Interview: Enric Sala on the Critical Role of Marine Protected Areas

[By Jessica Aldred and Jack Lo Lau]

Enric Sala is both a leading ocean explorer and a visionary. Originally an academic, he grew tired of “writing the obituary of ocean life”, and decided to start a new career finding ways to protect it. He approached National Geographic with an idea for a project that would “combine exploration, research and media to inspire governments to create marine reserves”. Appointed a National Geographic fellow, he launched his Pristine Seas initiative in 2008. Fifteen years on, the project has helped drive the creation of 23 marine protected areas (MPAs) covering more than 6 million square kilometers of ocean.

Enric Sala at the UN Ocean Conference in Portugal last year (Image: Regina Lam / China Dialogue Ocean)

Under the Pristine Seas banner, Sala has travelled the world examining all sorts of different ocean ecosystems. He has studied everything from microbes and algae to large marine mammals, and he’s reached places very few humans have been before. These experiences have shown him how important and beneficial it is to protect the world’s marine environments, and given him evidence to convince politicians that changes need to be made. And he is succeeding. He considers himself an optimist, and as he told China Dialogue Ocean, he even dreams of one day taking Chinese President Xi Jinping on an expedition to the bottom of the ocean.

We caught up with Sala in June at the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal, to talk about his expedition earlier in the year to the Pacific and Caribbean waters of Colombia.

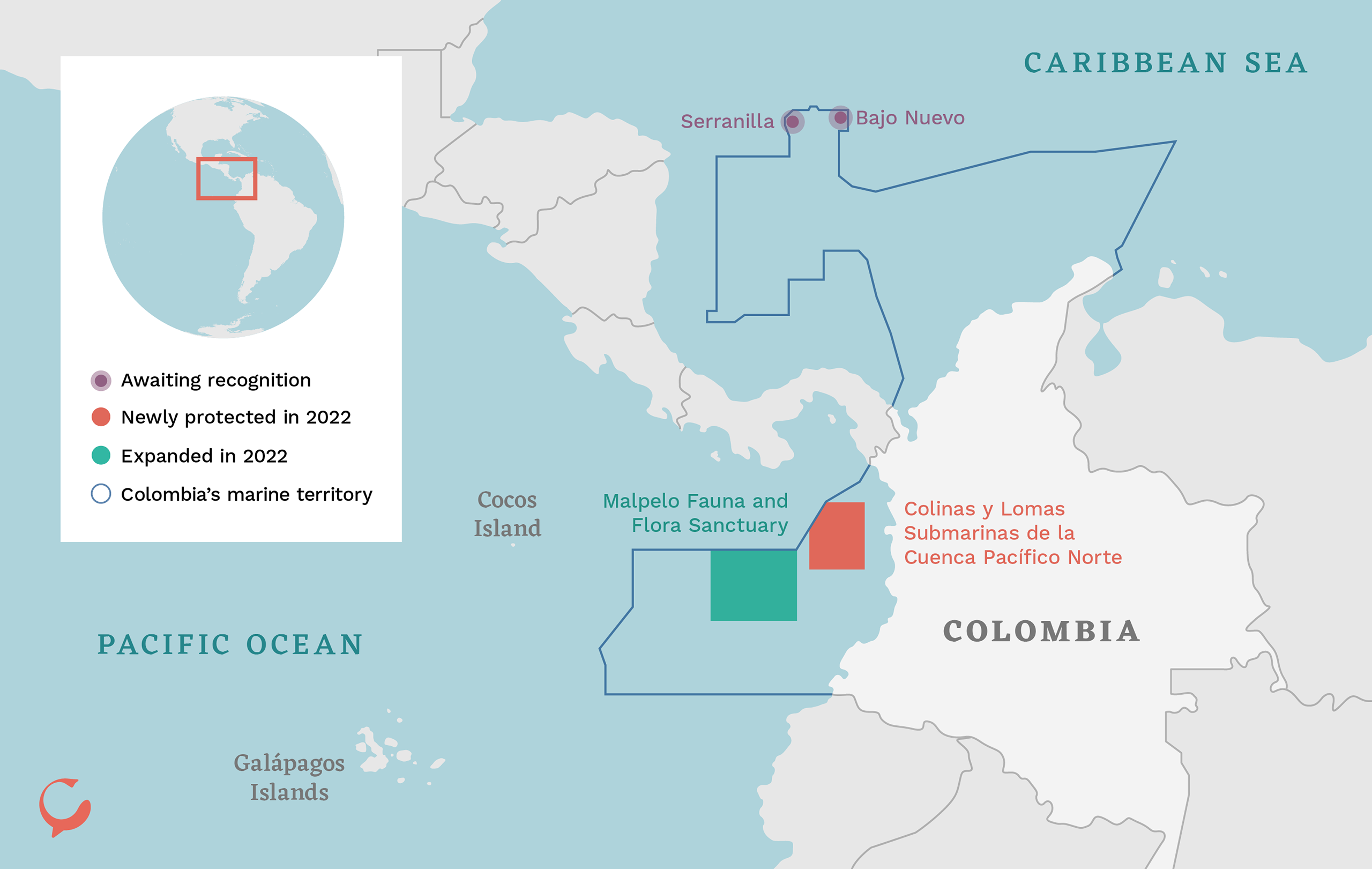

Note: The map only shows the protected areas mentioned in this article. The islands of Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo are currently administered by Colombia but in an area disputed by Nicaragua. (Data source: Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia; Graphic: Ed Harrison / China Dialogue Ocean)

Note: The map only shows the protected areas mentioned in this article. The islands of Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo are currently administered by Colombia but in an area disputed by Nicaragua. (Data source: Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia; Graphic: Ed Harrison / China Dialogue Ocean)

China Dialogue Ocean: Can you tell us about your expedition?

Enric Sala: We went to provide scientific research to inform the process of creating several MPAs that the Colombian government committed to as part of their plan to protect 30% of their waters – not by 2030, but before 2030. We’re talking eight years before the deadline. The expedition was fantastic, we were able to explore deep reefs with our submersible. We found an extraordinary abundance of deep-sea fish that were larger than anybody thought. Also, deep coral systems that had never been described before.

Why is this area important to study?

Colombia has this gem, Malpelo Island, which is protected as a large marine sanctuary. We were able to survey the areas around the sanctuary. Malpelo sits on top of an underwater ridge. It’s the only part of that ancient ridge that actually breaks the surface. We explored underwater seamounts, and we were able to demonstrate that not only Malpelo, but Malpelo Ridge – the entire chain of underwater mountains – is extremely important. Not only for the biodiversity that is there, but also for the endangered species that migrate between these protected islands: Malpelo in Colombia, Cocos Island in Costa Rica [and the] Galápagos Islands in Ecuador. And very often they follow these underwater ridges. We found incredible abundances of hammerhead sharks – on the surface, in the middle of nowhere, 200 metres over the top of seamounts. These are features that we cannot see from the surface, but animals can feel them, and they use them as a migratory highway, like stepping stones between islands.

Where does this highway go to and from?

There is not a single highway. When people talk about a [wildlife] corridor, there is not “a” corridor. Animals migrate throughout the entire eastern tropical Pacific, and different species have different migratory pathways. For example, hammerhead sharks have been tagged in the Galápagos, and they travel to Cocos Island, they travel to Malpelo, and then from there, the females travel to the coast to give birth in the mangroves. So the connectivity of these corridors is very complex and they not only link these oceanic islands, they also link with the coast. Different habitats are essential for different life stages of these species.

Did you use any new tools or techniques during your expedition?

We used Argo. It’s a diving live-aboard [vessel] for tourists based in Costa Rica. They have this wonderful machine, the DeepSee submersible that goes down to 450 metres. Also we have our drop cams, which are basically glass balls that we can drop over the side of the boat and explore as deep as 6,000 metres. Then we have our scuba [gear] and diving rebreathers and remote cameras, so we were able to explore everything from the surface to the deepest habitats.

What was the most amazing thing that you saw?

We saw many amazing things. When we retrieved one of the cameras that we had on the surface, we saw over 20 hammerhead sharks in one frame, in the middle of nowhere – we were 200 miles from the shore. We also saw groupers that were so large they were 40% larger than the maximum size ever reported in scientific literature. We saw deep coral reefs with an extraordinary abundance of fish that had never been described. And in the Caribbean, also, we saw some of the largest abundances of sharks, on an atoll, one of the most remote atolls in the Caribbean – Serranilla – in the northernmost part of Colombia’s waters. That place is protected, because there is a little navy garrison there, so nobody goes there to fish. So it’s not only one of the most remote places in the Caribbean, it is also one of the best preserved.

How will your discoveries be used now?

The scientific data that we collected has already been used by the Colombian government to designate protected areas around the underwater mountains that we visited. We are now producing a National Geographic film that is going to showcase Colombia’s ocean conservation leadership.

Will your findings change any of the policies or the management of these areas?

What we found helped to inform the expansion of the Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary. That’s a no-take area where fishing and other damaging activities are banned. And our data also informed the creation of two new no-take marine reserves around the two northernmost atolls in the Caribbean belonging to Colombia [Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo]. Plus, the creation of a new area, the Colinas y Lomas Submarinas – underwater mountains and hills – which is going to be a marine managed area, also on the Pacific coast.

What about other Latin American countries – what’s their record when it comes to protecting the ocean?

[Many] countries have a lot of work to do. For example, Peru apparently has 8% of its waters protected. But the area that’s truly protected from fishing, where there is no fishing or other extractive or destructive activities, is negligible. It’s much less than 1%. Peru happens to be a big fishing country, and its fishing industries oppose protections because they argue that this will harm them. This is a false argument. We have evidence from all over the world that when you create no-take zones, it allows species to recover and help repopulate the rest of the ocean. One example is Chile, which is also a big fishing country. It has protected 25% of its waters completely from fishing and other extractive activities. And now its fishing industry is very happy, because their catches are better. Marine reserves are not against fishing, they are an essential tool to allow fishing to continue in the future.

What other reasons are there to protect the ocean?

It’s very important that everyone understands that protecting the ocean is not just something that benefits fish and corals. We all depend on a healthy ocean. It gives us more than half of the oxygen we breathe, which is produced by marine bacteria and microscopic algae. Most people don’t know this. The ocean also helps to regulate the climate and capture some of the carbon pollution we put into the atmosphere. So we need a healthy ocean if we are to continue to thrive on this planet.

Science has a fundamental role to play in providing information, but science takes time. Do we have enough time to make the changes we need?

Science takes time, but we have enough science to make decisions now.

So why aren’t decisions being made?

Given all that we know, if decisions are not being made, it’s because of pressure from economic and industrial groups that have short-term interests and do not really care about long-term sustainability.

What can ordinary people do?

There are many things ordinary people can do to help solve environmental issues. One is to vote properly for politicians who have a programme that is in line with conservation needs. The choice of politicians decides public policy. So, electing the right candidate is the most important thing the ordinary citizen can do. The other thing they can do is to eat more plants and fewer animals. We consume too much meat, and livestock use a lot of resources, land and fresh water, and also produce huge amounts of methane. So reducing meat consumption would help combat climate change. Half of agricultural land is used to feed livestock, which is a huge inefficiency. To be able to restore that land, which is in many cases degraded, to recover the natural ecosystems that offer so many benefits to society, that would be ideal. Besides, eating more plants is good for your health.

At this conference there has been a lot of talk about deep-sea mining. What are your feelings about what has been said so far?

Deep-sea mining has the potential to cause an ecological disaster. We don’t have enough information about the ecosystems that would be affected by mining. And what would the climate change impacts be? We have seen that trawling, by disturbing sediments on the seabed, generates carbon dioxide emissions that are even greater than those from aviation globally. Deep-sea mining would disturb sediment on the seabed on a much larger scale, so it is very likely to generate carbon emissions that would contribute to and amplify global warming.

You were at the first ever UN Ocean Conference in 2017. How far have we come since then?

It’s been five years since the first UN Ocean Conference in New York. There is much more awareness about ocean issues. Back then, many – including conservation organisations – thought that the 30×30 target [to protect 30% of the planet by 2030] was too ambitious. Now we have over 100 countries supporting it. So that’s progress. We have more countries that have created significant marine reserves where marine life thrives.

But on aggregate, the ocean is in worse shape than it was in 2017. There’s been more fishing: today more than three-quarters of our fish stocks are exploited to the limit or over-exploited. Plastic pollution has grown dramatically. Dead zones continue to increase. Invasive species continue to invade ecosystems, destroying the natural balance and also creating huge economic losses. We have more extreme weather events because of global warming, which is also raising the sea level and destroying coastal habitats and infrastructure. So we are in worse shape, even though we’ve had some progress.

The good news, and this is what I’m optimistic about, is that we know that when we give space to the ocean, the ocean comes back spectacularly. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. We see it in these marine reserves that have been created by local communities, Indigenous peoples and governments. And we know what we have to do, we just have to replicate this on scale.

How optimistic can we be about conferences like this one?

The problem with these conferences is that much of the time is spent repeating the obvious: that the ocean is vital to our lives, that we are degrading the ocean, that it is important that we do something, that such-and-such a country is committed to policies to conserve the ocean. Things we’ve heard for 20 years. People who come here to repeat the same thing are wasting their time; they’re wasting everyone’s time.

But I am optimistic because there have been extraordinary announcements at this conference. There has been action beyond empty words. For example, the government of Colombia has designated new MPAs that bring its protected waters to 30%. And they have achieved this eight years from 2030, which was the proposed target. If they have done it, more countries can do it. I wish more countries had come to Lisbon to announce similar things. But the fact that both Colombia this year and Costa Rica last year have met this goal gives me hope that other countries can achieve it.

Jessica Aldred is special projects editor for China Dialogue, focusing on globally important environment themes including the oceans, palm oil and biodiversity. She spent 10 years as deputy environment editor at the Guardian, and has nearly 20 years’ experience working in the newsrooms of major media organisations in London, Sydney and Melbourne.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Jack Lo Lau is Latin America editor for Diálogo Chino (Andean Region), based in Lima.

This article appears courtesy of China Dialogue Ocean and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.