USS Fitzgerald Collision: High Speed, No AIS, Heavy Traffic

The U.S. Navy has released its final public report on the two collisions involving the USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain, including previously unreleased details of the events leading up to the accidents. The Fitzgerald timeline appears to show a series of decisions and oversights that put her in close quarters situations more than once on the night of her encounter with the ACX Crystal – often without notification to her commanding officer, as required by standing orders.

At 1630 hours on June 16, the USS Fitzgerald got under way from Yokosuka, Japan, making a course southbound for sea. At 2300 hours, her commanding officer, executive officer and navigator left the bridge, leaving the officer of the deck with the conn.

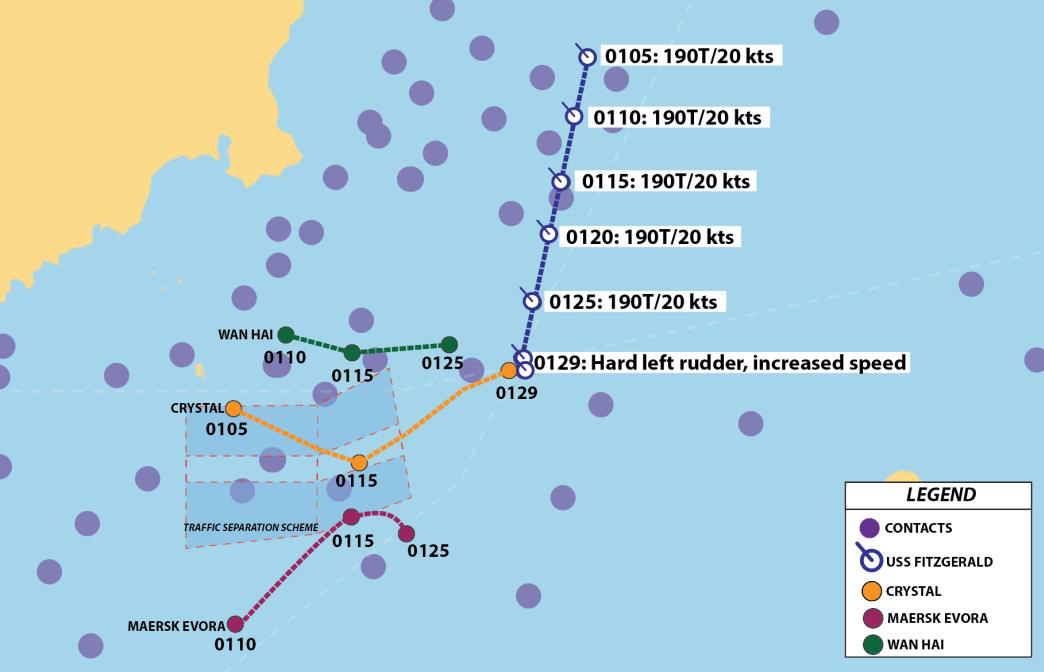

Fitzgerald approached the vessel traffic separation (VTS) scheme north of Oshima Island and came to a course of 190 at 20 knots. Her pre-approved navigation track did not account for or follow the area’s VTS patterns, she was not broadcasting an AIS signal and all her exterior lights were extinguished (except for navigation lights).

At 0108, Fitzgerald crossed the bow of a ship at approximately 650 yards, passed a second vessel at two nm and a third vessel at 2.5 nm. In contravention of standing orders, no reports of these three encounters were made to the commanding officer.

At 0110, Fitzgerald's watchstanders noted the radar signature of the container ship ACX Crystal at 11 nm, and they attempted to initiate a radar track on her, without success. At 0117, the OOD plotted a track on a vessel that he believed to be the Crystal, and determined that the contact would pass at 1500 yards on the starboard side.

At 0120, the junior officer of the deck visually sighted Crystal and noted that her course would coincide with Fitzgerald's track. The OOD remained convinced that Crystal would pass at a safe distance, even after the junior officer advised him to slow down. Two other ships – the Wan Hai and Maersk Evora – were also approaching with close CPAs, and there were over a dozen other contacts in the vicinity.

At 0127, with the Crystal closing fast, the OOD ordered a fifty degree turn to starboard, then rescinded the command and ordered full speed ahead and hard to port. The actions were delayed as the Conning Officer “froze” in the moment. The OOD and the Conning Officer both began to shout orders to the helm.

At 0129, two minutes and 1,200 yards of forward travel later, the Boatswain’s Mate of the Watch put the rudder over hard left and pushed the ship’s throttles forward.

At 0130:34, the Crystal struck the Fitzgerald amidships on the starboard side, crushing the commanding officer's cabin and creating a 12-foot by 17-foot hole below the waterline, leading to rapid flooding in a machinery space and a berthing area (below left).

At no point did the bridge watchstanders on Crystal or Fitzgerald make radio contact. In addition, Fitzgerald's watchstanders did not sound the general alarm to warn their shipmates of an impending collision.

At no point did the bridge watchstanders on Crystal or Fitzgerald make radio contact. In addition, Fitzgerald's watchstanders did not sound the general alarm to warn their shipmates of an impending collision.

In the aftermath, seven sailors drowned in the rapid flooding of Berthing 2, three were injured, and the survivors worked heroically to save their ship. Fitzgerald's commanding officer, executive officer, master chief, and several of her watchstanders have been relieved of duty. Fitzgerald herself will be out of commission for an extended repair period in Pascagoula, Mississippi.

The Navy concluded that the Fitzgerald collision was avoidable. Specifically, she appears to have violated COLREGS in several ways:

- She was not operated at a safe speed appropriate to the number of other ships in the immediate vicinity.

- She failed to maneuver early as required with risk of collision present.

- She failed to notify other ships of danger and to take proper action in extremis.

- Watchstanders performing physical look out duties did so only on Fitzgerald's left (port) side, not on the right (starboard) side where the three ships were present with risk of collision.

In addition:

- Watch team members responsible for radar operations failed to properly tune and adjust radars to maintain an accurate picture of other ships in the area.

- Supervisors responsible for maintaining the navigation track and position of other ships

were unaware of existing traffic separation schemes and the expected flow of traffic, and did not utilize the Automated Identification System to gather information on nearby vessel traffic.

- Her approved navigation track did not account for, nor follow, the Vessel Traffic Separation Schemes in the area.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The report also identified systemic factors, including issues with training deficiencies and excessive workloads. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said that the Navy is committed to fixing these problems. “We must never allow an accident like this to take the lives of such magnificent young Sailors and inflict such painful grief on their families and the nation,” Richardson said in a statement. “We must do better.”

A PDF of the Navy’s final report is available here.