Complex Russian Price Cap Makes Maritime Visibility a Must

Many commentators and analysts are speculating about the potential impact the Russian seaborne oil price cap will have on organizations and entities throughout the maritime ecosystem. With the December 5, 2022 deadline now upon us, the truth is that no one really knows. There are too many variables and unanswered questions.

Will Russia and Russian vessels cooperate with the price cap, or actively try to subvert it? And if an entity in India receives crude oil from Russia and a U.S. entity is interested in purchasing that oil, does the U.S. entity need to ask the Indian entity if the oil was price capped? Also, who is going to enforce adherence to the regulators’ set price?

These are just three examples of open issues. The way forward will depend on the resolution of the many unanswered questions that currently exist, as well as organizations’ respective appetites for risk. But one thing is clear: to even have a chance at compliance, organizations must be proactive in executing due diligence and detecting related deceptive shipping practices (DSPs).

Background and challenges

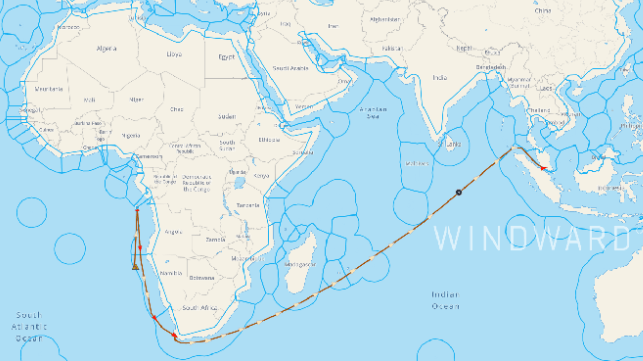

Russian forces invaded Ukraine in a full-scale assault that started on February 24 and created global shock waves. Economic sanctions had already been imposed days prior to the invasion and have since escalated.

Image 1: Timeline of sanctions imposed on Russian exports and oil since the beginning of the war

Image 1: Timeline of sanctions imposed on Russian exports and oil since the beginning of the war

A new set of extended regulations by the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI), the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), and the European Union (EU) will come into effect on December 5, 2022. These bodies established an embargo and a limiting price cap on all Russian seaborne oil trade. The new ban is designed to accomplish two goals that will likely be difficult to coordinate and reconcile: ensure the continued flow of Russian oil into the global market so as not to worsen the precarious global economic situation, while maintaining pressure on Russia by limiting the price for the supply and delivery of the oil.

While only traders and importers have direct access to the price of the transactions, the restrictions and price cap apply to all shipping stakeholders across the supply chain, including financial institutions, shipping companies, and insurance brokers. This creates a challenging dependency on counterparties to obtain sufficient evidence for the legitimacy of the deal.

Apart from the dependency on others for price proof, shipping stakeholders now face other challenges following the December 5 go-live date.

According to Vortexa, a company providing real-time information and analytics for crude oil and refined oil product flows, one of these challenges is that Russia will require more than 200 tankers to export its oil to the four countries that will still be able to accept it – China, India, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Turkey.

It remains to be seen whether there will be a two-tiered fleet:

1. Western/global; 2. Dark Fleet

Or a three-tiered fleet:

1. Western; 2. Dark fleet; 3. Those who maintain ambiguity.

The third category has been prevalent in Venezuela trade, with a few Greek vessels sanctioned in 2020 by the Trump administration.

The four legitimate destinations mentioned above are further away than Europe, meaning that there likely will not be enough available oil tankers to extract the oil from Russia and complete the lengthy voyages. During the winter, more ice vessels will be needed, too.

This may cause freight and oil rates to rise, and the effort to extract all the needed oil from Russia will inevitably lead to more ship-to-ship (STS) operations that will occur in known and new hot spots.

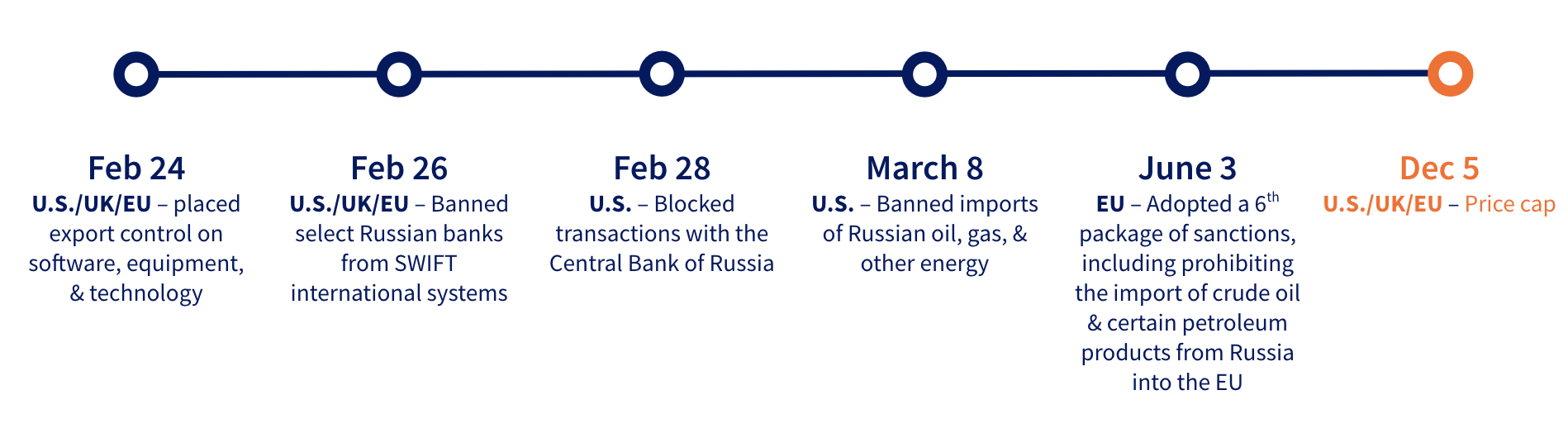

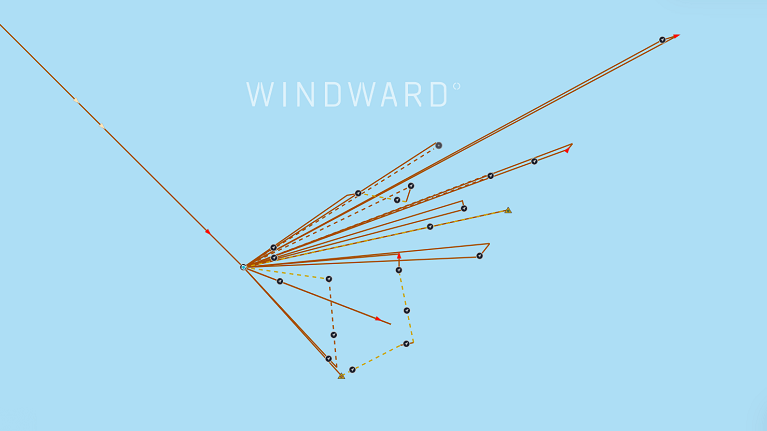

While STS operations can be completely legitimate in the maritime industry, a sharp increase in the number of such meetings in specific areas opens a window for illicit actors to conceal illegal activities. Windward’s insights show that while seasonality trends of the global STS operations between Russian-affiliated tankers remained the same when comparing 2020-2021 to 2021-2022, the volume of such operations dramatically increased since the beginning of the war.

Image 2: A rise in STS volume in 2021-2022

Image 2: A rise in STS volume in 2021-2022

STS operations are not the only thing stakeholders need to be aware of with the implementation of the price cap. In addition to the price attestation, companies must optimize their due diligence processes to check for any ownership changes; determine who is the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO); and detect dark activity, GNSS manipulations, first-time visits, and voyage anomalies.

These can be directly related to the much-discussed shadow fleet (vessels that officially do not exist) that poses a real risk to organizations. Orgs cannot do much about the shadow fleet, since the vessels’ lack of registration makes tracking extremely difficult and an obstacle to full compliance. By monitoring the above behaviors, users can track their counterparties and the vessels they are meeting with to identify any suspicious draft changes and flag vessels trying to hide in plain sight.

Even if there is a price attestation in place and everything is seemingly above board and legal, actionable insights and real-time alerts for such high-risk behaviors are valuable, and can prevent reputational/financial risk by enabling visibility:

- Beyond the price of the trade

- Into the organizations involved in potential transactions

- Into the origin of the oil being shipped/financed/insured

First Russia-related GNSS manipulation shows price cap’s complexity

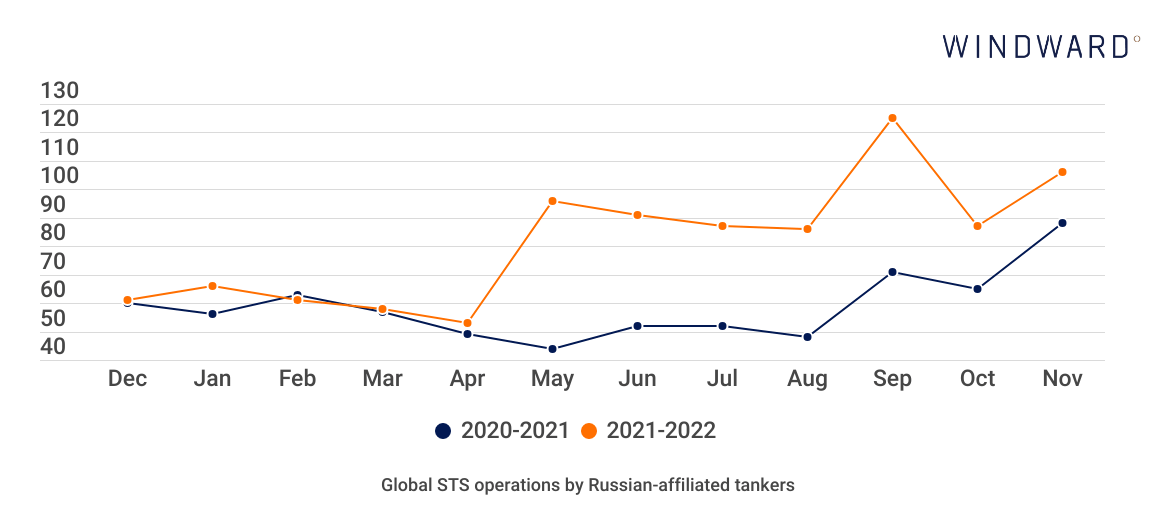

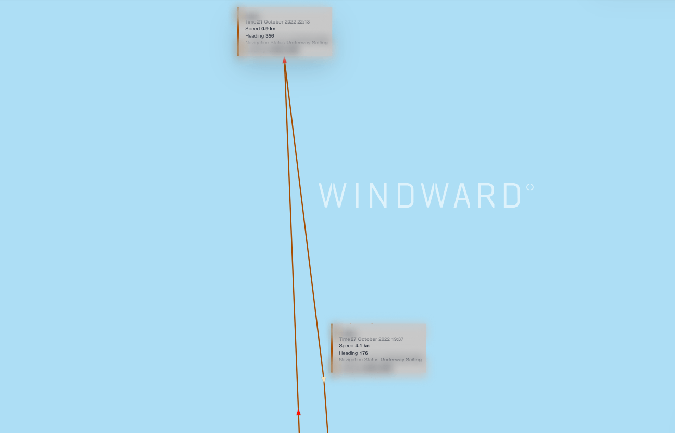

One recent example of hiding in plain sight and the complexity of determining who may be carrying Russian crude oil is a crude oil tanker sailing under the Cameroon flag. When looking at the operational history of this vessel, there is seemingly nothing illegal about its behavior, and no Russia connection.

Image 3: Vessel profile of the crude oil tanker, showing it has been high risk since July 2022, following its first GNSS event

Image 3: Vessel profile of the crude oil tanker, showing it has been high risk since July 2022, following its first GNSS event

In September of 2022, according to Windward’s Maritime AITM technology, the vessel started to behave irregularly. With an unknown beneficial owner since 2021, the vessel changed its registered owner to a Seychelles-based company in June 2022. One month later, the vessel changed its name, call sign, and MMSI, followed by a first-time visit to Cape Verde.

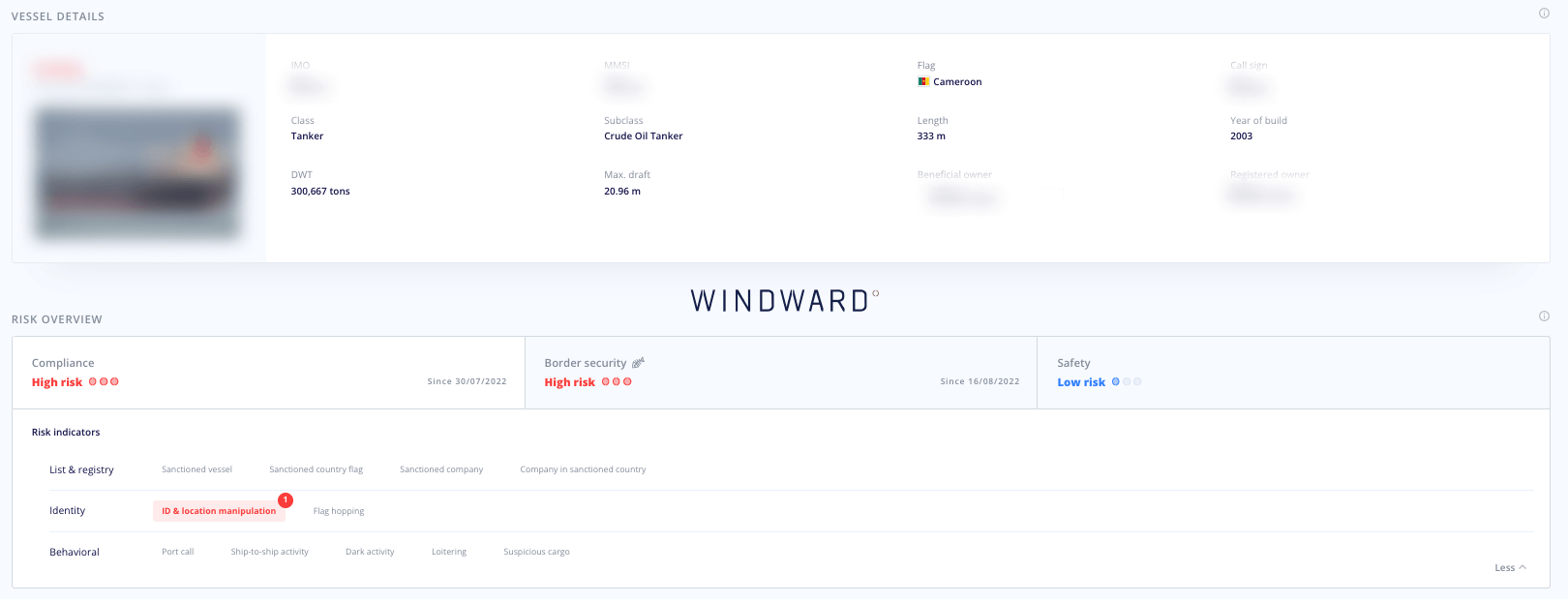

During this first-time visit to Cape Verde, the vessel did not call port and only met with a few other vessels, and anchored for a few days. About two weeks after the vessel first entered the area, it made another first-time movement toward the North Mid-Atlantic. It stayed there for three days and then continued to the South Atlantic area, where it engaged in a first GNSS manipulation event, just off the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Namibia.

Image 4: GNSS manipulation event off the Namibia EEZ

The vessel finally moved away from the area of manipulation in mid-October, only to engage in a second GNSS manipulation event within the Angola EEZ on October 21. During this second event, the tanker transmitted for six days straight from the exact same coordinate – unnatural behavior for a tanker at sea.

Image 5: Transmitting for six days straight from the same coordinates, the vessel reappeared again on October 28, 86 nautical miles from its last transmission point

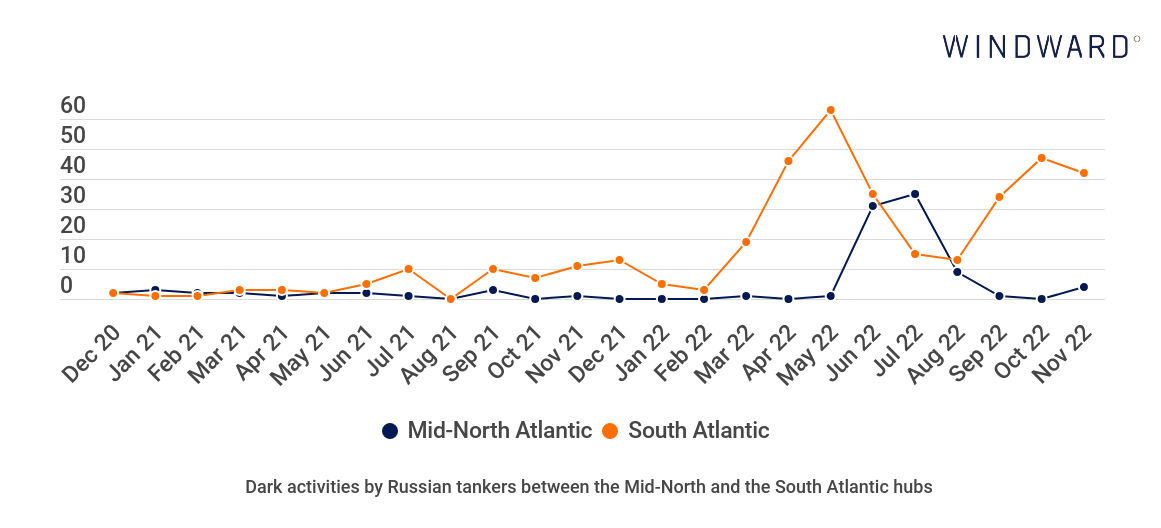

This is notable, as the Mid-North Atlantic is a known hub for dark activities and STS engagements, with vessels arriving from Russia loaded with Russian oil. Windward has also identified the beginning of a shift of the dark activities from the Mid-North Atlantic region to a more Southern area of the Atlantic. The monthly average of both dark activities and STS operations in the South Atlantic doubled in September-November 2022 compared to the monthly average of the previous three months (June-August 2022).

Image 6: Dark activities by Russian tankers

Image 6: Dark activities by Russian tankers

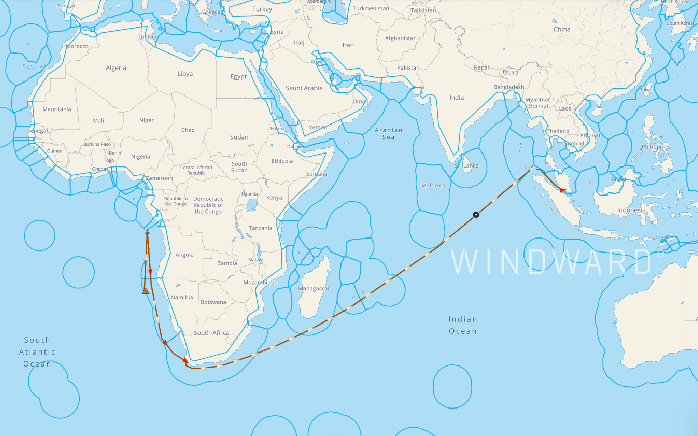

This behavioral shift is aligned with the starting point of this vessel’s GNSS manipulation. The vessel moved away from the area of manipulation seven days later, and started its journey towards Asia, following the Windward-identified path for smuggled Russian oil from the Cape of Good Hope, through the Malacca straits, to Asia. The vessel is currently sailing to its final destination, Tanjung Bruas port in Malaysia.

Image 7: The vessel sailing around the Cape of Good Hope, through the Malacca straits, on its way to Asia

Why is this noteworthy? The vessel reported a draft change from 10.0 to 20.9 on November 20 – with no official port call or STS operation to back it up. This suggests that the vessel loaded oil during its GNSS manipulation timeframe, in an area known for smuggling Russian oil.

So while this vessel was cleared for business up until its GNSS manipulation in July, and is not Russian-affiliated – it is more than reasonable to assume that it is carrying smuggled Russian oil at the time of the publication of this Windward report. Stakeholders providing services to this vessel after December 5, might not even ask for a price attestation, as there is no affiliation to Russia. This potentially exposes them to both financial and reputational risk.

Uncertainty and unanswered questions

The activities of the vessel described above highlight the ambiguities and gray areas around the implementation of the price cap. As described in the introduction of this report, there are still many unanswered questions, such as:

1. Will Russia’s political leaders and government accept the price cap, or actively work to circumvent it?

2. Will the four countries that can legally accept Russian crude oil do so? Or will they shy away to mitigate reputational damage?

3. Who is going to enforce adherence to the regulators’ set price?

4. Will Europe fold if it’s a challenging, particularly cold winter?

We do not yet know the answers to these questions. But as a trusted advisor to many throughout the maritime ecosystem, Windward will be closely monitoring the price cap implementation and using our Maritime AITM technology to discover new tactics and behavioral trends that may develop as means to disguise the origin of the regulated Russian oil.

Ben Cahill, Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, notes that the oil price cap will likely cause deceptive shipping practices (DSPs) to proliferate and will create new challenges:

“Market players manage to evade sanctions on Iranian and Venezuelan oil through ship-to-ship transfers, illicit tanker trade, and crude blending. Refiners and other buyers will probably find ways to beat the proposed requirements for trading Russian oil. They may seek letters of credit from multiple banks or use several subsidiaries to document deals at the approved price, while paying more in reality. The oil market is full of clever, rapacious people with strong incentives to bend or break rules. If the price cap is imposed, economic theory will collide with the messy reality of the market.”

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

As Ben Cahill describes it, the new price cap restrictions mark the next step in the evolution of sanctions compliance and related DSPs. Presumably, all parties are expected to undertake reasonable due diligence based on available information, but due to the many ways one can conceal the true price of the trade, price attestation alone might not be enough. As of the day of this publication, there are +1000 medium risk and +700 high risk Russian-affiliated vessels flagged in our system, and following December 5 this number is expected to increase. Screening each and every one of these is not scalable or practical when trying to run business as usual.

This article appears courtesy of maritime predictive intelligence company Windward.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.