NOAA Warns of Risks in a Warming Arctic

In the 2019 edition of its annual Arctic Report Card, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration warns of rapid changes driven by warming in the far north - including changes to the Bering Sea fisheries that provide 40 percent of the annual U.S catch. Arctic and subarctic fish species are shifting to the north, a phenomenon corresponding to a loss of sea ice and warming bottom temperatures.

Since 1980, surface air temperatures have risen throughout the Arctic. The annually-averaged land based surface air temperature from October 2018 through September 2019 was the second-highest on record (the highest was in 2016). Every year since 2014, the average has exceeded that experienced between 1900 - when recordkeeping began - and 2013.

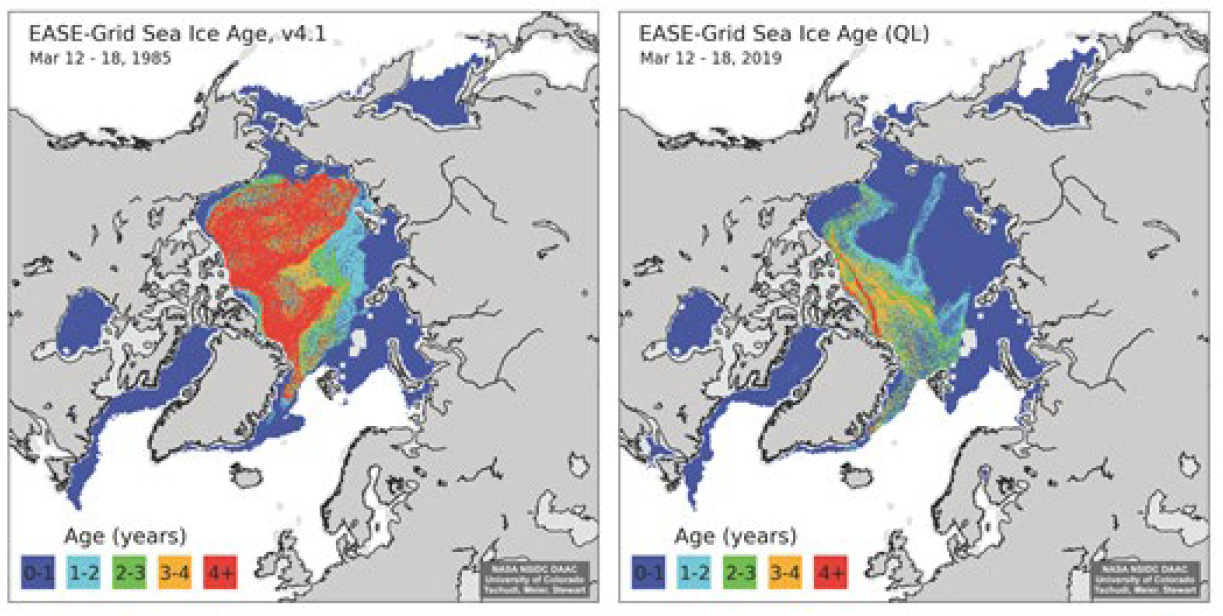

That warming parallels the loss of Arctic sea ice cover. The end-of-summer minimum extent this September was tied for second-lowest (along with 2007 and 2016) in the 41-year satellite record. It is also getting thinner. Old ice of four years or more now makes up just one percent of the coverage, down from 33 percent in 1985. Thinner, more fragile first-year ice now makes up more than three-quarters of the total.

Late-winter Arctic sea ice (not annual minimum extent) differentiated by age range, 1985 (left) and 2019 (right)

Less ice means more open water, and open water absorbs more solar radiation, meaning more ocean warming. This also means more ocean primary productivity - the rate of growth of phytoplankton, the base of the marine food web. Over the past 15 years, primary productivity has risen in all regions of the Arctic Ocean, particularly in the Eurasian Arctic and the Barents and Greenland Seas.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

However, the same warming has implications for the Bering Shelf, the most productive fishery in the world. Maximum southern sea ice extent in the Bering hit record low values in 2019 and 2018, with both years about 30 percent below the long-term average. The record low sea ice disrupted the formation of the normal cold bottom water temperatures on the shelf, leading to changes in marine life distribution. In 2018, there was a large northward shift in the distribution of walleye pollock and Pacific cod, two commercially-important species in the Bering. (Further south, in the Gulf of Alaska, the Pacific cod stock has declined far enough that the federal government is closing the fishery altogether for 2020 in hopes of its recovery; NOAA pins the responsibility for the Gulf cod population's decline on warming waters.)

In Greenland, warming has led to accelerated ice mass loss from the island's massive glaciers, and the rate is currently estimated in the range of 254-267 billion tons per year. The scientific consensus on the loss rate is high enough that Greenland is now expected to contribute about half a foot to global sea level rise by 2100, a higher amount than previously thought.