NOAA Ramps Up Use of Airborne and Maritime Drones for Hurricane Season

NOAA and partners are improving hurricane forecasting by harnessing the power of new technologies and working to coordinate these technologies to predict hurricane track, intensity, and rapid intensification.

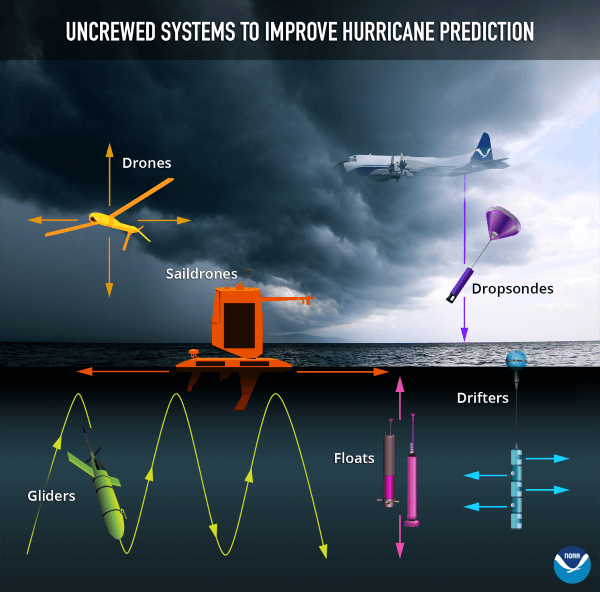

Uncrewed systems and other tools are gathering data at different levels of the ocean and the atmosphere that are key to understanding how storms form, build, and intensify. Together with NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft carrying sensors, this data paints a clearer picture for scientists of the forces that drive hurricanes. Predicting these changes in hurricanes enables communities to better prepare, which can protect lives and property and strengthen local economies.

The goal of developing new systems is that the data collected can improve the representation of the ocean and atmosphere in hurricane forecast models. Data collected by NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft using existing observational tools, such as tail doppler radar and dropsondes, has already significantly advanced NOAA forecast models.

NOAA’s newest hurricane model will go into operation this season, the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System. HAFS, NOAA’s next-generation hurricane model, aims to provide reliable forecast guidance on tropical cyclone track, intensity, and structure to NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. The model was jointly developed, tested, and evaluated by NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory, NOAA National Weather Service’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction, and NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine & Atmospheric Studies and the University of Miami.

Here are some of the new technologies that were on display Tuesday, June 27, alongside NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft at the kickoff event at NOAA's Aircraft Operations Center in Lakeland, Florida,. The new systems, many that are still being tested by researchers, are expected to complement and build upon the key observations already being collected by NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft and NOAA satellites.

This image shows NOAA Hurricane Hunters and several of the air and ocean drones, gliders, dropsondes and other technologies NOAA is using to gather data at different layers of the atmosphere and ocean to improve hurricane forecasts. Credit: NOAA

Small uncrewed aircraft systems

This spring, NOAA tested a small uncrewed aircraft system from Black Swift Technologies called the S0. The Blackswift S0 is a smaller, more lightweight uncrewed aircraft system than NOAA has used in the past with sensors that measure temperature, pressure and humidity. The tests were conducted from NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center and are a critical step in ensuring that the instruments perform their data collection tasks in a safe and effective manner during hurricane season.

NOAA will also test the use of other small uncrewed aircraft systems, working with Andruil - Altius 600 which was flown into the eye of Hurricane Ian last year, and Dragoon, which offers a land-launched small uncrewed aircraft system.

Ocean surface and subsurface uncrewed systems

For the third year, NOAA and Saildrone Inc. will deploy Saildrones, uncrewed surface ocean observation platforms powered by solar, wind and wave energy, to track Atlantic hurricanes. These robots provide information about the ocean and atmosphere, including sea surface temperature, salinity, surface air temperature, humidity, pressure, wind direction and speed, and wave height. Twelve saildrones, more than ever before, will be on patrol this summer in the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, with several providing collocated observations alongside underwater gliders.

NOAA and partners will also deploy gliders in the ocean in areas where hurricanes traditionally track. Underwater gliders are autonomous platforms that profile water properties in nearshore and open ocean environments, providing temperature and salinity observations to depths of 1000 meters, which is slightly more than a half mile, in areas where hurricanes are known to intensify and/ or weaken. NOAA and its many partners will deploy approximately 30-40 underwater gliders this season. NOAA and partners have monitored ocean conditions using gliders for more than 10 years.

These new and traditional observing systems join two other ocean-sampling sensors that NOAA has used year-round for many years. Argo floats are autonomous profiling instruments deployed across the global ocean. In the Atlantic Ocean basin they provide temperature, salinity, and pressure profiles as they drift with the currents and move vertically through the water column. Drifters are satellite-tracked surface drifting buoys that provide in-situ observations of mixed layer currents, temperature, atmospheric pressure, winds, waves, and salinity. An array of drifters is distributed across the Atlantic basin.

Data from the gliders, drifters, and Argo floats are transmitted via satellite to the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Telecommunications Center. This information is used in NOAA’s operational and research forecast models as well as many other forecast models around the world. Data from Saildrones are provided to NOAA scientists and are being used by NOAA to advance research on hurricane forecast models. Data from small uncrewed aircraft systems are also used by NOAA to advance research on forecast models.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

As many of these new systems are being tested and developed with the goal of putting them in operations, NOAA continues to rely on Hurricane Hunter planes equipped with fully operational Tail Doppler Radar which pinpoints where the strongest winds are located, how far they extend outward from a storm’s center, and the regions of heaviest rainfall. This data also enables forecasters to observe changes in intensity and storm structure, giving us a three-dimensional view of the wind and rainfall from just above the ocean surface to the very top of the storm. Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer, another operational remote sensing system on board NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft, measures surface winds inside storms.

This article appears courtesy of NOAA and is reprinted here in abbreviated form. The original may be found here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.