Encrypting Vessel ID Data Can Thwart Maritime Piracy

The regulations the International Maritime Organization (IMO) issued in the wake of 9/11 regarding ship location and identification reporting have made it easier to track vessels–but not only for the good guys. Since the monitoring and reporting information is broadcast on open channels, anyone can listen in, including pirates and cyber attackers.

While the overall number of piracy incidents decreased in 2022, even a smaller number of attacks can be highly dangerous. In fact, 96 percent of the attacks that happened in the first half of the year included vessels being boarded, with more than 20 crew members taken hostage. Meanwhile, cybersecurity attacks on ships continue to rise.

Encrypting vessel ID, location data streams, and other information is an effective way to mitigate these threats. By encrypting the data and making it accessible only to authorized officials, ships can securely transmit information pertaining to their locations, identities, cargo, and more. This information can therefore be kept from potential attackers, allowing ships, crew, and cargo to navigate risky waters safely without having to turn off their tracking devices.

A difficult choice: send information, or turn off transmissions?

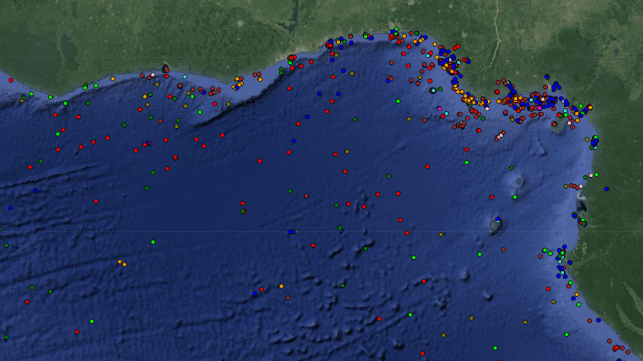

Many vessels use Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) to transmit information pertaining to their identities, headings, speed, and various other characteristics. Usually, these transmissions happen every few minutes.

AIS is great for traffic routing, collision avoidance and to continually keep tabs on vessels, but since these communications are transmitted over open frequencies the transmissions themselves can effectively serve as homing beacons for pirates. Often, this results in crewmembers turning off tracking devices and transmissions to keep their ship’s location and identity a secret. For example, if a ship is transiting a high piracy area like Southeast Asia, or traversing a war-torn location like the Black Sea, the crew may turn off the vessel’s AIS until the ship reaches safer waters.

Unfortunately, this practice goes against the International Maritime Organization (IMO) Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) requirements and poses its own risks. If the ship in question becomes incapacitated or distressed, no one will know where it is or how to get to it.

This begs the questions: Is it better to turn off transmissions to protect against possible piracy? Or is it safer to continue to send identity and location data, which might invite the type of incident that AIS is meant to avoid?

Securing the data itself eliminates the need to choose

It does not have to be a binary choice. Vessels can continue to transmit critical information and make that information available to those who need it while still protecting their locations and identities. This can be done by securing the actual data that is sent to shore, rather than just securing the communications method used to transmit the data.

In this case, a protective “wrapper” is placed around the sensitive payload being transmitted. That wrapper encrypts the data, making it impossible for unauthorized users to view, access, or use it. All information being transmitted can be encrypted, or only some of it. For example, if a ship’s message payload is 16 lines, and half of those lines contain sensitive identity and location information, that portion of the message can be encrypted.

Plus, objects can be tagged so they’re only accessible to certain users. For instance, a piece of code tagged “#release only to Coast Guard J2 intelligence function”, or "#release only to EU NAVFOR” will only be readable by users in that position. The same can be done for ship captains, local maritime authorities, and more. This ensures that only the personnel who need the information can get the information while keeping bad actors out.

This approach is based on an existing technology called the Trusted Data Format (TDF). The TDF is an open standard that is used to protect all manner of data, from emails to files and more. It has been used in the federal government for decades, and can now be applied to secure ship-to-shore transmissions.

Not just for location and identification data

Encryption does not need to be relegated only to location and identification data. Vessels transmit proprietary and highly sensitive information for regulatory and SOLAS purposes. For instance, information pertaining to hazardous cargo, such as munitions or biological materials, must be transmitted back to shore. Crews are also often required to broadcast data about the people on board their vessels, particularly if those individuals are emigrating from other countries.

All of this information can be easily encrypted, not only ensuring the safety of ships and crew but also supporting supply chain resiliency. Ships can broadcast specific cargo details without needing to worry about piracy or hacking threats. This allows cargo recipients to better understand what’s coming into port and when, so they can plan accordingly.

A better option for data protection

It is incumbent upon vessels operating under the flag of the United States and other global maritime authorities to safeguard the information vessels transmit to better protect crew and cargo. Until recently, the only truly effective way to do this was to turn off transmissions and hope for the best.

Encrypting data is a much better option. By placing a security wrapper around the data, crews can leave their communications open and remain secure in the knowledge that their information is being protected, regardless of how it’s transmitted.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Shannon Vaughn is General Manager of Virtru Federal. He leads the business development, operations, and delivery of Virtru’s federal engagements. Shannon brings 15-plus years of federal contracting experience to Virtru. He is also a career U.S. Army officer, currently serving at Army Futures Command in the Reserves.

Ben Minichino is President of Pole Star Defense, and he has 25 years of business development experience in defense and aerospace technologies. He launched Pole Star’s US Defense subsidiary office in St Petersburg, Florida with a highly specialized mission in support of the US Coast Guard, targeting US SOCOM and DOD customers.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.