The Maritime Ecosystem Needs Innovation to Avoid "Paving the Cow"

by Mikael Lind, RISE (Research institutes of Sweden), Hanane Becha, UN/CEFACT, André Simha, MSC (Mediterranean Shipping Company SA), Steen Erik Larsen, A.P. Moller – Maersk, Eyal Ben-Amram, ZIM, and David Marchand, Traxens

Introduction: Paving the cow paths or innovating the ecosystem?

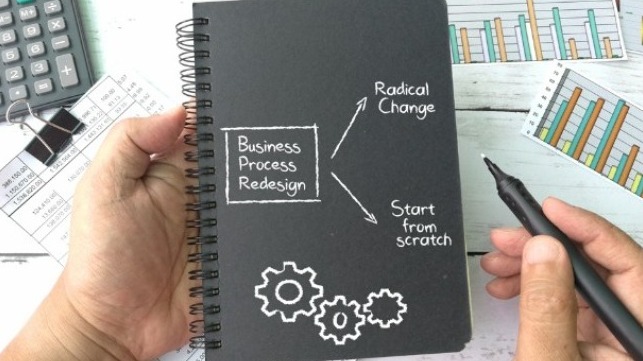

Numerous initiatives building upon digitalization, standardization and collaboration are now underway to increase the efficiency and sustainability of maritime transport. Areas of focus have been to enhance the synchronization and connectivity between ship and port operations as well to assure visibility of the status and conditions of the goods being transported - all based on data sharing. Emerging regulations on data sharing are expected to boost this interaction, but to ensure a truly beneficial change there are other initiatives that need to be taken to avoid simply using new technology to replicate out of date practices or “pave the cow paths”, as described by Professor Michael Hammer of MIT in 1990. This professor and founder of business process reengineering formulated “Instead of embedding outdated processes in silicon and software, we should obliterate them and start over. We should reengineer our businesses: use the power of modern information technology to radically redesign our business processes in order to achieve dramatic improvements in their performance.”.

In particular, we need to move beyond the individual actor view that has previously predominated in maritime transport to a more collaborative, data sharing approach. Efforts are now being taken to better synchronize by:

- increasing the interaction between what happens at sea and in ports, to allow for just-in-time arrivals

- enabling autonomous shipping by introducing capabilities for sensitized and remote operations

- providing new standards for digital messaging and interfacing to enable accessibility to data for all involved stakeholder in their pursuit for fine-grained situational awareness empowering decision-making processes

- boosting collaboration and data sharing throughout the global supply chain enabled by connected maritime transports (as in the cases of e.g. TradeLens and Global Shipping Business Network (GSBN)) and Internet of Things (IoT) (as in the case of e.g. Smart Containers)

Where we are now

Historically, both shipping companies and ports try to optimize their operations as much as they can, based upon a limited knowledge of what is happening now and comparing it with their pre-set plans. However, what is typical for the maritime sector is that many things do not turn out according to the initial plan, and changes are not well communicated to those that need to know. So, the involved actors then need to rely heavily on last-minute scheduling. Today, larger ports are establishing sophisticated capabilities for updating and re-assigning their resources at the last minute so as to reach as optimal service levels as possible. Waiting times have certainly been reduced, but the results remain sub-optimal.

The lack of predictability of transport events along the door-to-door logistic chain involving maritime means that clients are not receiving the service that they are coming to expect in other modes of transport. IoT initiatives associated with connected cargo, such as the smart containers initiative, seek to overcome this by providing supply chain stakeholder with data for monitoring the status and the progress of the transport. Connected cargo enables stakeholders to access data directly from the source regardless of whether the cargo is on a ship, in a yard, or at any other point during its pre-haul and post-haul journey.

Today, many ports of the world continue to operate on a first-come, first-served basis with the ship agent, acting on behalf of the shipping company, seeking to achieve the best possible port visit outcome for their client(s). In times gone by, port operators have acted somewhat in isolation and with limited information, often relying on glimpses on ship’s progress by following the AIS patterns of ships combined with trust in the ship agents’ reports on ship arrivals and desired services. Meanwhile, the ship operators and masters get only limited indications of the preparations being made from their ship agents. The increasing availability of digital information means that we are now beginning to see the establishment of information hubs as the foundation for data sharing among and between the communities of involved actors and as an interface to the outside world. One unresolved question is whether this refined landscape will challenge or enhance the role of the ship agent in the value-creation. What is important to be aware of is that the ship agent acts on behalf of individual shipping companies, most often associated to one type of trade, while the port is serving multiple shipping companies pursuing different types of trade.

Where we need to be

Some important initiatives and value foundations upon which to build are:

- virtual queue tickets combined with elastic time slot allocation enabled by shared situational awareness;

- collaborative concepts, such as the concept of port collaborative decision making (PortCDM) for enhanced coordination and synchronization of the port, as is occurring in other transport industries such as the aviation sector , enabling smart decisions to be based on collaborative alignment. A coordinated port is key to implementing virtual arrival and green steaming;

- expanding the scope beyond just-in-time arrival to also include a focus on just-in-time departures as well as taking into consideration the necessary horizontal integration, building upon the supply chain patterns of the goods flow as well as the visits made by transport carriers to different geographical areas;

- smartness in operations by moving from just being an information consumer to a digital service provider, such as in the concept of the smart port and smart ship;

- complementary data sources coming out of sensitized physical objects, such as the smart container initiative that offers the opportunity to be informed about the progress of shipments across modes of transport;

- industry driven communities for joining forces, such as the Digital Container Shipping Association and its initiatives for bringing competitors together to better respond to the opportunities of digitalisation, by acknowledging that digitalisation requires collaboration with others, even competitors;

- alignment between regulatory and voluntary information sharing communities , expanding the scope beyond peer-to-peer interaction;

- developing the practice of scheduling and contractual processes for carrier visits to ports as transhipment hubs; and

- expanding the concept of a port being a window to the sea to the port being an interface towards multiple modes of transport.

Final reflections

In order to overcome the current disconnectivity, we need to adopt a holistic approach to innovation and change. The discipline of maritime informatics , uniting practitioners and academics in a joint effort, has been established specifically to support this development by identifying, through analysis, how the maritime sector can be developed towards more profitable, resilient, predictable, and sustainable operations, empowered by digitalization.

Digitalization challenges the legacy of maritime operations by providing great opportunities to bring actors together that have never been collaborating before. Numerous initiatives on standardization and collaboration that enable enhanced connectivity are now coming forward, both from the regulatory point of view as well as on the business level.

Digitalization also challenges existing practices. Is it really enough to continue as usual, but just by electronic means, to balance capital productivity and energy efficiency that all involved parties need to jointly contribute to? Does this situation not both expect us all to come together and think of how new patterns of behavior should emerge which also challenges existing roles?

In this article we have highlighted some fundamentals of sea transport that come out of taking what happens at sea and at shore into account when introducing means for, and new practices, into play. At the core is to acknowledge the different perspectives of beneficial cargo owners provided with cost-efficient, visible, and predictable transport services in a sharing economy enabled by shipping lines and ports that are striving towards timely performance with high utilization of their infrastructure. The different digital data streams coming out of contemporary digitalization efforts along the supply chain should be used to redesign the processes and be the basis for the development of value-added services.

To echo another message by Professor Hammer “Think Big. Re-engineering triggers changes of many kinds, not just the business process itself. Job designs, organizational structures, management systems - anything associated with the process - must be re-fashioned in an integrated way. In other words, re-engineering is a tremendous effort that mandates change in many areas of the organization”.

There are great opportunities for the maritime sector. We must look beyond the single organization and move towards co-producing value for the clients of the maritime supply chain, such that everyone is a winner. Empowered by digitalization we hopefully will see the end of the era of sub-optimization.

About the authors

Mikael Lind is Associate Professor and Senior strategic research advisor at RISE, has initiated and headed several open innovation initiatives related to ICT for sustainable transport of people and goods. Lind is also the co-founder of Maritime Informatics, has a part-time employment at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, and serves as an expert for World Economic Forum, Europe’s Digital Transport Logistic Forum (DTLF), and UN/CEFACT.

Hanane Becha is the IoT program Project lead at DCSA and also the lead of UN/CEFACT Smart Container Project as well as the UN/CEFACT Cross Industry Supply Chain Track and Trace Project. Hanane has a solid background from the IoT provider perspective, having worked at TRAXENS for many years. Hanane has received a Ph.D. and an M.Sc. in Computer Sciences from the University of Ottawa, Canada.

Andre Simha is the Chief Digital & Information Officer at MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company, the second largest container carrier in the world, whose team is responsible for implementing and developing the complex data flow between the company’s headquarters and its agencies around the globe, as well as steering the business towards the digital future of the shipping and logistics sector. Simha is also the chairman of the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA).

Steen Erik Larsen is the head of Technology M&A in A.P. Moller – Maersk, the global integrator of container logistics, connecting and simplifying the supply chains. Larsen has the responsibility of the enterprise risk management aspects pertaining to information technology in integration and partnering, and is also representing Maersk in the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA).

Eyal Ben-Amram is the CIO of ZIM Integrated Shipping Services Ltd., one of the top ten container carriers in the world. Ben-Amram is responsible for all the operational systems, the Digital transformation and development of advanced systems/solutions and is also a member in the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA).

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

David Marchand is the CEO of Traxens. Traxens helps its customers gain full visibility throughout their supply chain, by providing digital services and advanced IoT technology. Traxens is committed to accelerate the digital transformation of the global container supply chain industry and promoting the standardization of protocols between all actors of the value chain.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.