To Save the Sounion, Ambrey Combined Salvage With Security and Politics

In a movie pitch made real, the group had to tow a burning tanker under pressure from terrorists, military forces and governments

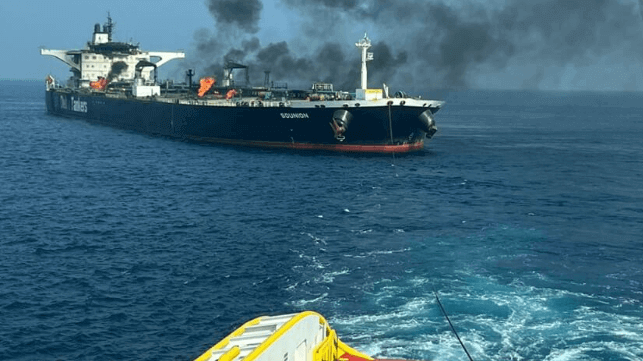

Maritime security firm Ambrey has released the first detailed recounting of the operation to save the tanker Sounion, which was attacked and burned by Houthi forces last fall. In Ambrey's recounting, it may rank among the most challenging salvage operations since the Costa Concordia or the Deepwater Horizon, with the unique risk of operating next to a hostile armed militia.

The Greek-owned tanker Sounion was attacked by Houthi forces three times on August 21, disabling the engine and leaving the ship adrift. After withstanding small arms fire, a possible shoulder-launched grenade, multiple projectiles, and a (thwarted) suicide drone boat attack, the crew of the Sounion asked for help abandoning ship. On August 22, a French frigate carried them to safety.

The next day, Houthi fighters boarded the tanker to plant explosive charges on the main deck and in the wheelhouse. The blasts tore multiple holes in the tanks, igniting more than a dozen fires, which continued to burn while the owners and insurers looked for salvage options.

????? ?????? ?????? ??????? ??????? ??????? ????????? SOUNION ?? ????? ?????? ????? ???? ?????? ??????? ??? ??????? ???? ??? ?????? ??? ????? ?????? ???????. pic.twitter.com/nvjHU4SFG2

— ?????? ???? ???? (@army21ye) August 23, 2024

Ambrey - which had already been engaged to provide security during the voyage - accepted the high-risk job. The Sounion salvage presented unique factors perhaps never seen before in combination, including multiple active cargo fires on a laden supertanker; ongoing risk of attack or hijacking by a well-equipped terrorist force; a high level of political interest and multi-government involvement; and a severe risk of harm to regional food security and economic activity in the event of a spill.

Sounion was located just 60 miles off the coast of Yemen, well within range of Houthi drone and missile capabilities, and she was under continued surveillance by Houthi vessels. In addition to the serious security situation, the tanker and her 160,000-tonne cargo of oil were adrift and burning, threatening to leak, sink, or run aground - any of which could result in a spill up to four times the size of the Exxon Valdez. The clock was ticking.

Courtesy EUNAVFOR Aspides

Courtesy EUNAVFOR Aspides

Ambrey decided that it would not be advisable to carry out a major marine firefighting and salvage operation within reach of Houthi military capabilities, since the group had already attacked the tanker several times. To conduct the salvage, it would be necessary to tow the Sounion while she was still on fire - a task for which there were few precedents or guidelines.

The southern Red Sea has limited local salvage and heavy towage assets, so Ambrey moved to mobilize people and equipment to the area as fast as possible. The Greek-owned salvage tug Aigaion Pelagos would be the lead towing vessel, with a second tug to assist as needed. Government involvement at a high level helped smooth the way for transfer of equipment through customs on an expedited basis.

The operation began in earnest around September 2, but halted September 3 because the response group "concluded that the conditions were not met to conduct the towing operation," the EUNAVFOR security mission reported at the time. It would be mid-September before the team was assembled, all technical details ironed out, and a European naval escort group mobilized provide security. The tow began September 13, three weeks after the ship began burning.

In conversation with Lloyd's List, Ambrey's Joshua Hutchinson explained that the most significant issue with the tow was the political "port of refuge" dilemma. Reducing risk required a safe anchorage, but no coastal state wanted to take the risk of allowing the Sounion nearby. The salvage team needed to tow the vessel north, but Saudi forces did not want to allow the burning tanker near Saudi shores for fear of a spill. It took high-level diplomatic contacts to smooth the disagreement out and secure permission for the transit.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Marine firefighting operations at night aboard the Sounion (JMIC)

On October 9, after three weeks of firefighting, the blazes were out and the holes in the cargo tanks had temporary patches installed. Towing resumed, and at Suez, the process of a slow and careful STS transfer began to remove her oil. The lightering operation ended at last on December 2, and the project began to come to an end - unlike Houthi attacks, which continue over the Red Sea.