U.S. Navy Celebrates 60th Anniversary of Deepest Ocean Dive

The National Museum of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C., has celebrated the 60th anniversary of the Navy's deepest ocean dive in the bathyscaphe Trieste.

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) purchased Trieste for scientific observations, and the record dive reached approximately 36,000 feet below sea level on January 23, 1960.

U.S. Navy Lt. Don Walsh conducted the dive with Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard, and Walsh recalled the experience at the celebration ceremony:

Plunging into the abyss of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, the men heard a loud cracking sound. Already 30,000 feet below sea level, they faced the ultimate decision - risk their lives to become the first people to travel to the deepest part of the ocean, the Challenger Deep, or return to safety.

The crack had scarred one of Trieste’s outer plexiglass panels. Walsh and Piccard (whose father designed Trieste) decided to push on. After all, if Trieste had suffered catastrophic damage, both men would already be crushed by the ocean’s pressure. After a nearly five-hour descent, the Trieste reached the bottom of Challenger Deep.

Because it was necessary to complete the journey in a single day, when there was daylight available, Walsh and Piccard could only spend 20 minutes in the Challenger Deep before heading back to the surface. The men didn't see much when they hit bottom. A large cloud of particles from the sea floor engulfed the ship, preventing the pilots from making further observations.

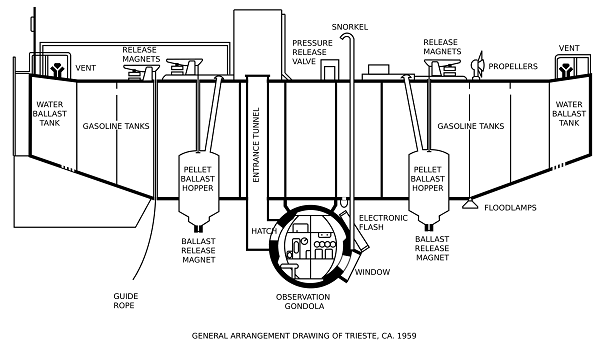

Bought by ONR in 1958, Trieste was designed to go deeper than any craft before it. The ship boasted a small, spherical crew space slung underneath a large float resembling a balloon in both shape and function.

Walsh attended the U.S. Naval Academy and became a submariner. Not long into his naval career, the Navy needed volunteer pilots to test Trieste. However, since bathyscaphes didn’t operate like traditional ships, volunteers were scarce.

Trieste had to be towed to an area for exploration, and it sank to its desired depth. To ascend, it simply dropped ballast and rose to the surface. Walsh said few people in the Navy wanted to risk their lives sitting in a steel ball the size of a refrigerator while descending thousands of feet.

“This was a balloon, plain and simple, except in the water,” said Walsh, who retired from the Navy as a captain. “I had nothing to lose. I was on the ‘junior varsity’ for the Navy. My class standing at the Naval Academy was not great. I was told, ‘You’re officially stupid.’”

Adm. Arleigh Burke, then chief of naval operations, told Walsh if he and Piccard were successful, the Navy would publicly celebrate the mission, but, if they failed, it would remain silent.

Worried about the potential dangers of the Mariana Trench, a risk-averse commanding officer ordered Trieste’s crew to abort the journey on launch day. However, a chief petty officer decided to deliver a delayed response to the commanding officer only after Trieste was 10,000 feet down, knowing it would be too late to stop the trip.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The record dive ushered in a golden age of manned underwater exploration in the 1960s and 1970s, in which submersibles helped make extraordinary discoveries in biology, geology, chemistry, oceanography and other fields.