Enforcing the Rule of Law: The Royal Navy's West African Patrol

For 55 years, the Royal Navy patrolled the Gulf of Guinea to suppress a brutal maritime crime.

Last week, the crew of the icebreaker HMS Protector paid their respects to the thousands of Royal Navy sailors who helped put an end to the West African slave trade. They joined leaders of the island of St. Helena in a service of remembrance and thanks for the men of the West Africa Squadron – and the tens of thousands of slaves they liberated.

For more than half a century, the tiny island of St. Helena was the hub of the fight against slavers in the transatlantic trade. The UK ended its own legalized transatlantic slave exports with the Slave Trade Act of 1807, and the new law empowered Royal Navy warships to board British-flagged vessels to conduct enforcement actions. (The institution of legalized slavery continued in British-controlled colonies until 1833, but without a legal source of newly-imported manpower.)

Under the Act, if the Royal Navy found slaves on board a vessel off Africa, it could impose a fine of £100 per enslaved person, payable by the captain. The vessel and all of its fittings would also be seized (and often pressed into service as a new patrol ship). A series of treaties with other European powers gradually expanded the number of slave ships that the Royal Navy could board, and the British created a system of admiralty courts in West African ports to administer punishment.

The challenges that the West Africa Squadron faced were stark: just a handful of small Royal Navy sailing ships had 3,000 miles of West African coastline to monitor, and they were up against armed, motivated and unscrupulous slavers. Often enough, interdictions would turn into naval battles. Among the losses was the ten-gun sloop HMS Waterwitch, which spent 21 years hunting down slave ships until one sank her in 1861.

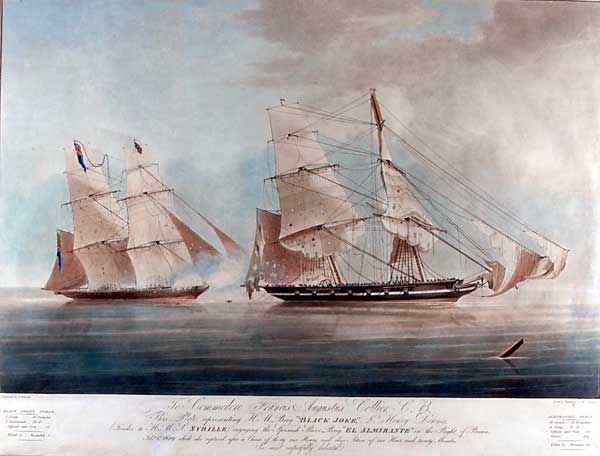

The captured slave ship-turned-warship HMS Black Joke attacks the Spanish slave ship El Almirante off West Africa (Nicholas Matthews Condy)

The cost to the Royal Navy was heavy: tropical diseases like malaria and yellow fever exacted a terrible toll on servicemembers, and about 1,600 British sailors died over the course of the five-decade campaign. It was also incredibly costly from a financial standpoint, absorbing up to half of the UK's naval budget and up to two percent of all government expenditures at its peak.

From 1808 to 1863, the squadron seized about 1,600 ships and rescued an estimated 150,000-200,000 people from slavery. Though this represented just a tiny fraction of the estimated 3.2 million West Africans who were captured, enslaved and exported for profit over the same period, it was by far the most significant human-rights action at sea during the 19th century.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

In the latter days of the campaign, the Royal Navy enforcement action expanded into Brazilian territorial waters and took a particularly aggressive turn, including forays into Brazilian harbors. That action was credited with helping to extinguish the last remnants of Brazil's transatlantic slave trade, which lasted longer and accounted for greater volume than that of any other nation.

The rescued slaves became the property of the Crown, and for legal purposes they were treated as a prize of war. Though the law forbade reselling them to any third party, British admiralty courts were empowered to enlist the rescuees in "His Majesty's Land or Sea Service, as Soldiers, Seamen, or Marines, or to bind the same, or any of them, whether of full Age or not, as Apprentices, for any Term not exceeding Fourteen Years." However, most were freed and delivered to British colonies like St. Helena and Sierra Leone, where they would be safe from recapture by slavers. The city of Freetown, Sierra Leone takes its name from these new arrivals; many would go on to volunteer to fight for the British Empire in the West India Regiment.