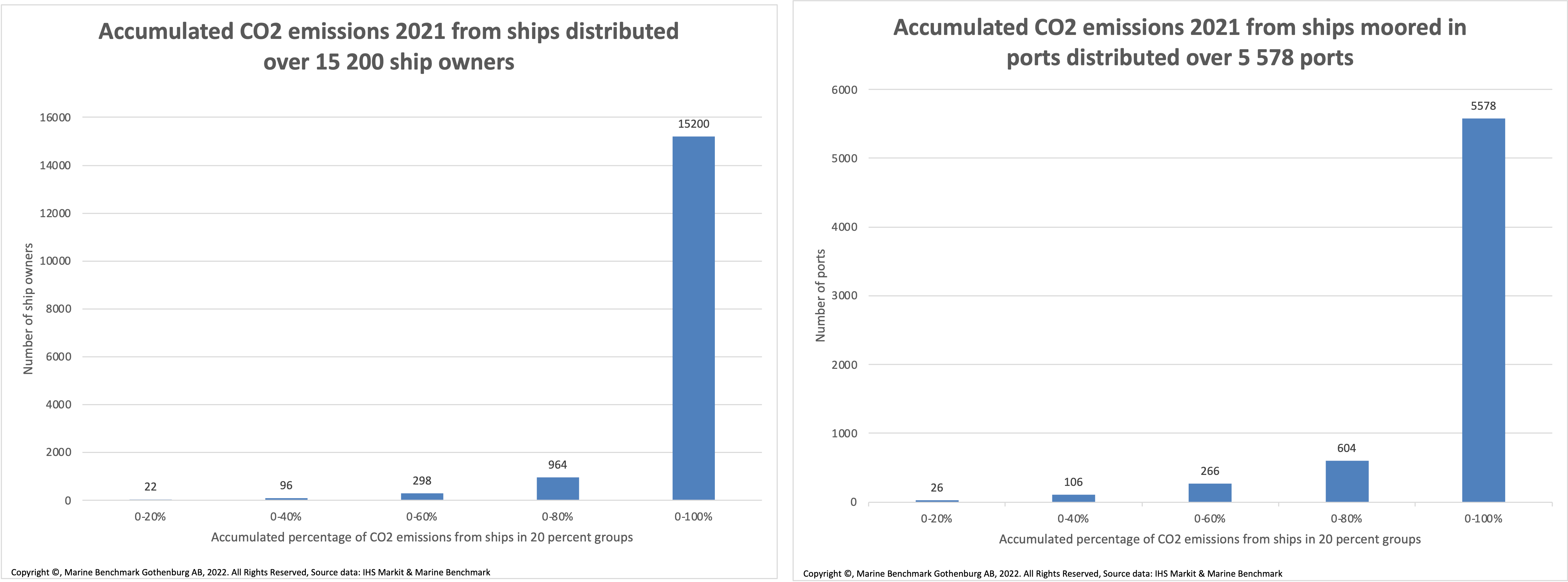

None of the identified decarbonization partnerships include the long tail of smaller enterprises. In 2021, about 54,000 cargo and passenger vessels that travelled the oceans were owned by approximately 15,200 companies. 22 larger players (less than 0.15 %) owned 3,355 ships (about 6.2 %) representing 20 % of the CO2 emissions, and 964 players (about 6.34 %) owned 24,907 ships (about 46.1 %) representing 80 % of the CO2 emissions. The situation with ports is similar. Out of the 5,578 ports that have served the merchant fleet, only 26 (less than 0.5 %) were responsible for 20 % of CO2 emissions from moored cargo and passenger ships (figure 4). The 747 million tonnes of CO2 emitted by the merchant fleet include 47 million tonnes (about 6.3%) generated during mooring.

Figure 4: Accumulated CO2 emission from cargo and passenger vessels grouped by number of ship owners and ports (during mooring) during 2021 (source: Marine Benchmark)

Achieving the maritime industry’s ambitious decarbonization objectives requires that we look at both, the larger and the smaller players. The economies of scale generated by the partnerships of larger companies may also have a positive impact on the smaller actors. Nevertheless, the larger player-led decarbonization partnerships should find ways to include the smaller companies. The MMMCFZCS seeks decarbonization solutions and best practices to make them available to all. The Center is also working on a Nordic-Baltic green corridor and on a book & claim system attractive for smaller players that cannot have or afford to administer their own mass-balancing system offering green services to customers. The GCMD on the other hand ideates, curates and finances pilot / demonstration projects that help address complex system level challenges that engages the entire value chain, and that will benefit the industry. Curating like-minded players large and small that have clear roles in these projects is important to ensure an effective collaborative effort. Long tail actors could be further engaged through a digital interface that helps bringing smaller companies onto digital partnership platforms at a lower participation cost, thus enabling them to easily provide input and let them in turn benefit from the output of other participants. On such platforms, new approaches like open and collaborative innovation can help to complement the current work. Smaller and larger actors benefits from initiatives like the Data for Common Purpose Initiative that engages private and public sector to build data sharing frameworks.

Conclusions – holistic and inclusive approach

We are pleased to acknowledge that the maritime industry has been progressing. Pioneers have emerged and triggered followership giving birth to a decarbonization movement in the maritime sector. Now, the immediate goal is to reach the critical mass of stakeholders that support the initiatives that accelerate GHG emissions reductions.

Context matters. In the Playbook, we have outlined three maritime transition scenarios using nautical terms as a metaphor: Swells, where wealth is prioritised first; Storms, where autonomy is prioritised first; and Clear Sky where well-being is prioritised first. All scenarios are plausible and part of our current reality. Swells stands for the capitalist world that brought our current wealth but also unwanted consequences, Storms stands for the decoupling between the East and the West, and Clear Sky manifests itself in many examples of decarbonization initiatives taken. In all these worlds, each form of partnership has a role to play to drive decarbonization. Vertical partnerships work best in Swells as they follow the spirit of competitive advantage but will hardly exert the required large-scale impact on industry and ecosystem. Horizontal partnerships help the industry to prepare for a world of Storms; the global shipping industry is well positioned to overcome barriers and avoid multiple standards and inconsistent regulations across the globe provided it gets aligned. Diagonal partnerships are most compatible with the Clear Sky scenario as only diverse groupings allow for broader industry and ecosystem decarbonization.

Reaching or even exceeding the IMO 2018, EU, and Paris Climate Agreement ambitions requires a holistic and inclusive approach. Whilst the holistic angle is reflected in current efforts, inclusiveness is lagging. This contribution aims to offer a practical guide to help the shipping industry refine its collaboration approach embracing partnerships which also include the smaller players that populate the long-tail of the distribution curve of maritime companies.

About the authors

Mikael Lind is the world’s first (adjunct) Professor of Maritime Informatics and is engaged at Chalmers, Sweden, and the Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). He serves as an expert for World Economic Forum, Europe’s Digital Transport Logistic Forum (DTLF), and UN/CEFACT. He is a well-recognized trade press author, the co-editor of the first two books of maritime informatics, and co-author of the recently released Practical Playbook for Maritime Decarbonisation.

Wolfgang Lehmacher is operating partner at Anchor Group and advisor at Topan AG. The former head of supply chain and transport industries at the World Economic Forum, Geneva and New York, and President and CEO Emeritus of GeoPost Intercontinental, Paris, is advisory board member of The Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society, Singapore, ambassador of The European Freight and Logistics Leaders’ Forum, Brussels, advisor of GlobalSF, San Francisco, founding member of the think tanks Logistikweisen, Germany, and NEXST, Singapore, and co-author of the recently released Practical Playbook for Maritime Decarbonisation.

Dr Sanjay Kuttan is currently the Chief Technology Officer of the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonisation. He has also been with the Singapore Maritime Institute and the Nanyang Technological University. His experience in the private sector has primarily been in the oil and gas, as well as energy sectors. He also serves as a council member of several Energy related Associations.

Jillian Carson-Jackson is the immediate past president of The Nautical Institute, a Director of GlobalMET, an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, the Chair of the IALA ENAV Committee Working Group on Emerging Digital Technologies and an advocate for maritime informatics.

David Cummins is President and CEO of the Blue Sky Maritime Coalition. Cummins previously worked as an executive with Shell with more than 35 years’ experience covering many locations around the world as well as many diverse businesses and skill areas including shipping and maritime commercial & business development, global strategy development & implementation, and change management.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Margi Van Gogh leads the Supply Chain & Transport (SCT) Industries portfolio at the World Economic Forum, centred on accelerating transitions to safer, cleaner, more inclusive global transportation systems. SCT initiatives harness private and public collaboration, delivering impact through systemic transformation to generate economic, environmental, and societal value.

Torbjörn Rydbergh is founder and Managing Director of Marine Benchmark and has a M. Sc in Naval Architecture from Chalmers and has been in the shipping and car industry for the last 25 years. He has worked for IHS Markit, Lloyd’s Register, and Volvo Cars among others.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.