Record-Setting Dive Finds Wreck of Famed WWII Destroyer USS Johnston

A privately-funded expedition has explored the main wreck site of the storied destroyer USS Johnston, the deepest known shipwreck in the world at about 21,000 feet under the sea.

The funder of the expedition, Victor Vescovo, is a former US Navy commancder who piloted his submersible, DSV Limiting Factor, to the wreck in two separate eight-hour dives. According to expedition operator Caladan Oceanic, they were the deepest wreck dives (manned or unmanned) in history.

The USS Johnston was a U.S. Navy Fletcher-class destroyer that sank in the Battle off Samar on October 25, 1944. Armed with nothing more than her torpedoes and five-inch guns, Johnston played a key role in defending a flotilla of escort carriers from a vastly superior force of Japanese cruisers and battleships, led by the flagship "super-battleship" Yamato.

The massive Japanese force lost three heavy cruisers in the engagement against the lightly-armed U.S. Navy task force. Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita - fooled by the ferocity of the Americans' rearguard action - withdrew and returned to Japan. The battle marked the end of the Imperial Japanese surface fleet's capability as an effective fighting force for the remainder of the war.

USS Johnston in Seattle, 1943 (Naval History and Heritage Command)

U.S. Navy destroyers laying a smoke screen under Japanese fire during the Battle off Samar (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Escort carrier USS Gambier Bay making smoke and taking fire in the Battle off Samar. USS Johnston's commander ordered his crew to attack a far larger Japanese force, hoping to draw fire away from Gambier Bay and five other slow-moving escort carriers. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

“In no engagement in its entire history has the United States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in the two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar,” wrote Rear Admiral Samuel E. Morison in his History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II.

Upon the commissioning of USS Johnston, commanding officer Cmdr. Ernest Evans told his crew that he would “never run from a fight,” and that “anyone who did not want to go in harm’s way, had better get off now.” The crew stayed aboard until the vessel was shot out from under them, and only 141 out of her 327 crewmembers were rescued. Commander Evans was not among the survivors; he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, making him the first Native American in the U.S. Navy to receive the nation's highest military award. USS Johnston was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, the United States' highest unit award.

The wreck of the Johnston was discovered in 2019 by the late Paul Allen’s vessel R/V Petrel, under the leadership of ocean wreck explorer Robert Kraft. On that expedition, pieces of the vessel were identified by a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV), but the majority of the wreck lay deeper than the ROV’s rated depth limit of approximately 20,000 feet.

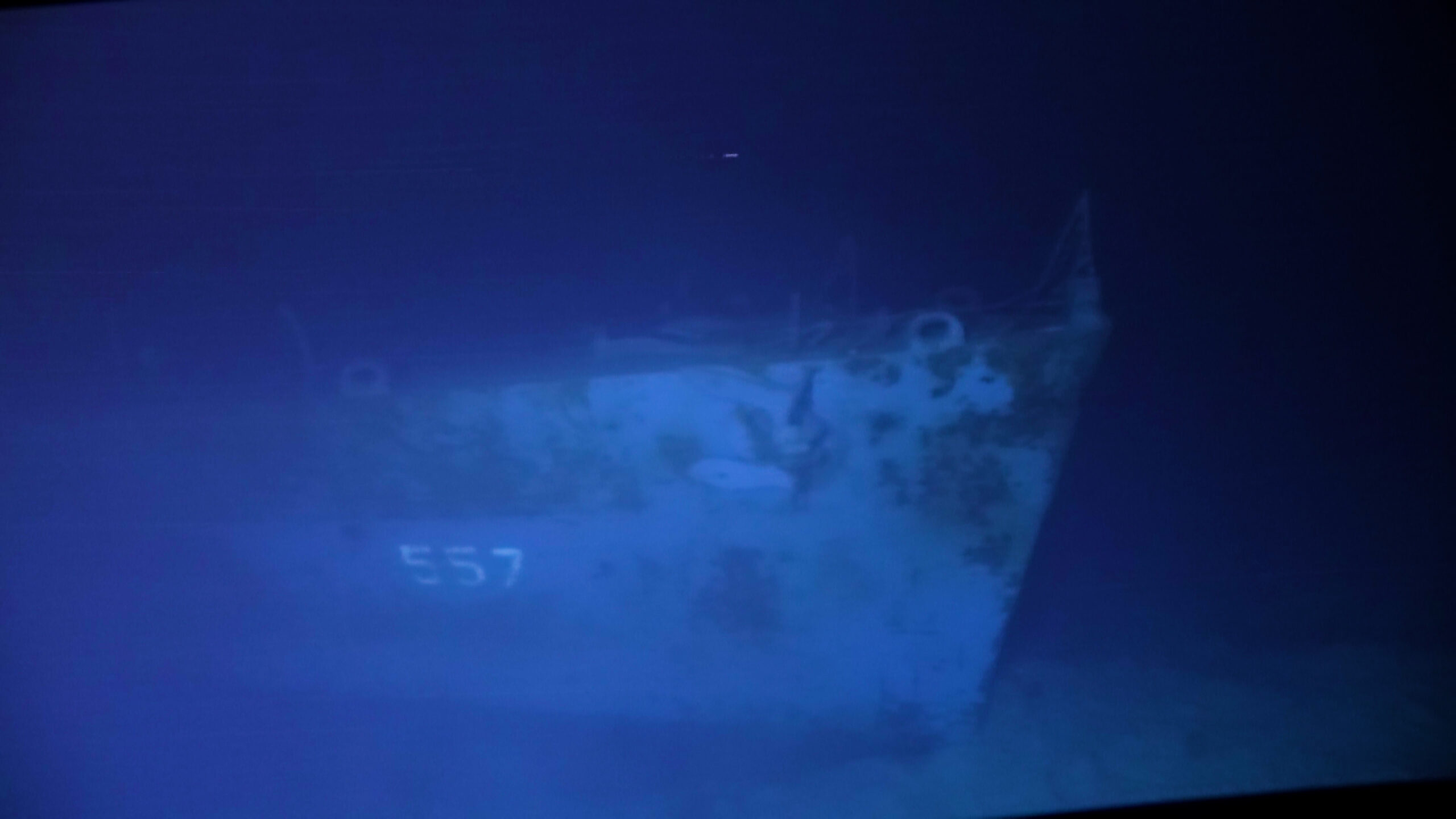

Vescovo's recent dives found the front two-thirds of the vessel largely intact. The destroyer's hull number “557” is clearly visible on both sides of its bow, and two full five inch gun turrets, twin torpedo racks, and multiple gun mounts are still in place on the superstructure. According to Caladan Oceanic, no human remains or clothing were seen at any point during the dives, and nothing was taken from the wreck.

USS Johnston's bow (Caladan Oceanic)

Extensive research by naval historian Lt. Cmdr. Parks Stephenson (USN, ret'd) allowed the position of the wreck to be plotted during the development of a dive plan. “Reading the accounts of the Johnston’s last day are humbling and need to be preserved as upholding the highest traditions of the Navy. This was mortal combat against incredible odds," said Stephenson. "[During the dive] we could see the extent of the wreckage and the severe damage inflicted during the intense battle on the surface. [Johnston] took fire from the largest warship ever constructed - the Imperial Japanese Navy battleship Yamato - and ferociously fought back. All of the accounts pay tribute to the crew’s bravery and complete lack of hesitation in taking the fight to the enemy, and the wreckage serves to prove that."

Wreck of USS Johnston, showing obvious signs of battle damage (Caladan Oceanic)

The sonar data, imagery and field notes collected by the expedition will not to be made public. Instead, the materials will be provided to the U.S. Navy for dissemination as it deems appropriate, Caladan Oceanic said.

“The wreck of Johnston is a hallowed site,” said Rear Admiral Samuel Cox, head of the U.S. Navy's History and Heritage Command. “I deeply appreciate that Commander Vescovo and his team exhibited such great care and respect during the survey of the ship, the last resting place of her valiant crew. Three other heroic ships lost in that desperate battle have yet to be found.”

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

At the conclusion of the expedition, the crew of the research vessel DSSV Pressure Drop came to a stop, sounded the ship’s whistle, and laid a wreath on the oceanic battlefield.

“In some ways we have come full circle. The Johnston and our own ship were built in the same shipyard, and both served in the US Navy. As a U.S. Navy officer, I’m proud to have helped bring clarity and closure to the Johnston, its crew, and the families of those who fell there," Vescovo said.