Developments in Ship Recycling in 2019

For the sixth year running I have been asked by The Maritime Executive to provide a review of the year’s notable developments on ship recycling and my expectations for the coming year. I have to acknowledge at the outset that, by nature, this must be a subjective exercise, based on my own vision of what is the definition of responsible ship recycling and what should an acceptable recycling yard look like. It is therefore relevant to disclose that for some time I have held an unchanging conviction that the only way possible for ship recycling yards across the globe to satisfy and maintain common minimum safety and environmental protection standards is through the entry into force of the IMO’s Hong Kong Convention.

For me, this is the filter that defines what helps and what hinders progress towards ship recycling becoming a responsible international industry.

The Hong Kong Convention

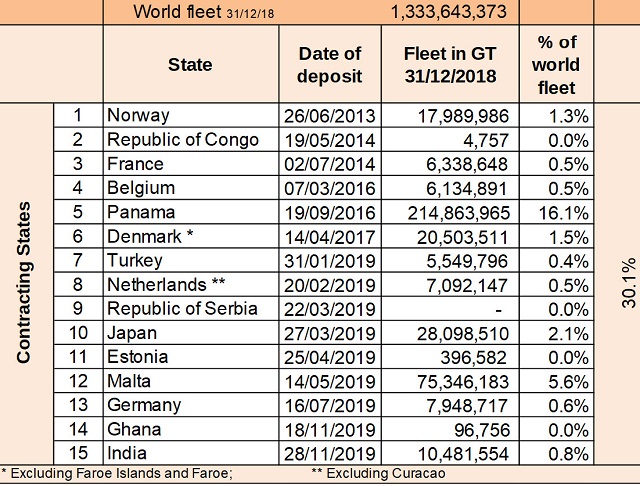

Although 2019 was the 10th anniversary of the Convention’s adoption in Hong Kong, by the beginning of the year only six countries had ratified it. (Note that a country wishing to become a Contracting State to an international convention can do this by accession to the convention or by a two-stage process that involves first signing the intent to become Party and then ratifying its signature. In this article the term ratification is used to mean either method.) Thereafter nine more countries ratified the Convention, as shown in the following table:

The ratification by Turkey was an important milestone, this being the first main ship recycling country to become a Contracting State of Hong Kong Convention. Note that in 2018 the four main ship recycling countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Turkey) recycled 96 percent of all tonnage, and that with the import ban of ships for recycling in China from December 31, 2018 this market share is expected to rise from 2019 to 98 percent.

Japan’s ratification in March was another milestone, partly because of the large tonnage that flies its flag, but also because of the great support that country has given, first to the development of the Convention, then to the voluntary implementation of the Convention to its ships, and last but not least to the support and aid it has already provided for the upgrading of recycling yards in India. Malta’s ratification in May was noteworthy because of its large fleet, which also is the largest in European Union.

All ratifications of the Convention are important and carry weight, but none as much as the ratification by India which took place near the end of the year. India happens to be the country with the largest “maximum annual recycling volume”, this being the measurement of recycling capacity that is defined in Hong Kong Convention (as the GT tonnage recycled in the year with the largest output, taken out of the preceding 10 years). According to this definition India has 31 percent of the world’s capacity based on its recycling of 12.2 million GT of ships in 2012.

However, the importance of India’s ratification does not stem only from its large capacity, but also from marking the anniversary date of Hong Kong Convention becoming the accepted standard for the ship recycling industry. The plain reality is that the international community decided to develop the Convention at the IMO to address the low safety and environmental standards that existed in the dominant recycling countries of South Asia, and not necessarily to address the standards that existed at the time in Turkey and China. The transformation that has taken place in most of the ship recycling yards of India in the last four years demonstrates the acceptance of the Convention as the mainstream industry’s working standard.

At the end of 2019 we face for the first time the real prospect of the Convention’s entry into force in the proximate future. The provisions for entry into force are: 24 months after the following three conditions are met: (1) ratification by at least 15 countries; (2) whose fleets together add-up to at least 40 percent of the world’s fleet; and (3) whose ship recycling capacities together add-up to at least three percent of their fleets. The first condition has already been met, while the second and third conditions are 75 percent and 87 percent satisfied, respectively.

To fully satisfy the second condition is quite straight forward as a ratification either by Liberia (currently 11.6 percent of the world’s fleet), or Marshall Islands (11.3 percent of the world’s fleet) is enough to meet the 40 percent requirement. However, on a point of detail, one needs to remember that the gross tonnage of the world fleet is presently increasing, with an annual rate of around 3.5 percent. Consequently, in subsequent years the market share of countries may vary from the figures quoted here, which relate to fleets at the end of 2018.

To satisfy the third condition, presently additional recycling capacity of 2.1 million GT is needed. This can only be provided by Bangladesh (present capacity 9.9 million GT), or Pakistan (5.7 million GT), or by China (8.2 million GT). The rest of the world (excepting Turkey and India who have already ratified) can only contribute 0.6 million GT altogether. Therefore, without one of these three countries the Convention cannot enter into force (unless a Diplomatic Conference was convened to agree different entry into force criteria through a Protocol– a very unlikely proposition).

Of course, as the world fleet increases the required capacity to satisfy the third condition will also increase from the 2.1 million GT mentioned above. Nevertheless, the conclusion remains unchanged, that the Convention cannot enter into force without the ratification by one more ship recycling country.

Interestingly, China will continue to have for a few more years significant “notional” ship recycling capacity arising from the tonnages it recycled before banning the import of end-of-life ships. This legacy capacity will stand at 8.2 million GT until April 2023 (which was the volume recycled in 2012), will then decline to 7.1 million GT until April 2024, to 5.0 million GT till April 2025, etc., until a decade has passed from the time the country stopped recycling foreign ships.

Therefore, noting that the Chinese fleet is currently 4.1 percent of the world’s fleet, and the fleet flying the flag of Hong Kong is 9.3 percent of the world’s fleet, it follows that if China with Hong Kong were to ratify the Convention today, then the three conditions will have been satisfied and the Convention would enter into force in just 24 months’ time.

Whereas it is tempting to hope that China will soon trigger the entry into force of the Convention using its notional ship recycling capacity, it must nevertheless be preferable to invite ratifications by countries with real ship recycling capacity. The eventual target must be for the ratification by both Bangladesh and Pakistan, which will cement the Convention as a truly global regulatory instrument, leaving no recycling capacity outside its reach.

In the meantime, it is likely that Bangladesh will be the first of the two countries to ratify the Convention. This is because the country’s administration is well aware of what is required to enable its industry to comply with the requirements of the Convention, thanks to a project funded by Norway and run by the IMO. Also, a leading recycling yard in Bangladesh has already transformed itself into a model industrial facility, becoming the first yard in the country to be awarded a Statement of Compliance (SoC) to Hong Kong Convention by an IACS classification society. A second yard in Bangladesh is expected to be awarded a Statement of Compliance soon, and it is understood that a few more yards are working towards compliance.

The Ministry of Industries of Bangladesh has declared its intention to ratify the Convention by 2023. If China does not ratify the Convention before then, a delay to 2023 to satisfy the entry into force conditions appears to be a very long wait. It is therefore hoped that the government of Bangladesh may be aided by a developed country or countries in order to establish the necessary infrastructure and systems in a shorter time scale.

Pakistan on the other hand does not yet appear to have made progress towards compliance with the Convention. Furthermore, in 2019 the country’s ship recycling industry suffered from adverse taxation; adverse exchange rates; and the cheap imports of billets from Iran, and consequently it has recycled very little tonnage.

The European Regulation on Ship Recycling (EU SRR)

From the beginning of 2019 the EU SRR mandates that European flagged ships must be recycled only in yards that are entered in the European List of approved yards. The 4th List of approved yards was published in December 2018 containing 23 yards based in the EU, two yards based in Turkey and one yard based in the U.S. In June 2019 the Commission updated its previous List by publishing its fifth List, containing 30 yards based in the EU, three yards based in Turkey and one yard based in the U.S.

The sixth European List of approved recycling facilities, which is expected to be published soon, will include a further four EU-based yards (in Lithuania, Latvia, the Netherlands and Norway) and a further three Turkish yards.

An EU List of approved yards that mostly comprise of EU-based recycling yards (incidentally, a number of which do not recycle ships) does not make sense, as the EU is the world’s largest net exporter of scrap steel, with the vast majority of its exports going to Turkey, Egypt, India, China and Pakistan. Obviously, it is not economically sustainable to be recycling large ships in Europe to produce scrap that will have to be transported to countries that already recycle ships.

The official data that are used by the IMO show that the EU’s combined maximum annual recycling volume (including Norway and the UK) is only 0.57 percent of the world’s capacity, while in 2018 the total tonnage recycled in the EU was 82,067 GT, representing just 0.45 percent of all tonnage recycled in the world (equivalent to a little more than two Panamax vessels).

As expected and foretold, in the first year of EU SRR’s application, only a handful of ocean-going ships were recycled in accordance with the Regulation. It must be concluded that many end-of-life EU flagged ships must have changed flag in 2019. It should be evident to all that EU SRR will fail in its enforcement unless its List includes a not-insignificant number of South Asian yards. It may therefore be logical to predict that within 2020 the first Indian yards may be approved and enter the European List.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

One other important development that will take place in the next 12 months is the provision of Inventories of Hazardous Materials (IHMs) to all ships over 500GT that intend to call EU ports after the December 31, 2020.

Dr. Nikos Mikelis is Non-Executive Director of cash buyer GMS.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.