Op-Ed: Russian Hypocrisy and "Unlawfare" in the Black Sea

[By Dr. Ian Ralby and Col. Leonid Zaliubovsky]

Despite Russia continuing to bomb civilians and target hospitals amid an aggressive war that is itself illegal, the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) has taken the time to issue a press statement complaining about Ukrainian mines in the Black Sea. Specifically, the FSB claims that the Ukrainian Navy has violated international law because a storm broke loose some of the submarine mines used to protect Ukrainian ports from the Russian invasion. Interestingly, Russia is claiming that Ukraine has contravened the provisions of the 1907 Hague Convention (VIII) on submarine mining, yet neither Russia nor Ukraine is actually a party to that Convention.

Beyond the obvious efforts at controlling the narrative, this latest statement indicates that, even while waging a brutal kinetic war, Russia is continuing its longstanding campaign of what has been termed “lawfare” – using law or legal processes to accomplish what would otherwise be military ends. In Russia’s case, however, this sort of legal bullying on the grounds of baseless legal claims and “fake law” is perhaps better termed “unlawfare.” Only by highlighting absurd legal postures by Russia and applying sound legal analysis can this nefarious tactic be effectively countered. Russia cannot be allowed to use spurious legal justifications to undermine and degrade the rule of law.

Submarine Mines

In 1898, Russian Tsar Nicholas II proposed a multinational conference to codify the laws and customs of war, initiating a process that started in the Hague and continued decades later in Geneva. The resulting conventions are the main laws that govern the conduct of states in armed conflict.

The First Hague Conference, which intentionally began on the Tsar’s birthday, was held in 1899 and resulted in three conventions and three declarations. Inspired by that success, United States President Theodore Roosevelt proposed a second Hague Conference in 1904, but it ended up having to be delayed until 1907 because of the Russo-Japanese War. The Second Hague Conference actually produced 13 conventions and a declaration. Among them, Hague VIII set forth the laws relating to the “Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines.” Significantly, the Russian Empire, which initiated the whole process and for which the Second Conference was delayed, adopted 10 of the 13 Hague Conventions of 1907, but intentionally did not sign and ratify Hague VIII. After the fall of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union reconfirmed its ratification of those 10, but again did not sign or ratify Hague VIII. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation reconfirmed its ratification of those 10, but yet again did not sign or ratify Hague VIII. At the same time, independent Ukraine also reconfirmed ratification of those same 10 conventions, but also did not sign or ratify Hague VIII. It is thus fascinating that, with all this history, Russia is now alleging a violation of a law that was rejected by both the USSR and the Russian Empire, and using that as a tactic amid a military campaign bent on restoring President Vladimir Putin’s glorified notion of Soviet and Russian Imperial greatness.

The incongruity of Russia’s argument notwithstanding, it is worth evaluating the substance of the claims as if the Hague VIII Convention did apply, as many legal scholars would suggest that both Hague VIII and the 1994 San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea are articulations of the applicable laws and customs of war to which all states are bound. According to the FSB, the Ukrainians placed old Soviet-era mines, made in the first half of the 20th century, in areas around key port cities. Since Ukraine notified Russia of the laying of these mines and none of them are either in neutral waters or blocking ships in neutral waters from accessing international waters, there is no inherent legal problem with this portion of the claim.

The FSB further claims that because of a storm, the lines holding some of the mines to their anchors broke, leaving the mines to float. Beyond prohibitions against floating mines – with limited exceptions – the San Remo Manual does clarify that “the parties to the conflict shall not lay mines unless effective neutralization occurs when they have become detached or control over them is otherwise lost.” Russia is claiming that these detached mines are now floating, not neutralized, and therefore pose a direct threat to the safety of shipping – the main concern expressed in Hague VIII.

Before examining the credibility of the Russian factual claim – a necessity with any public statement from the FSB – applying the law to the Russian allegation shows some key weaknesses. The main problem with this argument for Russia is that the only maritime activity in the area is either Russian warships or merchant vessels supporting the Russian war effort, both of which are legitimate military targets. With one key exception, commercial shipping in the area has effectively ceased because of the conflict. There has to be actual harm or threat of harm that would violate the law for there to be a real legal issue in the current context. At the moment, the main danger of the mines is to ships that the Ukrainians could lawfully target. So at best – assuming that the facts are as stated by the FSB and assuming that Hague VIII is applicable – the Russian legal claim is heavily mitigated by both the cessation of commercial shipping and Russia’s lack of standing to assert a violation.

While it is true that almost all commercial traffic has ceased, there are nevertheless roughly 100 foreign commercial vessels in Ukraine currently trapped by the conflict. Russia’s blockade has made it impossible for them to leave and safety concerns have made the situation particularly challenging for shipowners. Interestingly, Russia, after making the claim about the danger of floating mines, has begun to transmit on VHF channel 16 – the international distress frequency – that they can “guarantee” safe passage to the merchant vessels trapped in Ukraine. This offer of benevolent assistance is in direct contradiction to the expression of concern. In other words – either the claim about the floating mines is false, or the “guarantee” of safe passage is false; they cannot both be true.

Furthermore, Russia’s legal claim is based on “facts” which it has unilaterally asserted and which cannot be verified by the Ukrainian Navy. Given Russia’s obvious lack of concern for civilian life as well as its long history of false narratives grounded in fake stories and disinformation, it would not be unreasonable to question whether the present claim may also be a Russian fiction. Indeed, the credibility of the “facts” as stated by the FSB is actually undermined by the concern raised in their press statement that the mines may drift all the way across the Black Sea, through the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits and into the Mediterranean Sea where they could harm commercial shipping there. In trying to mimic concern for human life and shipping, the FSB raised alarm about an eventuality that is factually almost impossible. As such, either the entirety of the Russian claim should be disregarded until there is evidence that there are actually loose mines or Russia should welcome a NATO Mine Countermeasures Group to neutralize the threat about which the FSB is so concerned. Only with actual facts, rather than Russian assertions, can the legality of the claim can be accurately assessed.

Inconclusive at best, the legal claims of Russia do stand out as a fairly obvious form of bullying. The aim is to disrupt Ukrainian thinking, sow seeds of doubt, tarnish Ukraine’s image, and put Ukraine on the legal defensive, even in the face of a wide array of egregious legal violations by Russia. Accusations of illegality are a common tactic by criminals seeking to avoid attention for their on illicit conduct. When Major General Charlie Dunlap of the U.S. Air Force coined the term “lawfare,” he only partly envisioned this form of legal argument to achieve what would otherwise be military objectives. While it is possible to actually use the law to obtain military advantage, Russia so often resorts to fake law that its approach really is better described as “unlawfare.” For example, in Crimea, Russia has long been claiming the legal rights afforded to an occupying power (including the suspension of innocent passage) while also claiming the mutually exclusive rights of a sovereign coastal state.

The HMS Defender incident on June 23, 2021 was partly born of this legal prevarication. The British warship Defender – whose position had previously been spoofed to indicate it was at the mouth of the naval base in Sevastopol when in fact it was in port in Odessa – was transiting Crimea toward the eastern Black Sea when Russia used both surface vessels and aircraft to confront it and order it to leave. Such a demand is incompatible with the law of innocent passage and thus inconsistent with Russia’s assertion that Crimea is actually Russian territory.

So this claim about mines that have broken lose in a storm being a violation of a Convention to which neither of the belligerent states is a party needs to be viewed against the wider backdrop of Russian illegal activity. It is important to remember that Russia has been violating international law continuously since the 24th of February with an aggressive war in contravention of article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter. Furthermore, in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, Russia has proceeded to violate various laws throughout many of its naval actions. Even just looking at the most high-profile naval incidents shines a light on the extent to which Russia can only be considered a hypocrite when accusing other states of legal violations.

Russian Hypocrisy: Violations of the Law

Since the invasion on February 24, only a few maritime incidents have garnered significant external attention. The inspiring resolve of the Ukrainian Border Guard forces facing down a Russian warship on Snake Island was probably the most visible, and the loss of a Ukrainian warship that previously served as a U.S. Coast Guard Cutter far less so. A closer look at each incident would reveal a Russian proclivity for bending, breaking, and bastardizing the law. While the catalogue of Russian legal violations is long and growing, it is interesting that just focusing on these two highly publicized incidents shows just how hypocritical Russia’s claims about the submarine mines are.

Snake Island

In the Snake Island incident, the Russians not only took the Ukrainian Border Guard as prisoners of war, but also captured the crew of a civilian search and rescue (SAR) vessel and are also holding them as prisoners of war. The Border Guard, which falls under the command of the Ukrainian Navy in wartime, are, per se, combatants under international humanitarian law and the law of armed conflict. The situation with the SAR vessel, however, is legally problematic for the Russians. Under article 27 of the Second Geneva Convention, SAR vessels are afforded the same protections as hospital ships, as set out in article 22 of that Convention.

While article 22 requires a 10-day notification to the belligerent party (i.e. from Ukraine to Russia) about the use of a ship as either a hospital ship or in this case a SAR vessel, the incident occurred fewer than 10 days into the conflict. Given however that the vessel was used as a SAR vessel prior to the outbreak of the conflict and is actually labeled as a “SAR” vessel, the Russians would be deemed to be on notice. Furthermore, article 18 of the Convention requires belligerents to “without delay, take all possible measures to search for and collect the shipwrecked, wounded and sick, to protect them against pillage and ill-treatment, to ensure their adequate care, and to search for the dead and prevent their being despoiled.” Taking the civilian SAR crew as prisoners of war, therefore, is a violation of the law – a part of the story that has not garnered much attention, but that shines a light on Russia’s seeming disregard for civilian protections at sea almost as much as its disregard for civilian life on land.

The Demise of the Sloviansk

The sinking of the Sloviansk – formerly the USCGC Cushing – by an air-to-surface missile on March 3 occurred amid what the Russians were calling an “anti-terrorism” campaign in the territorial sea around Ukraine. While the Russian Duma has passed legislation authorizing Russian forces to conduct such operations abroad – outside of Russian territory – there is limited legal right under international law for Russia to conduct such operations. In peacetime, it would be a very difficult legal case to show ample evidence that attacking a foreign warship in a foreign sovereign state was a justifiable exercise of self-defense from terrorism. But Russia is already engaged in an international armed conflict in Ukraine, meaning that the lex specialis of the law of armed conflict applies. Russia did not need to use a justification of “anti-terrorism” to target a Ukrainian warship – it is an acceptable military target in a military campaign. Yet it is the narrative that was used to justify the operation that sank a Ukrainian naval vessel at a time when Russia is making little effort to explain the unlawful targeting of civilians.

Again, Russia is using mutually exclusive legal arguments, and trying to control the narrative as well as the battlespace. This blending of naval warfare with a baseless strategic communications campaign shows that, to Russia, this conflict is as much or even more about the story as it is about reality.

Russia’s Latest Illicit Naval Activity

Interestingly, beyond these two incidents and many others that have not received external attention, the Russian Navy is engaging in a wide range of activities at sea with dubious legality. Perhaps the most striking is that, as of March 13th, the Russian Navy has begun to paint out the hull numbers and names of its warships and remove the vessels’ flags, leaving no markings of nationality.

Image provided by the Ukraine Navy showing a Russian Warship – a Ropucha Class Landing Ship – underway with its hull number painted out. (Ukrainian Navy photo)

Image provided by the Ukraine Navy showing a Russian Warship – a Buyan Class Corvette – underway with its hull number painted out. (Ukrainian Navy photo)

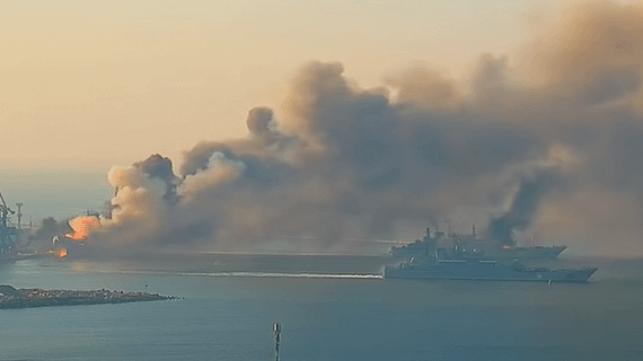

Photos from State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, released March 21, 2022, showing Russian warships with hull numbers painted over. (State Border Guard Service of Ukraine photo)

The grey hull is an indication that the vessel is a warship, but the potential delay in confirming the identity of the ship could provide Russia with an advantage. The Russian Navy may be seeking to avoid Ukrainian firepower by trying to get the Navy to hesitate in firing upon an unmarked ship. Furthermore, if the Ukrainian Navy were to sink one of these nameless, numberless, flagless warships, the Russian Navy could deny that it had lost a ship, and without an investigation, no one would be able to conclusively say which ship had actually been sunk. Given Russia’s proclivity for fiction, it could also assert that the Ukrainians had violated international law by sinking a civilian vessel, as it could not be conclusively identified as a warship.

This muddies the waters of the conflict, and intentionally creates confusion. It is raises questions about a number of laws, including the provisions relevant to a warship under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 29) and the principle of distinction, referenced in article 2 of the Hague Convention (VII) on Conversion of Merchant Ships of 1907, to which both Russia and Ukraine are parties. The specific identification of a warship by flag and hull marking is ingrained in the law of armed conflict, at least in so far as concerns the launch of an attack by a warship. This tactic by Russia of both painting over the hull numbers and vessel names of any vessel class with multiple ships and removing the flags on the vessels, is likely beyond what is permissible as camouflage or a “ruse” under international law. The launch of an attack while flying a false flag is expressly outlawed, so Russia may be trying to skirt the law with a “no flag operation.” But that still calls into question whether Russian ships without a flag could lawfully commit any belligerent act. It may also be an attempt to tee up a “tu quoque” defense as was used during the Second World War to excuse German Admiral Karl Doenitz from the charge of waging a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, as American Admiral Chester Nimitz had waged one as well. Russia may want to argue that an attack on one of its unmarked grey hulls excuses its own failure to follow the principle of distinction, thereby negating any Ukrainian claims that Russia has unlawfully targeted civilians.*

Conclusion

As President Putin proceeds in his quest to restore his idea of the Russian Imperium, it is important to continually evaluate Russian claims and highlight their flaws so as not to fall victim to any of the false narratives on which this campaign is predicated. For the FSB to use dubious “facts” to claim that Ukraine has violated a law that the Russian Empire, Soviet Union, Russian Federation, and Ukraine have all rejected is an indication that Russia does not expect anyone to actually check the veracity of its assertion. But a constant reality check shows that, objectively, Russia is an outlaw state, engaged in both continual and episodic violations of the laws and customs of war, and should not be allowed to gain any advantage when resorting to “unlawfare.” As much as Russia’s assault on Ukraine must be countered, so too must its assault on the rule of law.

Dr. Ian Ralby is a maritime lawyer and CEO of I.R. Consilium, a family firm with leading expertise in maritime and resource security.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Col. Leonid Zaliubovsky is the Head of the Legal Branch of the Ukrainian Navy Command.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.