How Tide Predictions Made D-Day Possible

D-Day, codenamed Operation Neptune, was the largest amphibious landing not only in World War II, but in history. It marked the start of the liberation of German-occupied France (and later western Europe) and laid the foundations of the Allied victory on the Western Front.

But what most people don't know is that ocean tides played a key role in this historic day. In this interview - transcribed and adapted from an edition of NOAA's Ocean Podcast series - NOAA managing editor Troy Kitch spoke with Greg Dusek, a physical oceanographer and senior scientist at the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, about the critical role that tide predictions played in the landings.

Kitch: D-Day, codenamed Operation Neptune, was a massive, complex amphibious landing along the Normandy coast of France that began on June 6, 1944. Within ten days there were half a million troops ashore, and within three weeks there were two million. All told, D-Day laid the foundations of the Allied victory on the Western Front. But most people don’t know how ocean tides played a crucial role in the initial phase of the invasion. Joining us is Greg Dusek, a physical oceanographer and senior scientist at the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, the tides and currents office of the National Ocean Service. Greg, what sort of conditions were the allies looking for as they planned the invasion of Normandy?

Dusek: So the allies were planning an amphibious assault. They were going to cross the English Channel to the French coastline, near Normandy. Because they were going over the ocean, they needed good weather, so they needed to find a time where the waves were going to be minimal and the winds were going to be minimal, and obviously that’s something they really can’t plan ahead of time. But they knew that, in the summer months, you were more likely to have good weather, so they wanted to plan a time in the summer for the assault.

They also wanted to have a time period where you had a full moon or close to a full moon the night before the assault, and the reason for that was, they were going to have airborne infantry sent behind enemy lines the night before, and to do that, you needed some sort of lights for them to be able to figure out where they’re going. So they wanted close to a full moon the night before.

And then, lastly, they were looking for a time with low tide shortly after dawn. And the reason they needed it shortly after dawn, was because they needed a couple hours of time for the amphibious assault groups to travel across the English Channel in darkness, but then enable the naval bombardment to have daylight to be able to target initial areas of interest to bombard, before the amphibious assault began. Those criteria, you know, didn’t have a lot of times to work with, and June 5th, 6th, and 7th of 1944 were the three days that were identified.

Kitch: That is a lot of environmental factors to have all fall into place. That last part, looking for a time with low tide shortly after dawn, is where we get to the science of predicting the tide for a particular location.

Dusek: So tide predictions were top secret during WWII, and the reason for that was you wanted to limit the axis information about allied-held coasts, you didn’t want to divulge any information that they might not already have about the tide or our own coastlines, so they couldn’t plan their own attacks.

And then the other important part was that, if we were generating predictions for positions we were likely to attack, if the enemy found those predictions, it might tip them off as to where we were thinking about attacking next. So all of the work done relating to tide predictions was really secretive and it was a lot of work to make sure that none of that information escaped and was available to the enemy.

Kitch: And this was of course well before computers. Can you tell us a bit about the basics of what tides are and how people predicted tides in the past, leading up to WWII?

Dusek: Tide predictions enable us to tell when is high and low tide and what time is high and low tide going to occur at different coastal locations. The tide is related to the position of the sun and the moon relative to the Earth, and so going back even to the mid-1700s, people understood that when you had high tide every day, and how high the tide was, relates to, in particular, the phase of the moon. And so, even in the mid-1700s in colonial America there were tide predictions of the timing of the tides at various harbors. They weren’t terribly accurate, but they did provide some information which would be useful to mariners and to citizens.

But it wasn’t really until the late 1800s that a few folks — Sir William Thompson, who later became known as Lord Kelvin in England, and William Farrell of the U.S., who was at the U.S. Coast Survey - they were the first ones to figure out if we go and collect the observations, go measure the water level for a month at a time at a certain location, you could then figure out what frequencies make up the tide, what are known as tidal constituents. And if you knew those tidal constituents at a particular location, then you could use that information to generate tide predictions, or very specific water levels and times of the tide at a certain location even months or years into the future.

Kitch: So how were tide predictions calculated once this was figured out in the late 1800s?

Dusek: Understanding that there were these specific frequencies that related to the tides, these tidal constituents, you could recreate those mechanically. So you could have these different gears and pulleys represent specific frequencies and then use what’s known as a tide machine to, basically, you put in those constituents, and that tide machine would spit out a tidal curve telling you exactly the times and water levels associated with certain tidal constituents.

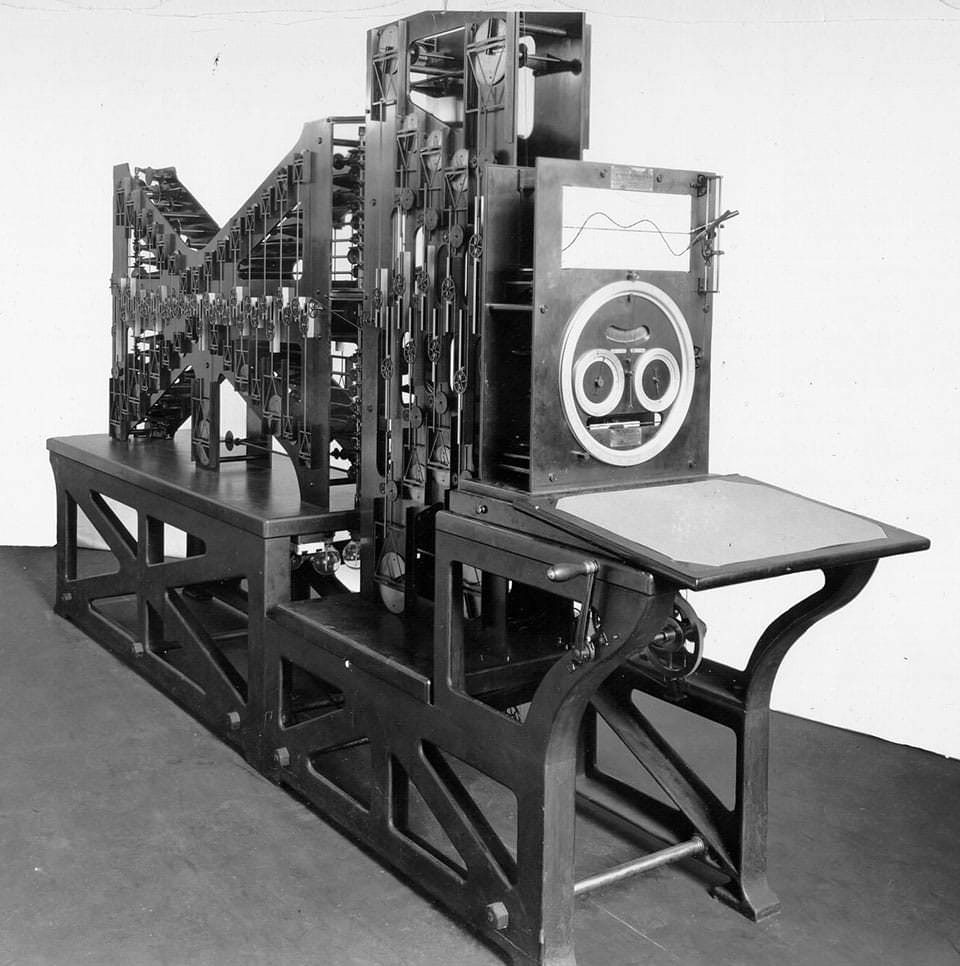

Some of the first tide machines were created in the late 1800s, and in the U.S., the best tide machine that was really ever created was finished in about 1912. If you ever visit NOAA, you can find it right in one of our buildings. We still have it there today. It was called ‘old brass brains,’ and it was this metal machine about eleven feet long, about as tall as a person, and people would operate that all the time, generating tide predictions from tidal constituents — and you can generate those predictions for anywhere in the world, as long as you had the information about the constituents.

The U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey used tide prediction machine No. 2, fondly referred to as Old Brass Brains, to predict tides from 1912-1965. It was the first machine made to simultaneously compute the height of the tide and the times of high and low waters. (NOAA)

And the big thing with this machine is that this used to be a process that was done by hand. There was a quote in a New York Times article when the machine was first put out, where they say, ‘the machine turns out in ten to 15 hours the work that would keep a mere human calculator busy for six months.’ So, you know, we used to have human calculators, and it would take about six months for them to do one set of tide predictions, and now we could do it in maybe a day or so.”

Kitch: I’m still not clear on the idea of tidal constituents.

Dusek: So tidal constituents are specific frequencies that represent the position of the moon and the sun relative to the Earth, and how that influences water level. You can calculate the tide with not too many tidal constituents, maybe 20 or 30. The tide machines of the time could solve for about 37 tide constituents, which is usually more than enough to get a really accurate prediction, but there are several hundred known constituents that we can solve for today if needed.

Kitch: How many of these mechanical tide machines did the Allies have during the war?

Dusek: There were a number of these tide machines by the time WWII rolled around. We had one in the United States, there were two in the United Kingdom. Pretty much every maritime nation at that point had some sort of tide machine to enable them to generate tide predictions. But because we only had three primary machines within the allied nations, it was really important to keep them safe.

So in the UK, for instance, they had these two machines which they had in two different locations, because they were really afraid of the Germans figuring out where the machines were and then firebombing them to destroy them, because they would’ve been high value targets. So the location was a closely held secret and the really tried to keep them hidden. If they lost both of them, that could be a huge implication on the war effort, so it was really important to keep the machines safe.

Kitch: And this leads us back to planning for the D-Day invasion. What were some of the challenges of predicting the tides along the Normandy coast where the Allies planned to land?

Dusek: So the tide range around the Normandy beaches was around 20 feet, and because you have this really large tidal range, the beach you’re going to have to traverse is going to be wildly different depending on if you’re at low tide or high tide. At low tide, you might have 2-300 yards more of beach to cover during an amphibious assault than at high tide. So because of that, you really want to minimize your exposure. The other important part about the tide range is that the water level is changing very rapidly. So you could be gaining or losing about a foot of water every 15 minutes.

On top of that, the Normandy coastline is kind of complex, and that influences the tides fairly substantially as you go along the coast. So, the allies had five locations they wanted to land at. Utah and Sword were the two furthest apart, about 100 kilometers apart, and the tide could vary by more than hour between those two locations, and so knowing the precise time of low tide was going to be really important.

Kitch: So how did the Allies get the information they needed to do their calculations for these extreme tide conditions?

Dusek: At this time in history, there was tidal information at lots of the major coastal cities. There were tide constituents generated from water level observations at nearby cities — Cherbourg to the West and Le Have to the East — but now both of these locations were about 100 kilometers away from the landing beaches, and so the predictions that you generated at those locations would probably not be very accurate for where the landings were going to occur.

And so they had, in the tide tables at the time, there was some information closer to the landing zones, but it wasn’t nearly as detailed and there was even a note in the tide tables that said, ‘these predictions may not be accurate.’ So they really didn’t have much to go on for the exact landing locations. Apparently, the allies actually sent in some special forces, night reconnaissance, ahead of the attack, to look at the bathymetry (the shape of the bottom), the type of sand that was there, and to even collect a little bit of information about the tides, which could then support calculating new predictions for those specific landing zones.

Kitch: And why was it so important to stage the invasion at low tide?

Dusek: They knew they wanted to land at low tide, so that they could send their initial forces to clear out the number of objects on the beach, but if you can imagine that they got tides just a little bit wrong, say they were off by 30 minutes, 45 minutes, and they landed just before low tide. Well, because of the tide range, water’s dropping about a foot every hour right before low tide, and so your amphibious craft would’ve arrived, unloaded the troops, the tides would’ve dropped, and all the craft would’ve been stuck on the beach — and then, you know, you’d be gumming up the whole operation, you wouldn’t be able to have reinforcements come in, and it would have been a disaster. And so they needed to arrive just after low tide, so that water levels are rising about a foot an hour, and it would enable their crafts to drop the troops and then get back out of the way for the next round of troops to arrive.

Kitch: At the time, German forces knew that the allies would likely try an invasion of the French coast from across the English Channel. Can you talk about how the Germans were planning for this?

Dusek: The Germans and Gen. Rommel were really expecting the allies to attack at high tide, because at low tide there would be maybe 2-300 yards of beach that the amphibious forces would have to traverse, leaving them exposed for an extended period of time. Because of that, Rommel had all of these obstacles placed along the beach — millions of obstacles along the French and Belgian coastlines — and so, they were convinced that an attack would happen at high tide. Now, the allies saw these obstacles and decided that a high tide attack wouldn’t be possible, and instead they would have to plan their attack at low tide, giving their initial troops a chance to move obstacles out of the way, blow up obstacles, and clear a path for the heavy infantry and tanks and things like that, that would follow the initial attack.

Kitch: So you said that all the conditions that needed to fall in place — the moon, the weather, the tides — meant that the small window between the 5th and 7th of June were the best dates for the Allies to launch the invasion. How did the Allies settle on June 6th to commence operations?

Dusek: On June 4th, the weather was going to be too bad, so they didn’t attack. They waited until June 6th. The weather was still not great and it was very questionable, but Eisenhower made the decision to attack because he was worried that, if it failed here, they’d have to wait at least two weeks and maybe a month or more to go forward with the assault, and then it could’ve been figured out. They didn’t want to wait that long, because they were losing lives like crazy.

Even though the weather was rough getting across the Channel, it actually worked in our favor because Rommel — because the weather wasn’t any good and because it was low tide at first light and he was anticipating a high-tide assault — he was actually not even in Berlin, he was visiting his wife for her birthday somewhere else, and so wasn't prepared even for the assault at all. So we actually caught them off guard by choosing to attack that day.

Kitch: Well the invasion of course succeeded, so among all of the factors that led to this success, I guess that means that the Allies got the tide predictions right for the Normandy coast on June 6th, 1944?

Dusek: Later on, people went back and using computers and using hydrodynamic models re-ran a simulation to look at how accurate the predictions were around the Normandy coastline for the assault and found them to be really quite accurate, you know, using a mechanical machine and data collected from a few hours in a midget submarine or something, was almost as accurate as we can determine today.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

I would say anecdotally in our office, we’ve looked at a lot of historical predictions going back to the late 1800s, early 1900s, and compared them to what we can find today with modern instruments and modern computers and are always amazed at just how accurate, you know, what people were able to figure out with really minimal amounts of information and technology, and could get pretty darned close to what we can measure today with all of the technology we have.

This interview appears courtesy of NOAA's National Ocean Service and is reproduced here in an abbreviated form. The original - including the podcast audio - may be found here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.