USS McCain: Human Error Led to "Loss of Steering"

The U.S. Navy has released its final report into the two collisions involving the USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald, which led to a total of 17 fatalities and combined damages exceeding $600 million. The collision between the USS McCain and the merchant tanker Alnic MC arose in large part from a simple human error: confusion over who had control of the helm, followed by a loss of situational awareness.

Early on the morning of August 21, as the McCain entered the Strait of Singapore, she had a full bridge team of ten people, including the commanding officer (CO). However, the CO did not set a standard Sea and Anchor Detail – an additional complement of crew with specialized navigation and ship handling qualifications – in order to give the crew more time to rest. This was not in line with Navy practice for narrow or congested port approaches, and the ship's navigator, operations officer and executive officer had raised this to the CO's attention.

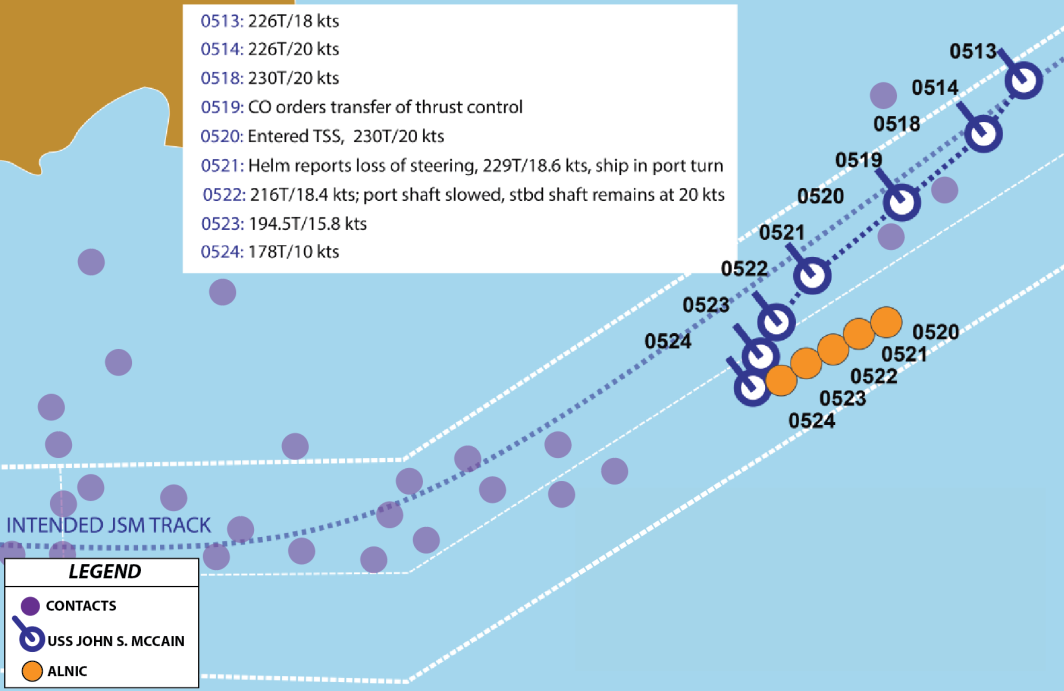

At 0519, the CO noticed that the Helmsman (one of two helmsmen on the bridge) was having trouble adjusting RPM and steering at the same time. The Helmsman was compensating for the effects of currents with between 1 - 4 degrees of right rudder to stay on course. To correct the problem, the CO ordered the officer of the deck (OOD) to split the duties of the Helmsman with the other helmsman (the Lee Helmsman). The Lee Helmsman would take over throttle control, and the Helmsman would keep control of the helm – a non-standard arrangement.

While attempting to transfer the throttle control, the watchstanders accidentally transferred steering control to the Lee Helmsman’s console and “un-ganged” the throttles (separated the port and starboard throttle controls from a coupled control to individual throttle control).

When the helm was accidentally transferred to the Lee Helm console, the Helmsman recognized that he no longer had control over the rudder, and he reported that the vessel had lost steering. The rudder defaulted to amidships, and the bridge team scrambled to find the cause.

The CO ordered the OOD to slow to 10 knots, then five. The OOD passed these orders to the Conning Officer, who ordered the Lee Helmsman to pull back.

The Lee Helmsman responded by pulling back on the throttle control for the port shaft. Since the throttles were un-ganged, this only slowed the port shaft, and with the starboard shaft still turning for 20 knots, the twin-screw vessel began to veer to port.

Three minutes later, the Aft Steering Helmsman (located at the aft control station) took control of the helm in backup manual mode. However, unbeknownst to the aft helmsman, the aft steering station already had an indicated rudder position of 33 degrees left. This pre-existing rudder command meant that when the aft station took control, the rudder swung from amidships to hard left, exacerbating the turn. Several more transfers of control occurred over the course of this evolution.

At no point did the McCain suffer a mechanical casualty leading to loss of steering or propulsion.

In the confusion that followed, no one on the bridge noticed that the McCain was crossing the bow of a nearby merchant tanker, the Alnic MC. The two ships closed rapidly and collided, just five minutes after the commanding officer's order to switch control of speed to the Lee Helmsman. Neither vessel sounded five short blasts to indicate impending risk of collision, neither attempted to make contact via VHF bridge-to-bridge communications, and the McCain's bridge crew did not sound the general alarm until after impact.

The collision damage was severe, and some crewmembers initially thought that the vessel had come under attack. The Alnic MC's bulbous bow struck the McCain's port quarter at compartments Berthing 3 and Berthing 5. Berthing 5 was a 15-foot-wide space, and the force of the impact reduced its width to five feet. It was fully flooded with a mixture of fuel and water in less than a minute.

Two sailors out of the 12 who were in Berthing 5 managed to escape; the remaining 10 crewmembers did not survive. 48 others throughout the ship sustained injuries requiring medical treatment, and five were so severely injured that they could not return to duty within 24 hours.

The Navy found that the McCain collision was avoidable, and that training, seamanship and command culture deficiencies were largely to blame:

- If the CO had set Sea and Anchor Detail adequately in advance of entering the Singapore Strait Traffic Separation Scheme, then it is unlikely that a collision would have occurred.

- Multiple bridge watchstanders lacked a basic level of knowledge on the steering control system, in particular the transfer of steering and thrust control between stations.

- The CO ordered an unplanned shift of thrust control from the Helm Station to the Lee Helm station, an abnormal operating condition, without clear notification.

- Senior officers and bridge watchstanders did not question the helm’s report of a loss of steering nor pursue the issue for resolution.

- If McCain had sounded at five short blasts or made bridge-to-bridge VHF hails, then it is possible that a collision might not have occurred.

- Personnel assigned to ensure bridge watchstanders were trained had an insufficient level of knowledge to maintain rigor in the qualification program. The senior-most officer responsible for these training standards lacked a general understanding of the procedure for transferring steering control between consoles.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The report also identified systemic factors, including broader issues with training deficiencies and excessive workloads. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said that the Navy is committed to fixing these problems. “We must never allow an accident like this to take the lives of such magnificent young Sailors and inflict such painful grief on their families and the nation,” Richardson said in a statement. “We must do better.”

A PDF of the Navy’s final report is available here.